|

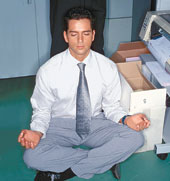

| Stress-busting: The benefits of stress reduction programmes are generally temporary in nature |

Michael Maccari, a men?s clothing executive, was at it 10 to 12 hours a day, fretting over the details of an imminent shipment to stores, the fittings for the spring 2005 lines and the designs for next fall ? three seasons, three sets of deadlines.

But right now, at lunch hour on a Wednesday, the deadlines were dissolving beneath a gentle tide of deep breathing. Dressed in a t-shirt and shorts, Maccari joined 14 colleagues who were arrayed across the floor of a large conference room, holding the downward-facing-dog position, an upside-down V, with their rear ends in the air, arms and legs straight, as if they were playing a game of twister. ?Think of something you can let go of,? said the yoga instructor, Margi Young. ?Something, or some way, you could be doing less.?

The company, Armani Exchange, offers this yoga and meditation class free to help employees relax, reduce stress and recharge during the middle of the week. Similar classes are now familiar in workplaces across US, from old-line firms like AT&T to new economy outfits like Yahoo.

About 20 per cent of employers have some kind of dedicated stress-reduction programme in place, surveys find, and corporate spending has helped fuel what is an $11.7-billion-a-year-and-growing stress management industry, according to estimates by Marketdata Enterprises, a market analyst in Tampa, Florida.

But as the menu of techniques expands to include not only chair and table massages but practices like tai chi, feng shui and energy dances, the trend has prompted some experts to ask how effective the popular programmes are, and whose interests they serve. They wonder if the effects are lasting or just provide a brief break in an ever-longer day. And wouldn?t some employees really prefer a raise to a massage?

Researchers are finding, among other things, that the benefits of stress reduction programmes are generally short-lasting, and may be as useful to a demanding employer as they are to stressed-out workers. All agree that, in part, the courses have sprung up in reaction to the enormous shifts in the nature of work itself.

?The sheer diversity of hours people are working is just startling,? said Dr Harriet Presser, a University of Maryland sociologist whose book Working in a 24/7 Economy explores the social and physical effects of commercial activity that depends on people working at all hours of the day and night. ?For some people, like dual wage earners with kids,? she added, ?the sleep deprivation adds to the stress and it?s like they are never, ever away? from work.

But researchers say companies? interest in stress gurus and breathing lessons has as much to do with pushing workers as it does with real, sustained stress reduction. The programmes took off in the expanding economy of the late Nineties, experts say, when the labour market was tight, and workers? compensation suits claiming damage from stress were on the rise.

?These stress programmes were a part of the concierge services that companies were using at that time so that employees didn?t notice how many hours they were working,? said Dr Peter Cappelli, a professor of management and director of the Center for Human Resources at Wharton School of Business in Philadelphia, ?and they held over since then.?

Time is what most stressed people crave, of course, and this is where mind-body relaxation techniques can backfire. While a lunchtime course may add quiet space to a workday, it can also prime people to put in longer hours. John Sheehey, a business consultant based near San Francisco, had acupuncture for six months while working long hours in Los Angeles. ?Finally, my acupuncturist said, ?Hey, all I?m doing is tuning you up so you can keep running longer.? I think if your tendency is to be a workaholic, it just enables you to do that. If stress is a warning system that you?re about to burn out, all you?re doing is overriding it so you can stay in the game.?

Some providers of stress reduction services acknowledge this effect, said Holden Zalma, the CEO of Metatouch, a massage therapy practice in Culver City, California, whose clients have included Earthlink, eToys and other technology companies. ?We got them all addicted to massage in the Nineties; it was wonderful,? he said. ?But we were very clear that we were not going to fix the stress problem, we were only going to patch it.?

The one workplace stress-reduction technique that seems to outperform all others in preventing the build-up of stress ? rather than reducing symptoms temporarily? is a form of counselling called cognitive therapy. In these classes, people learn to challenge the sort of assumptions about their work that unnecessarily amplify the pressure they are already getting from people around them.

In 18 studies, including more than 850 people working in a wide variety of jobs, this kind of counselling has significantly reduced work complaints, sometimes in as few as six sessions of training.

But there is a catch. The counselling has been tested almost exclusively among the sorts of workers who have some control over their own schedules, like bankers and engineers. When it comes to job stress, control over one?s work may be the most important factor, said Dr Peter L. Schnall of the Center for Occupational and Environmental Health at the University of California at Irvine. Dr Schnall and others have shown that the workers most likely to develop high blood pressure are those who work under deadlines with little control over what the workday will bring, like bus drivers on heavily travelled routes or nurses in frantic hospital wards.

In this economy, stress managers need stress management too.

?NYTNS