|

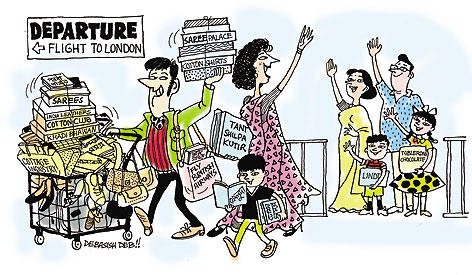

When Lalita visits Calcutta, she is always armed with a long list of things to buy — stuff that she doesn’t get easily in her home-town Delhi. Relatives and neighbours often ask her to get some palm-date jaggery or a particular brand of mustard pickled in oil, or even some of the Chinese sauces that are seldom seen in the markets of Delhi.

But last month, Lalita was a little surprised when she found her elder sister and brother — both settled in the West — solicitously asking her about her impending trip to Calcutta. The reason became clear when she got a long e-mail from them, listing all that they required from the eastern city. One had a list of Bengali books; the other an exhaustive catalogue of cinema.

There was a time, not so long ago, when Lalita’s brother and sister came to India carrying suitcases laden with gifts. No more, though. These days, it is she who sends her siblings an occasional parcel — usually consisting of DVDs of Bengali classics, music CDs and ayurvedic medicines. “There is really nothing much that my brother and sister can get for us, because everything that was once available only in the West is now here in plenty,” she says.

Globalisation has filled the shelves of downtown markets with everything that was once the main attraction of a foreign trip or a West-based relative’s seasonal home-comings. Indian markets today sell the best of foreign foodstuffs, perfumes and clothes. Your friendly neighbourhood grocer stocks everything that you may or may not want — from Italian pasta and olive oil to Danish ham, Swiss cheese and New Zealand kiwis.

“Gone are those days when relatives came carrying everything from pasta to pesto. We have persuaded them not to do that anymore, since everything is available here,” Lalita says.

Tisha Gupta, who has been living in Chicago for the past eight years, agrees. “In the past, my cousins would look forward to the perfumes I got them, but now that everything is here in India, at more or less the same price, it is pointless,” says Tisha. “Save for chocolates, I hardly get anything for them. Not that chocolates aren’t available here but they are cheaper abroad,” she says.

The tables, truly, have turned on the Indian relative. For not only are the malls of new India no different from the huge departmentals of the developed world, India today has things to offer that the non-resident Indian has been hankering after for long years. For the home-sick Indian living abroad, nostalgia now comes in tidy cellophane packages. Old Guru Dutt black-and-whites, romantic Suchitra-Uttam starrers, Bangla bands, Rabindrasangeet and even Hindi remixes — it’s all there in any music shop in the country.

Lalita’s brother, for instance, has an impressive collection of world cinema and is always looking out for a Ritwik Ghatak and a Ray to add to his library. Today, when the DVD market is flooded with films and music — far cheaper in India than in the West — Lalita finds it easy to choose gifts for her picky relatives. “DVDs are freely available and easy to store,” she says, “and light enough to be couriered”.

There are some buying patterns that haven’t changed much, though. For the NRI, it’s much more economical to buy cotton clothes and leather from India. Tisha, for instance, spends at least two weeks shopping for her favourite cotton T-shirts, shoes and bags, and invariably goes back home with excess baggage. From time to time, Tisha’s mother sends her a parcel of all that she is fond of.

The old favourites still make their way from the East to the West, for there is always a demand for exotic things such as batik silk scarves or cloth-bound telephone diaries of hand-made paper. Indrani, a Delhi-based consultant, sends packets of things as varied as tubes of Boroline antiseptic cream and leather shoes to her sister in London. But most relatives usually come back with chocolates — Lindt, Hersheys and, if one gets really lucky, Godiva.

There was a time when India-based relatives of Amitabha Sengupta, a retired cost accountant in Switzerland, looked forward to the grand opening of his bags. “When we were younger, he used to bring us a plethora of gifts — Toblerone chocolates, beautifully crafted building blocks, awesome 80-piece crayon sets, Dior perfumes, Avon cosmetic sets, and synthetic tops and jeans,” says his niece, Piya. And her mother, she recalls, “would be as pleased as punch” with her gifts — cake books and icing sets with five kinds of design moulds.

But everything that her uncle once thoughtfully got for them is there for Piya to buy in any Indian departmental store today. “The magic has worn off,” sighs Piya.

There are still some special things, though, that relatives in India look forward to. Architect Manjari Gupta doesn’t find shoes her size and is happy when her sisters in Germany and the United States carry the right, if somewhat large-sized shoes for her.

For the rest, with normal shoe sizes, the heady excitement of a foreign relative’s suitcases is all but gone. “Recently, my visiting cousin asked me what she could get for me,” says Piya. “I said, ‘Just bring yourself.’”

(Some names have been changed)