Recounting the life of her mother, freedom fighter and former INA officer Captain Lakshmi Sahgal, CPM leader Subhashini Ali on Saturday said her political evolution “never stopped at any one stage” and was shaped by both nationalism and a deep desire for personal and collective freedom.

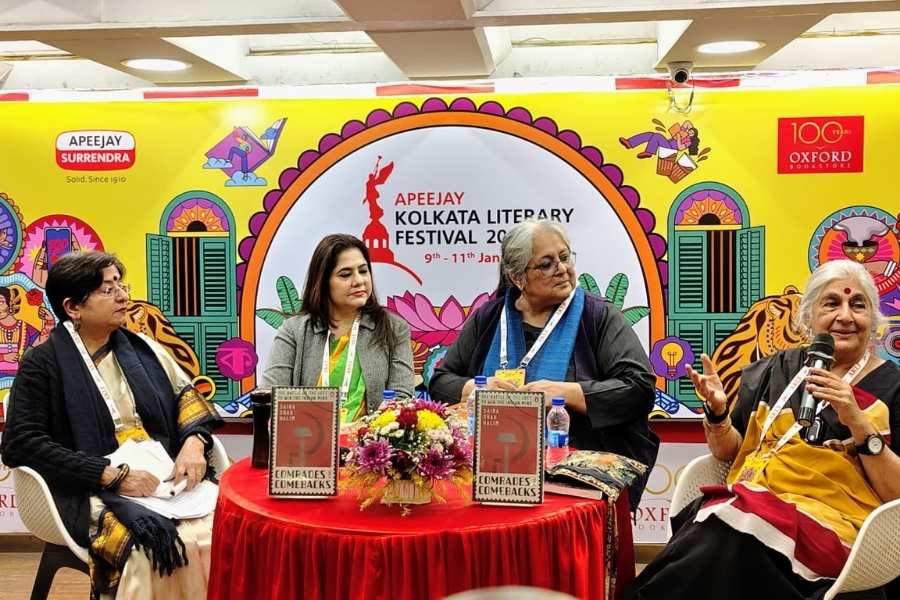

Speaking at the Apeejay Kolkata Literary Festival 2026 during a panel discussion titled ‘Ghare Bairey: Women, the Nation and Life’, Ali said Sahgal’s political consciousness began early. “As a student, even as a small child, when the Swadeshi movement started, she was burning foreign clothes and dolls of the whole area and her own home,” Ali said.

Though Sahgal was “more interested in literature,” Ali said she chose to study medicine because she felt “India would become independent and would need doctors.”

During the Second World War, Sahgal left India to avoid being recruited by the British. “That was the patriotic reason,” Ali said, adding that personal factors also played a role.

In Singapore, Sahgal was practising medicine successfully when the British Indian Army surrendered to the Japanese and the Indian National Army was formed.

Ali said Sahgal was allowed to continue working in a government hospital, while her future husband, Prem Kumar Sahgal, joined the INA.

“That’s when she embarked on her career of theft,” Ali said, explaining that her mother “would steal medicines and supplies from the hospital” every day to treat wounded INA soldiers.

Ali recalled Sahgal’s immediate response when Subhas Chandra Bose asked her to lead the Jhansi Ki Rani Regiment. “He said, ‘When?’ and she said, ‘Tomorrow. I’ll lock up my clinic and I’ll be here and I’ll start work,’” Ali said.

She emphasised that the women who joined the regiment were not from privileged or so-called martial backgrounds.

“They were Malayalees and Tamil women, children of plantation workers, petty shopkeepers, small clerks — very, very poor people,” Ali said. “Very undernourished girls. But they came flocking wherever Netaji and my mother would go to recruit.”

Ali said most of these women had never seen India. “They were the granddaughters and great-granddaughters of indentured labourers,” she said. “They had never stepped on Indian soil, but they were ready to die for this idea of India’s freedom.”

Quoting Bose, Ali said, “Women will fight much harder than men because they’re not only fighting for the freedom of the country, they’re fighting for their own freedom.”

For many women, she added, joining the INA was also an escape from conservative family structures and early marriage. “This was a chance to experience something different, to go in for a very different life,” she said.

Ali said the contributions of these women remained underrepresented in history. “Things are being written, but I think more should be written and more should be known about those women who came from the diaspora into the INA,” she said.

She also linked the historical struggle to contemporary issues, arguing that women’s emancipation cannot be separated from caste, class and communal violence. “It cannot be seen in isolation,” she said, warning that erosion of constitutional values posed a serious threat to women’s rights today.

The other participants at the panel discussion were academician Aparajita Dasgupta-Sengupta, and politician Saira Shah Halim, moderated by Kavita Punjabi.