These days, Kumkum Naiya is known in Bengal’s South 24-Parganas not so much as the daughter of Dalit activist and writer Dhurjoti Naskar but as a “comic writer”. Their village Dakshin Barasat has a large percentage of people belonging to the Poundra caste, which is listed as a Scheduled Caste. Naskar has long been working for their development. He has been rallying local authorities to build a university, he routinely organises literary and poetry meets, and in general commands great respect from community members. But of late Naiya, 49, has also made a name for herself as the creator of a comic strip titled Didar Golpo.

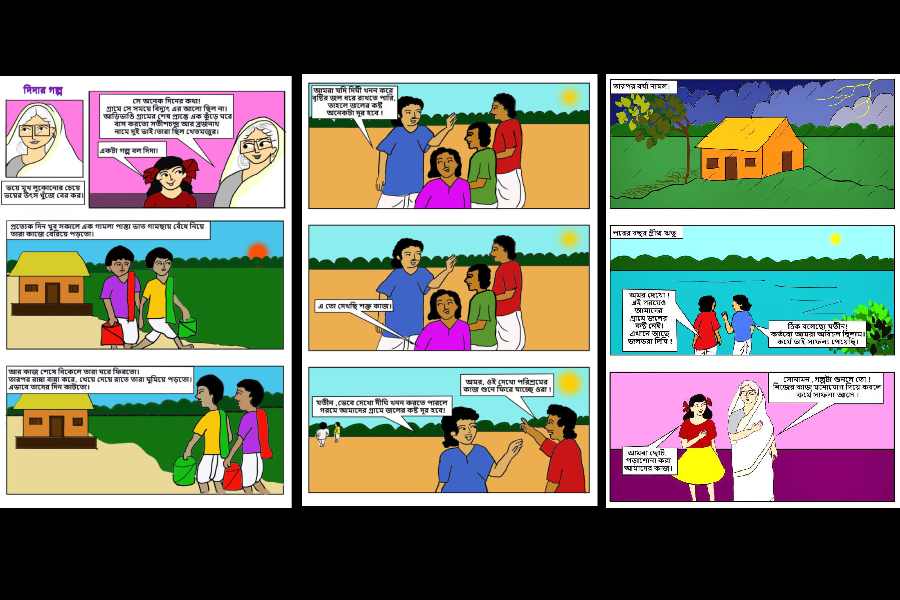

The Bengali comic — featuring a little girl named Sonamon and her dida or grandmother — originally appeared in Sucheta, a magazine focussed on Dalit writings from south Bengal. Now it appears as a comic book, published every two months by Naiya herself.

Sonamon is full of questions about her immediate context — education of the girl child, discrimination based on caste and gender, child marriage, the environment, to name a few — and her grandmother patiently engages with each of them.

But Sonamon was not Naiya’s first choice of protagonist. “I had conceptualised a curious village boy named Bonjhuri,” she says. And then somewhere along the way, she shifted gear. Naiya says, “I wanted to write about the condition of Poundra women. I have seen how our women are marginalised. They are actually doubly marginalised; once because of their caste and again because they are women.” And that is how Bonjhuri came to be replaced by Sonamon and her grandmother.

Didar Golpo

Naiya says, “The older woman is illiterate but has plenty of common sense and wisdom born of years.” Sonamon’s grandmother does not tell her stories of kings and queens but community heroes. Instead of spinning fantasies, she tells her grandchild about the patriarchal ways of society, hurdles from the olden days, the challenges ahead.

Naiya taps into her own life for some of these stories. She tells The Telegraph that in Patkelberia village of South 24-Parganas where her mother grew up, there was no school for girls. “My mother had to cross three villages to attend school. During monsoons, the roads were not usable and in winter, it would be dark before she could get home,” she says. That changed when Naiya was growing up in the 1970s; she went to school in Dakshin Barasat itself.

Naiya’s comic strip is no more than five years old, but she has been writing for the last 20 years. Her books are on the Sundarbans and the lives and struggles of the women there. She also writes about a variety of issues — child marriage, how women must be financially independent before getting married, about the life and teachings of Gautam Buddha — in local magazines. Like many others belonging to the Poundra caste, Naiya and her father are practising Buddhists.

Swasti Sardar Bhowmick, who is also a social activist and a resident of Dakshin Barasat, says, “Initially, Naiya did not publish her work. I read Didar Golpo on her social media page. Then they became popular with the adults, who in turn would read them out to their children.” Sardar, who conducts quiz contests across south Bengal, wants to introduce Didar Golpo in her programmes.

Naiya mostly writes about what she knows, experiences and observations drawn from her travels across south Bengal. “Jamtala, Kaikhali, Jalaberia, Kella, Canning, Piyali, Ghutiari Sharif… I have travelled to every corner of this region for social work,” she says.

In most of these areas, the men go away to other states to work as migrant labourers and the women have to make ends meet. Naiya will tell you how the women go fishing in the dead of the night, well aware that they might fall prey to crocodiles, tigers or snakes. Such is their life.

Naiya has tried to cobble together self-help groups for these women. She says, “They make household items like mats, pots, quilts and brooms. I encourage them to sell these in the city.”

Back to her comic strips. Naiya says, “I chose to write comics and not short stories or any other genre as children seem to prefer them over all others.” Didar Golpo is designed digitally. “I am not a great artist. But I have tried my best,” she says. She is currently working on a series on Gautam Buddha, his life and teachings. Through her work, Naiya critiques the caste system and its practices and lingering prejudices.

She says, “I am planning to write small stories about Poundra personalities. The first one will be about Raicharan Sardar, the first graduate from our community.”

That day is not far when Naskar will be known as Naiya’s father. The elder smiles at the possibility. He says, “I am proud that she is taking forward our Dalit cause. She is voicing her opinion in her way.”