Bengali cuisine often announces itself through sweetness, but food historian and author Chitrita Banerji began the session by drawing attention to salt. The small mound of nonta (salty) condiments traditionally placed on the plate, she explained, represents choice, restraint and culinary confidence.

“Cooking and spicing was considered an art, and the moderation of the cook made it an art,” Banerji said, noting that salt, ginger and green chillies allowed diners to adjust flavour to personal preference.

She also located salt within histories of scarcity. “Noon bhaat aar lobon comes up repeatedly in Bengali literature,” she said, reminding the audience that rice and salt were once the most basic form of nourishment for many.

Mishti as food, ritual and refuge

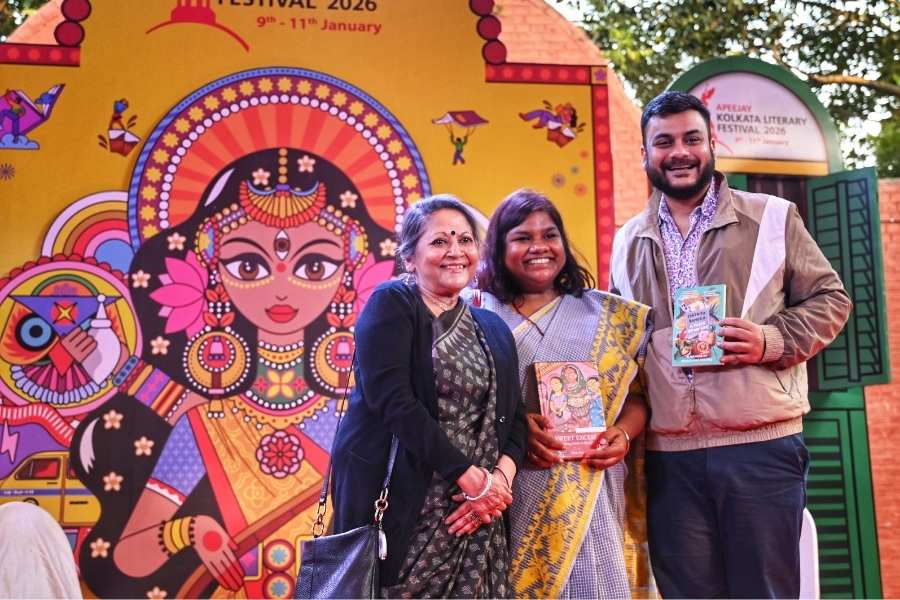

Sociologist and author Ishita Dey

Sociologist and author Ishita Dey shifted the focus to mishti, not merely as a dessert but as a social system. “Mishti dokans were probably one of the first places to eat out,” she said, describing how sweet shops doubled as resting points for travellers, complete with benches and water.

Dey stressed that mishti could function as a full meal.

“Doi could be a meal in itself,” she said, recalling how even the leftover doi jol is shared within neighbourhoods and eaten with rice or muri.

Nolen gur and the loss of intimacy

Chef Auroni Mookerjee steered the discussion towards Bengali ingredients under threat

Moderator and chef Auroni Mookerjee steered the discussion towards ingredients under threat, especially nolen gur. “How do we sustain these practices without turning them into another homogenised commodity?” he asked.

Banerji responded with a memory from Bangladesh, where tasting fresh khejur rosh at dawn left a lasting imprint. “What comes back to me now is not just the taste, but all the sensory associations,” she said, expressing doubt that such experiences can survive industrial speed and profit-driven production.

The missing ‘karigor’

‘Tok Jhal Mishti’ revealed Bengal’s cuisine as a delicate balance of taste, labour and memory

Responding to a question from My Kolkata on the shortage of skilled sweet-makers or ‘karigors’, Dey highlighted structural challenges.

“It’s backbreaking work with long, irregular hours,” she said, adding that informal hiring, regulatory pressures and lack of recognition have pushed many karigors into other professions.

She argued that naming and honouring craftsmen, alongside reforming work hours, could help restore dignity and continuity within the trade.

‘Tok Jhal Mishti’ revealed Bengal’s cuisine as a delicate balance of taste, labour and memory, shaped as much by what is preserved as by what is disappearing.