A strange cluelessness has become the defining feature of our political discussions. The opponents of the ruling regime, who are expected to function as vigilant and constructive observers, are confused and pessimistic. Their criticisms tend to revolve around a particular political move or a policy proposal introduced by the government. There is no enthusiasm for reshaping the political discourse by offering any constructive package of ideas. This negative, one-sided, and ineffectual style of opposition politics does not have any space for accommodating the hopes and the aspirations of people and communities.

There is another mode in which this despairing attitude finds a political expression. A section of pro-regime commentators wants us to believe that the mistakes of the past are being corrected, slowly and gradually, and the ultimate future is about to arrive. In this schema, there is an elusive and endless search for bad guys, bad times, and bad decisions in history to redefine the present as an age of political justice. The future, hence, can only be envisaged as a residue of a reconstituted past. This seemingly passionate mode of thinking is also inward-looking in nature wherein hope and aspiration can only be understood as hurt sentiments.

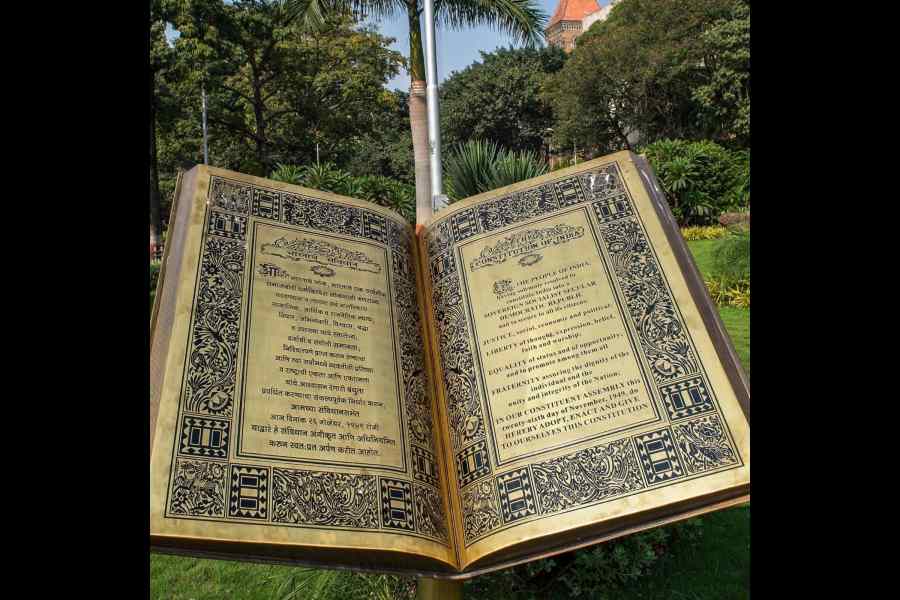

Despite this overtly negative character of our political discourse, the election-centric imagination of democracy is thriving in an unprecedented manner. The Constitution has been recognised as the most sacred political document and democracy has become an end in itself. Does it reflect a contradiction? Is there any correlation between the pessimism of the political discourse and the vibrancy of political action?

To explore these issues, we must first look at the nature of our election-centric democracy. Political parties are enthusiastic about participating in the electoral arena. In fact, elections have been transformed into an industry where political parties compete as individual firms. They treat voters as consumers, prepare appealing policy packages (including freebies) to attract them, and set out a favourable political equilibrium. In this process, the voter-choices are studied with great care for the purposes of mobilisation. At the same time, serious attempts are also made to create new political issues and needs. This professionalisation of politics has produced two related outcomes.

First, the political class (which includes all political players and groups) has acquired a monopoly when it comes to defining the issues and the concerns for electoral competition. This unwritten consensus has become so powerful that the problems of everyday life — ever-growing unemployment, economic disparity, and price rise — which are always highlighted by voters as fundamental reasons to take part in political processes, do not become electoral issues.

Second, the actual transformation of voters into rational consumers has encouraged the political class to maintain a strategic distance from the social world. The social is seen as an autonomous sphere where the forces of caste, class and religion create a workable equilibrium to sustain a tactical balance of power. The political class does not want to destabilise the structural configuration of the social sphere. Instead, it employs societal divisions — caste, religion, language — to make winnable electoral formations at the constituency level.

The social and the electoral, thus, continue to reproduce each other in an interesting manner. This ‘business as usual’ attitude does not merely legitimise the existing framework of power but also encourages the political parties to keep away from societal conflicts (unless they do not have any electoral value). The idea of social change through politics, hence, becomes completely meaningless. This is one of the main reasons why the political discourse in India has become strikingly dark

and depressing.

This brings us to a critical question: why do we need to recognise politics of hope as a legitimate expectation? After all, the political class has worked out a few acceptable norms to run the system and despite several minor and major interruptions (including the national Emergency of 1975-77), it has been functioning smoothly so far for over seven decades. Here we must go back to the Constitution — not merely as a legal text but as a political doctrine that instructs the State to undertake certain responsibilities pertaining to the social sphere.

India’s Constitution was an outcome of a multifaceted political movement. The freedom struggle was not only about getting rid of British rule; instead, it aimed to achieve an egalitarian social order. Although there was no consensus on the exact meanings of a futuristic, egalitarian society, it was clear to the leaders of that time that social problems, such as communalism, untouchability, gender-based discrimination and economic disparities, could only be handled by an interventionist State. In this sense, the Constitution had two clearly-defined functions. It had to provide a detailed legal outline for making the political system operational. At the same time, a set of directives were to be worked out for the State to function as a moral force. The State, in the constitutional schema, has a moral duty to intervene in the social sphere.

A close reading of the Preamble and the Directive Principles of State Policy suggests that there is a clear proposal of an ideal Indian society in the Constitution. There are four features in it: it is a society which seeks to achieve social justice without giving up the ideals of political freedom and economic equality; it is a society which strives for a culture of dialogue and discussion; it is a society where the dignity of an individual is respected and his/her selfhood nurtured; and, finally, it is a society that celebrates India’s diversity as a strength while asserting its intrinsic unity.

This imagination of a constitutional society is certainly premised on a belief that electoral politics and, for that matter, democracy are merely instruments to think the unthinkable and to achieve something that seems to be unachievable. The spirit of the Constitution, hence, encourages us to demand and expect a positive politics of hope and aspirations.

Hilal Ahmed is Professor, CSDS, New Delhi