|

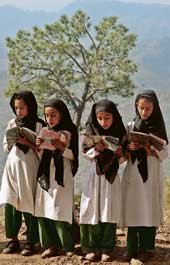

| WORDS WORTH: Underprivileged children ought to be the biggest beneficiaries of the proposed education Bill |

This sounds like a classic example of the gulf between thought and application. And if knowledge is supposed to signify power, this definitely is one case of an empowerment mission tripping on the starting block.

Three years, several drafts and a change of government later, even as it was ready to go in for deliberation in the winter session of Parliament, the Free and Compulsory Education Bill has been pushed to the backburner again. A committee set up by Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and comprising Montek Singh Ahluwalia, deputy chairman, Planning Commission, and C. Rangarajan, chairman, 12th Finance Commission, among others, has been asked to look into its pros and cons, and a report is due in three months’ time.

Education rights activists hope that things will change for the better with the presentation of the report, but fear that if the past three years are anything to go by, there’s no saying how long it might take before education becomes an essential right of each and every citizen of India.

In December 2002, Article 21-A was incorporated in the Constitution of India. “The State shall provide free and compulsory education to all children of the age of six to 14 years in such manner as the State may, by law, determine,” it solemnly stated. However, there was no central legislation prepared to deal with the subject of education, particularly elementary education, in the country.

The Bill was a step in that direction, and its latest draft sought to plug the loopholes in the previous drafts. However, following a volley of criticism from different quarters, things were stayed yet again.

But what exactly are the objections that people have to the Bill? Simple mathematics to begin with. The total cost of the programme ensuring primary education to every single Indian child, if it were to be implemented, works out to an astronomical Rs 53,000 crore a year (it could go up to a maximum of Rs 73,000 crore). Clearly, it’s a sum that should given a serious thought to before the law demands its disbursal.

“The estimates were part of the assessments made by the committee of the Central Advisory Board of Education dealing with the Bill,” says a source at the HRD ministry. “It was also proposed that each state would bear 25 per cent of the expense while the Centre would pay for the rest. However, few states seem willing to do their bit, preferring that the Centre take the entire financial burden upon itself.”

That apart, several other provisions of the Bill seem to have invited criticism. One provision, for example, directs state schools and aided and unaided schools to reserve at least 25 per cent of admissions for the free education of underprivileged children. However, Central schools such as the Kendriya Vidyalayas, Navodaya Vidyalayas and Sainik Schools, have been relieved of the obligation.

“The drafters had originally asked for reservations in Central schools,” says Anita Rampal, professor, Delhi University and an executive committee member of the National Council for Education, Research and Training (NCERT). “But the government didn’t want that.”

Moreover, social activists feel that certain other clauses in the Bill may actually make things more difficult for underprivileged children. For example, though ‘capitation fee’ has been prohibited under Section 15 of the Bill, if a school notifies parents of a certain fee payable during admission, it is technically not a capitation fee. “These provisions give a free hand to private schools to commercialise education and exploit parents,” notes Delhi-based advocate and social activist Ashok Agarwal.

Again, furnishing a proof of residence may be difficult for many underprivileged children, especially those of migrant labourers, say activists. Evidently, these issues need to be addressed before the Bill is implemented. “Public pressure should be kept up in giving the Bill an appropriate form,” says Rampal.

And even when the Bill is finally passed for implementation, there are those who have that niggling apprehension that it may not be done in the best possible way. “As with other things in our country, there is a huge gap between noble thought, which the Bill is a product of, and the will to implement thoughts in the right way,” says Shyama Chona, principal, Delhi Public School.