Senior CPM leader and former MP Brinda Karat on Saturday said India is witnessing an “undeclared Emergency” after 2014, drawing explicit comparisons with the 1975-77 Emergency and warning of a sustained assault on workers’ rights, civil liberties and the justice system.

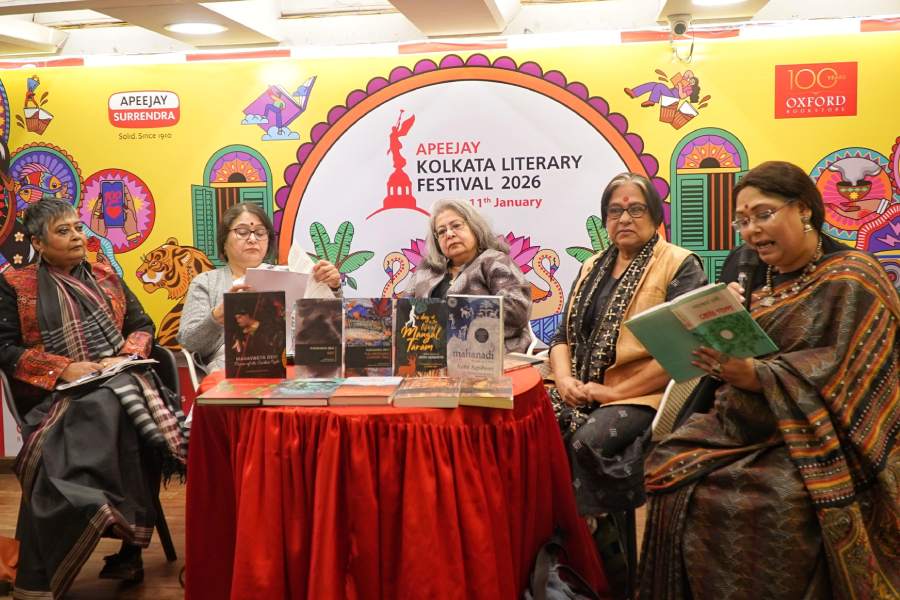

In a conversation with Subhashini Ali at the Apeejay Kolkata Literary Festival 2026, Karat said the political climate described in her memoir, An Education for Rita, was returning in a more entrenched form.

“Trade unions were banned, most workers’ rights were taken away,” she said of the Emergency. “And the way you had to work at that time — that time is coming again, I can tell you.”

Calling the present phase an “undeclared Emergency”, Karat said, “This is not two years of Emergency. This is an undeclared area where workers’ rights are being stripped of their rights.”

She contrasted the post-Emergency period with the present. “There was a huge explosion of what we considered freedom — the freedom to speak, the freedom to organise, the freedom to actually go out on the road and shout a slogan,” Karat said, adding, “Right now, that’s anti-national.”

Karat said repression today was qualitatively different, particularly for young people. “Young people today have a very tough time because it’s also negative, and it’s also state-organised. You have to fight the state at every level,” she said.

Explaining how her work in the trade union movement shaped her politics and feminism, Karat said, “Being a part directly of the working class movement was really the main thing for me.”

She rejected romanticised views of labour struggles, adding, “It’s really horrible work also. You have to really fight back.”

At the same time, she said capitalism destroyed human potential. “I’ve worked with workers who had no education in the sense of letters,” Karat said. “They didn’t go to school, but they could memorise and quote laws in trade union struggles and in courts.”

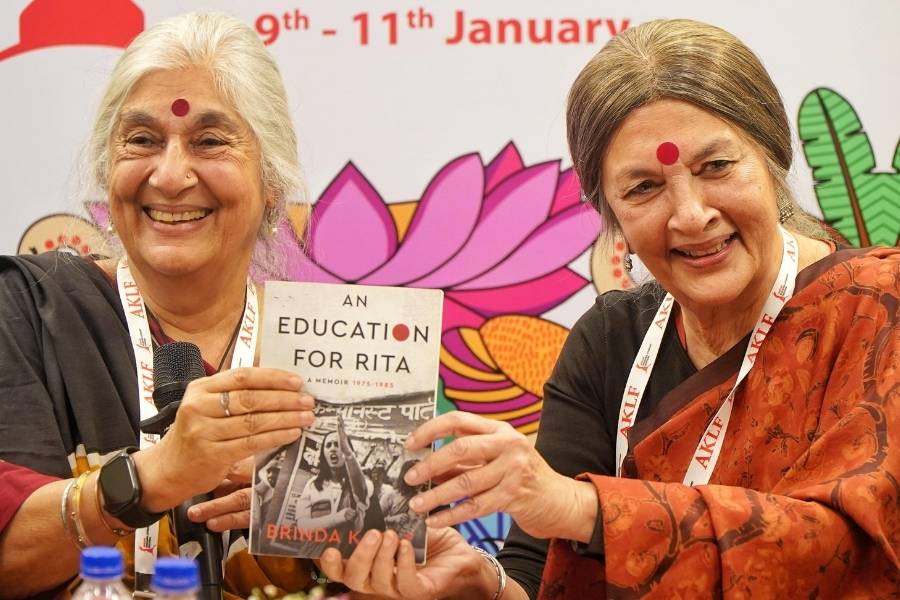

Subhashini Ali and Brinda Karat present the latter's book

Karat drew a parallel between the anti-Sikh violence of 1984 and recent cases of communal violence, including the 2015 lynching of Mohammad Akhlaq.

Recounting her experiences with victims’ families, Karat said the most disturbing change was the loss of faith in justice.

“In 1984, even after everything, she had hope that she would get justice,” Karat said of a Sikh riot survivor. “The day before yesterday, Akhlaq’s wife said, ‘There’s no hope.’”

She described this shift as fundamental. “This is something different. This is the state,” Karat said. “Family after family is being affected.”

Reflecting on the relevance of her book today, Karat said, “It’s the experience of a young woman trying to understand the world. But today’s world is very, very different.” She added, “I think we need a completely different book to understand that.”

During an interaction, My Kolkata asked Karat why was it that the Indian Left, specially the Kolkata unit, responds with alacrity when it comes to international issues — the capture of Venezuelan leader by the US, for example — but the same urgency is seen missing for domestic issues — the attack on Bengali migrant labourers in other states, for instance.

Karat was dismissive about the charge, and said the Left did hit the streets on the migrant labourer issue. “And we must not get into this whataboutery. We are often asked ‘Oh you protest for Akhlaq but not for Dipu Das [a Hindu man lynched in Bangladesh]. It doesn’t work that way”.