|

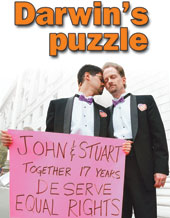

It?s a puzzle that has baffled biologists for years: how has homosexuality survived evolution? Homosexual relationships don?t yield children. From a purely reproductive perspective, being gay is a disadvantage. The laws of evolution outlined by Charles Darwin 145 years ago dictate that any genes involved in homosexuality should have been wiped out long ago. But the trait has endured, throwing up what biologists have dubbed a ?Darwinian Paradox?.

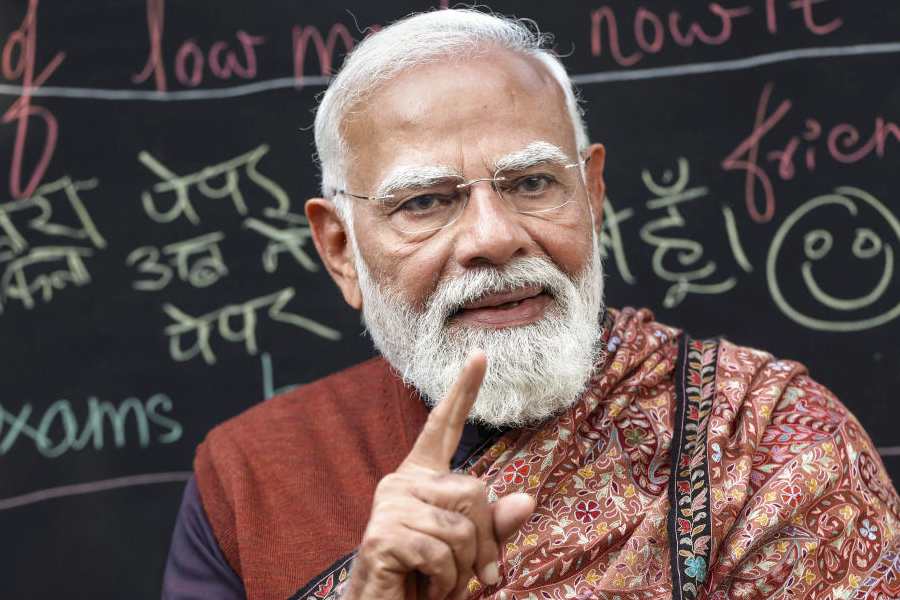

Now an Italian scientist, who began his studies of primate behaviour 25 years ago in India, watching rhesus monkeys near Shimla, may have solved the paradox of homosexuality. Evolution and human behaviour scientist Andrea Camperio-Ciani has found a biological explanation for how genes that might influence homosexuality have moved down the centuries, generation after generation, despite not contributing to the birth of children for most homosexual men.

The study by Camperio-Ciani suggests that a set of genes that may partly explain homosexuality in men may also drive women to seek more sex with men. ?They may be described as a set of genes that influences attraction to males,? says Camperio-Ciani, a senior physical anthropologist at the University of Padova, Italy. ?A man with these genes could become homosexual while women who have these genes might be more attracted to men.?

These women are likely to have more children which would explain how the genes are passed down the generations. Camperio-Ciani and his colleagues have emphasised that genetic factors in their study accounted for just one-fifth of the gay men.

The landmark study, published last month in the Proceedings of the Royal Society, is the first ever to suggest a solution to the Darwinian paradox based on real data from gay men and their families. The research by Camperio-Ciani and his colleagues also bolsters support for a biological basis for sexual orientation in humans and hints at the existence of ?hitherto-unsuspected? reproductive advantages associated with homosexuality.

Camperio-Ciani asked 98 homosexual men and 100 heterosexual men in northern Italy to answer a questionnaire that sought details of their family trees and the sexual orientation of their siblings, cousins, parents, aunts and uncles. The study covering 4,600 people in all found that female maternal relatives of gay men had a higher fecundity ? a greater potential to produce children ? than female maternal relatives of heterosexuals.

This finding can be explained through a set of genes that promotes sexual attraction to men, says Dr Simon LeVay, a neuroscientist and author in the US who began exploring links between biology and sexual orientation in the early 1990s. The genes may be capable of ?causing homosexuality in men and hyper-heterosexuality in women,? says LeVay.

Maligned and misunderstood for long, homosexuality has largely evoked responses dictated by cultural, social, political and moral sentiments. It was considered ?unnatural? behaviour and was once even viewed as a psychiatric disorder. It was only in 1986 that the American Psychiatric Association deleted references to homosexuality from its diagnostic manual for mental disorders. The exact prevalence of homosexuality remains unknown. Surveys are considered unreliable, but indicate that its prevalence may range anywhere from 0.05 per cent to 9 per cent of any population, depending on how and where the survey is conducted.

While homosexuality is now increasingly viewed as a natural variation in sexual orientation, the evidence for a biological basis for sexual preferences has grown.

Neuroscientist LeVay was at the Salk Institute in California in 1991 when he discovered subtle differences between the brains of homosexual and heterosexual men. By examining the brain tissues of dead homosexual men, heterosexual men, and women, he found that a cluster of cells in the brain known to be involved in male sexual behaviour was twice as large in heterosexual men as it was in homosexual men.

Two years later, biologist Dean Hamer at the US National Institutes of Health found an elevated rate of homosexuality in the maternal line of homosexuals. Hamer, who?s been studying the role of inheritance in human behaviour, personality traits, and cancer risk-related behaviour such as cigarette smoking, used the finding to suggest that genetic factors on the X-chromosome favour male homosexuality.

In the mid-1990s, a study by Ray Blanchard, a psychiatrist at the University of Toronto, suggested that sexual orientation of an individual was affected by the number of older brothers ? each additional older brother increases the odds of homosexuality by 33 per cent.

This may be explained through what biologists call a maternal immunity reaction. The first male foetus may trigger an immune reaction in the mother. During a subsequent pregnancy involving a male foetus, this immune reaction may alter the course of foetal brain development, which in turn may influence sexual preferences later in life.

The new study by Camperio-Ciani has confirmed the previous findings that homosexuals have more maternal than paternal male homosexual relatives, that homosexual males are more often later-born than first-born, and that they have more older brothers than older sisters. It thus bolsters evidence for the suggestion that genetic factors on the X-chromosome may influence homosexuality and that when mothers have many sons, the younger sons are increasingly likely to be homosexual. ?This study shows that there is an unquestionable genetic component to homosexuality,? says Dr B.K. Thelma, a geneticist at the University of Delhi.

|

| Hidden agenda: Where in the DNA are the genes for sex? |

The Italian study has showed that the mothers of gay men had an average of 2.7 babies, while those of heterosexual men had 2.3 babies. The corresponding figure for the maternal aunts of gay men was 1.9, while the maternal aunts of straight men had an average count of 1.5. Camperio-Ciani admits that his data is based on a small sample. ?But from the small sample that we have it appears that the mothers and aunts of homosexual men had either a lower number of abortions and medical problems during pregnancy or appeared less concerned about using contraception,? he adds.

He says that the idea that a set of ?double-action? genes accounting for male homosexuality as well as enhanced fecundity in women came from Giorgia, his 15-year-old school-going daughter. They were driving to the seaside two years ago and he was talking to her about the data he had extracted through the questionnaires. ?It was she who first suggested to me that the same set of genes might have different actions in different genders,? Camperio-Ciani told KnowHOW in a telephone interview from Thailand, where he is currently on a research field trip, last week.

However, some biologists caution that the concept of genes that increase attraction to males is still highly speculative. ?The fecundity in the maternal line of homosexuals might have either physiological or behavioural components,? says Prof. Sundaram Doraiswamy who teaches evolutionary biology at the University of Delhi. ?The components of fecundity need to be analysed to determine whether it truly emerges from behaviour.?

While the new study points to genetic factors influencing sexual orientation, Camperio-Ciani warns that the concept of prenatal screening for homosexuality would be ?impossible and a stupid thing to do?. The findings show that there is no single gay gene, but multiple genes that merely influence sexual orientation. They do not automatically guarantee homosexuality.

Camperio-Ciani says the study, in fact, also highlights the importance of individual experiences. In their sample, just 21 per cent of male homosexuals could be accounted for through the maternal immunity or excess homosexual relatives on the maternal side ? 79 per cent of the homosexuals remained unexplained.

Researchers concede that cultural and social aspects of sexual orientation cannot be denied. ?For example, there seems to be a kind of male homosexuality ? mostly directed toward male teenagers ? that occurs in societies where unmarried men have little or no access to women,? says LeVay. ?Most researchers would agree that sexual orientation is more fluid and more responsive to social circumstances in women than in men.?

Psychologists caution that while there exist many myths, there is no hard scientific evidence pointing to any specific experiences that can lead to homosexuality. One prevalent myth suggests that if children are brought up in a certain way, it can lead to homosexuality; another says that women who?ve had a bad sexual experience with men tend to become lesbians. ?No such cause-effect relationship has been established for homosexuality, or for heterosexuality,? says Radhika Chandiramani, a clinical psychologist in New Delhi.

Geneticists say that there are other examples of multiple gene conditions in which ?environmental factors? determine the outcome in ways still unknown. Schizophrenia, for instance, is a multiple gene condition but its ?causes? remain undetermined. Twins, says University of Delhi geneticist Thelma, share the same genes and the same prenatal uterine environment, but there are cases where one twin has schizophrenia and the other doesn?t.

Camperio-Ciani may have solved Darwin?s paradox, but the scientific pursuit for an understanding of sexual orientation is far from over.