A crisp winter afternoon at the Royal Calcutta Turf Club (RCTC). It is the first day of the year and also Derby day. The place is brimming with men and women — children are not allowed. Tweed jackets, sharp suits, floral dresses, pleats and ruffles, aviators and wayfarers, and hats, lots of hats. The betting corners are easy to identify by the squiggly queues. Those betting can be identified by the small booklet in their hands; it contains names of the horses, their track record, details of jockeys and owners. The air is an infusion of beer, wet earth and grass. The crowd is a mix too. Suddenly, the commentary on the loudspeaker rises above the chatter; the larger-than-life screen shows horses and men on saddle ready for the race. And it begins. Screaming. Cheering. Cursing. Horses break into a canter with jockeys fused atop, all in the same position, all bent over like track cyclists. Faster and faster and faster. As the pulse quickens, the audience chant climbs in tandem — “Sun Power, Angels Kiss, Constantinople...”

In the world of horse-racing, horses understandably get all the attention but much of the thrill and the outcome hinges on jockeys. It seems for every race a jockey has to ride a different horse, depending on the owner. “The owners and the trainers decide which jockey will ride which horse. Every time we saddle up, there is a risk. We do not know what is going to happen,” says Nikhil Naidu, who at 21 has a reputation of being one of the most promising young jockeys in Calcutta.

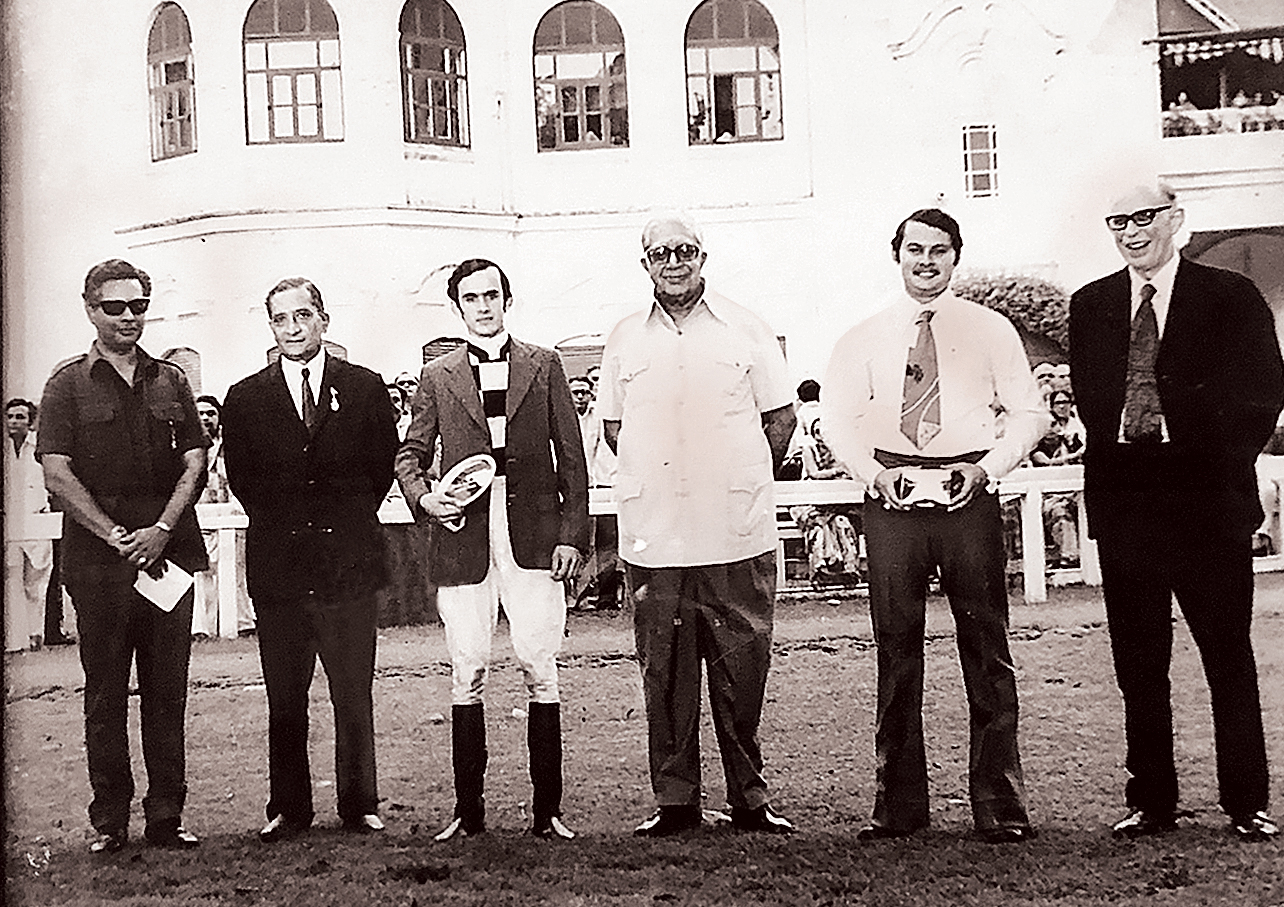

TRACKMEN: Robin Corner (third from left) post a race sometime in the 1970s (Pic: Robin Corner)

Last year, Nikhil had fallen off a horse thrice. Apart from minor injuries, he sustained a punctured lung, a cut on his chin, an elbow injury. He points to a butterfly-shaped mark on his upper arm where he was bitten by a horse.

While people call Nikhil the Varun Dhawan of horse-racing, his mentor Christopher Alford, who has been Calcutta’s champion jockey for seven consecutive years and currently holds all the records in the city, is regarded as the Amitabh Bachchan.

The 43-year-old has in his 25-year-long career broken his ankles, dislocated his shoulders, injured his wrists and collarbones. He says, “Once my horse made an awkward jump and I hurt my back — L4 and L5. The best of doctors said I would not be able to return to racing. But I consulted a doctor in Pune, got some therapy and after three months I was back on the tracks.”

Adds Christopher with much ado, “Jockeys are gutsy. I have never seen one who has fallen and said he will not race again.”

The life-stages of most jockeys are somewhat like this — apprentice, jockey, trainer and, in rare cases, horse-owner. Richard Alford is a trainer — one who trains horses for races. Trainers work like mediators between horse owners and jockeys, and before every race, it is the trainer who briefs the jockey about the horse and tells him how to ride it.

Christopher Alford, who has been Calcutta’s champion jockey for seven consecutive years (Picture sourced by The Telegraph)

Richard owns a couple of horses now, but he was a jockey for 20 years of his life.

His grandfather was a jockey. His father, R.D. Alford, was a jockey. His uncle, Tom, was a trainer. His son, Rutherford, has been a jockey and is now a trainer. “I have been born and brought up with horses,” he says with a smile and continues, “Jockeys are the pilots. Without them how will the aircraft fly?”

Passions will often gallop down the bloodline, and jockeying is no exception. There is a lot of talk about born jockeys, those who have an inexplicable innate connection with horses. There was a time when most of the jockeys were of Anglo-Indian descent — Noel Remedious, Butfoy, Devaney, Robin Corner, Nelson Reuben; a fact Richard brushes off as mere coincidence.

As it turns out, a jockey becomes a jockey after rigorous training and from maintaining a strict fitness regimen. Robin Corner, who is currently the vice-president – racing of RCTC, started out as a jockey. There is a black-and-white photograph in his office where he is seen standing in his riding gear with five officials after a win. “From the body language of the trainer, the jockey and the owner, I can tell you what exactly they are talking about,” he says rather mysteriously, if only to emphasise the kind of expertise one wields when one starts from scratch.

Jockeys usually start out when they are still in their teens. Nikhil went to the RCTC Apprentice Jockey School in Calcutta after completing Class X. He was 15 then. He says, “The four years in jockey school, away from my family in Kammanahalli in Karnataka, trained me to be a complete professional.” He continues, “A jockey needs to know horses inside out. I remember, we would practise in the mornings with the trainers’ horses, come back and wash, clean and feed the horses of the RCTC school, then hit the gym and exercise. In the evenings there was more riding.”

The next and possibly more difficult bit — a jockey has to keep his weight down, mostly between 50 and 52 kilograms. He has to check his weight every day; even a 100 grams extra can be a big, and debilitating, deal.

Christopher has not celebrated a Christmas dinner or a New Year’s Eve party with his family for 25 years now. He does not have a bite of his own birthday cake. When Nikhil goes home to Kammanahalli, he locks himself in his bedroom during meal times — to avoid seeing or smelling food.

Says Nikhil, who is lean with wiry arms, good biceps and broad shoulders, “We drink just one or two sips of water a day when we are dieting.” Christopher adds, “Some jockeys do not put on weight without the trying, but most of us have weight issues. On a normal dieting day, I skip two meals.”

Apart from dieting, jockeys walk a lot when they have to shed weight. According to Christopher, “If the weight has not come down and it’s nearing race day, we get into the sauna box, at 70, 80 or 90 degrees, till we knock off those extra grams.” An ideal jockey has to be as light and strong as possible.

Once on track, a good jockey knows what horse he is riding and its habits. He also knows which horses and jockeys one is up against and their traits too.

Says Nikhil, “During races we hear people abuse from the stands, but riding a horse is not a cakewalk. It is a living thing, it has its own personality.” He pulls up a video on his phone. It shows a horse running into a railing. “After the race, we realised the horse was blind in one eye. She got a cut on her shoulder and had to retire,” he explains. There have been instances when Nikhil took a tumble during a race, had another horse trammel over him and received one or more stitches in the bargain.

Nikhil Naidu is among the current crop of successful jockeys (Picture sourced by The Telegraph)

Richard Alford is a jockey turned trainer (Pic: Manasi Shah)

Is it scary to be a jockey, what with the long list of injuries every jockey seems to have? Richard says with a laugh, “You go to the hospital, stay for a couple of months and come back and ride again. It is a part of the game.” Nikhil says, “If you are scared, you cannot be a jockey.”

Being a jockey requires mental strength alongside physical training — the kind that will help you get up and race after falling off a horse, after watching others fall, after watching fellow jockeys die in a race. A week before Nikhil’s first race in 2018, his cousin, who was racing, came around the final bend, his horse fell and he died. “He had 24 fractures and they could not stop his bleeding. He bled from his nose for six hours and died. He was barely 26,” Nikhil recalls. Richard’s son too suffered a fall in a Bangalore race a decade ago and has been paralysed waist-down since. He now trains horses from his wheelchair.

“You need to have sharp reflexes,” says Richard. Nikhil points out how one has to make decisions within a fraction of a second during a race. “When you are in a race, you are not riding for your specific horse, you are actually looking out for every jockey and every horse in that race,” says Nikhil, who uses social media to make people aware of the challenges of his profession as also its thrill.

Jockeys also get to travel all over the country and abroad for races. Richard talks about travelling to Madras and Nagpur in the 1960s. The main winter hubs those days were Bombay, Calcutta, Madras, Delhi and some of the summer hubs were Bangalore, Pune, Mysore, Hyderabad and Ooty.

But at the end of so much of mental and physical risk and jugglery of equine, time and geography, being a jockey is really only a day job with Rs 2,500 at the end of every race — a stipend paid to every jockey for running a race, no matter whether he wins or loses. Of course, the more skilled a jockey, the bigger the price he commands, but even that cannot stop the inevitable deceleration.

A jockey’s career starts to decelerate, and not always naturally. Sometimes it is age, but weight issues and irreparable injuries sustained during races also contribute.

Christopher laughs it off saying, “When you are on the horse you do not feel anything, the pain only comes before and after.”