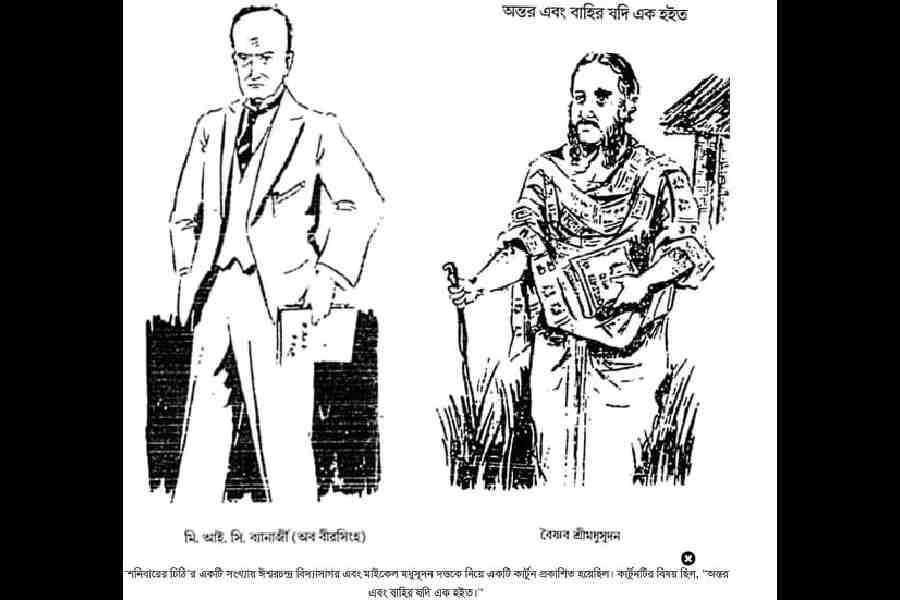

Sajanikanta Das was a lively presence on the Bengali literary scene in the last century, his scholarship matched by his wit. His journal Shanibarer Chithi published a cartoon with figures captioned “Mr I.C. Banerjee” and “Vaishnav Shri Madhusudan”. The latter, though draped in a namabali, is clearly Michael Madhusudan Dutt, the first great poet of the Bengal Renaissance, a Christian convert and Westernized dandy who reportedly had his shirts laundered in Paris. I.C. Banerjee “of Birsingha”, in a suit and tie, is Ishwar Chandra Bandyopadhyay: ‘Vidyasagar’, as the world knows him, was a degree or academic title. A master Sanskritist, he sported a dhoti, chaddar and chappals all his life, defying the dress code of his government job.

Tagore argues that Vidyasagar’s aggressively Bengali garb signified a self-respect and independence of mind that Tagore associates with the European rather than the colonial Indian ethos. He finds the same free dignity of spirit in the unlearned Santhals with whom Vidyasagar consorted in his last years.

Tagore’s comment is finely balanced. He deplores the slave mentality of the average colonial bhadralok. But he hails a rarer Indian spirit that can prevail over the Western. There is nothing imitative about Vidyasagar’s proud temperament. It testifies to a deeper humane essence of his being.

This humanity is not merely emotional or psychological. It engages the rational intellect and the pursuit of knowledge. As principal of Calcutta’s Sanskrit College, Vidyasagar drafted certain “Notes” on reforming its academic programme. The primary goal, he declared, must be “the creation of an enlightened Bengali literature”, meaning not only imaginative works but all texts or ‘letters’. This required the “collect[ion of] materials from European sources” whose incorporation in Bengali called for the linguistic skills of Sanskrit scholars. Hence “the necessity of making Sanscrit scholars well versed in the English language and literature”. Vidyasagar worked this synthesis in his college’s curriculum, to the disapproval of James Ballantyne, the British principal of the Benares Sanskrit College.

Here, then, a century before its formal launch, is the groundplan for a ‘three-language formula’, much more integral than the actual post-Independence model. That was a cobbling together of disparate elements of our diverse geography and history. Vidyasagar’s, by contrast, was an organic construct. Each element meshed with the others in a unified agenda covering three worlds of knowledge: the venerable pan-Indian tradition, its particular regional development, and the international scene. This knowledge was to extend to “the mass of the people” through a network of “Vernacular schools” teaching “Vernacular class-books” through teachers who were “perfect masters of their own language” but possessed of “useful information” from modern Western learning. The composite curriculum of Sanskrit College was designed to train such teachers. In his time as Assistant School Inspector, Vidyasagar toiled to set up such schools, including some for girls that did not take off.

In a rejoinder to Ballantyne, Vidyasagar stressed the importance of the “advancing science of Europe”, which may often depart from traditional Indian wisdom. In this, he follows Rammohan Ray in the latter’s 1823 letter to the Governor-General Lord Amherst. The East India Company provided funds only for traditional oriental learning, first at the Calcutta Madrasa and then the Sanskrit College. The latter proposal prompted Rammohan’s futile letter of protest, calling for instruction in “Mathematics, Natural Philosophy, Chemistry, Anatomy and other useful Sciences” as cultivated by “the Nations of Europe”. This agenda was already in operation at the Hindu College, founded by Indians with some European support. Many of the Hindu founders were doctrinally conservative, hence the reformist Rammohan wisely remained in the background; but they were all committed to the Western model of a secular “liberal education”. Hence the Hindu College did not impart Sanskritic learning. It was left to Vidyasagar in mid-century to synthesize the Indian and Western knowledge systems in its neighbouring institution.

This account bears on the polemics sparked by a recent lecture by Prime Minister Narendra Modi. He charged the Anglicist agenda of Macaulay’s 1835 Minute on Education with inculcating a slave mentality among Indians to this day, denigrating and destroying the indigenous knowledge system and ethos.

The prime minister may be right about Macaulay’s Minute and its stultifying effect on Indian education. But he underestimates the power and resilience of traditional Indian learning and the creative intellection of the evolved Indian mind. Rammohan predates Macaulay. Vidyasagar comes later but strikes out his own path. Already by that date, the Indian genius is making its own syntheses of East and West, combining their multiple legacies in radical innovations leading to the Indian Renaissance and an important strand of the freedom struggle.

We must not misrepresent our inheritance from colonial times — not what the British left behind but what, if we but looked, our own countrymen created and bequeathed us. We neglect it owing to an epistemic change. Rammohan and Vidyasagar laid the foundations of a legacy that is fundamentally inclusive. In Tagore’s words, it

gives and takes, blends and is blended. We, by contrast, divide and contend, grubbing among the fragments for petty gains. We seize upon one component and either embrace or reject it in isolation, oblivious of the damage to the total edifice.

Hence for us, learning English necessarily implies neglecting the mother tongue: never mind that our bilingualism is not only a cultural resource but a huge economic asset. China and Japan did not deliberately shut out English: that was a historical lack they are now making good. Again, for us, following a single branded religion or a particular rigid version of it means excluding and persecuting all others. We thereby disown the precious syncretic traditions holding our society together. Worse, we sow the dragon’s teeth of violence and discord where we could have reaped the harvest of peace.

We thus confine ourselves to the detritus of our colonial past. We see our uniquely mingled inheritance as either/or alternatives, relinquishing all rewards but one. We thereby ensure losing even that, while the ghosts of Macaulay, Clive and Curzon sit among the ruins

and laugh.

Sukanta Chaudhuri is Professor Emeritus, Jadavpur University