Riga (Latvia), Sept. 8: When several prominent Americans, outraged by what they saw as a rising tide of state-sponsored homophobia in Russia, called for a boycott of Stolichnaya vodka, they had no more eager ally against Moscow than Kaspars Zalitis.

Zalitis is a gay rights advocate here in Latvia, a Baltic nation with a long and painful experience with Russia’s oppression of minorities.

Then came an awkward surprise: Stolichnaya, Zalitis discovered, is made not in Russia but here in his hometown, the capital of Latvia, which broke free of Russian subjugation more than two decades ago. “I always thought it was Russian,” he said.

Boycotts have long been a blunt and contentious instrument of protest. But efforts to pressure Russia’s abstemious President, Vladimir V. Putin, into dropping a new law outlawing “homosexual propaganda” by getting Americans to dump vodka have provided particularly fertile ground for complaints of good intentions gone awry.

“They thought Stoli was an easy target,” said Stuart Milk, a gay activist and the nephew of Harvey Milk, the murdered California gay rights pioneer.

Vodka is a boycott target over a Russian law, but Stolichnaya is actually made in Latvia.

|

Promoted by influential gay Americans like the writer Dan Savage and the group Queer Nation, the vodka boycott had “good intentions”, Milk said. But he said he knew from previous work in the Baltics for his organisation, the Harvey Milk Foundation, that Stolichnaya had a large Latvian work force. He decided that boycotting the vodka was “misguided” as it would only hurt a company and a country that are at odds with the Kremlin.

Stolichnaya has contributed to the confusion, for decades promoting itself as Russian vodka on the label and going so far as to proclaim itself the “mother of all vodkas from the motherland of vodka” in a 2006 advertising campaign. The Russia link was later dumped, with labels changed in 2010 to read simply “premium vodka”, but by then its Russian identity had been established.

The exact nationality of Stolichnaya, like many global brands, is hard to pin down.

It was made for a time in Russia and simply bottled in Riga but has in recent years been filtered and blended in Latvia. (See graphic)

All of the roughly 100,000 bottles of Stolichnaya produced each day for sale abroad, aside from in Russia, come from a factory here in Riga operated by Latvijas Balzams, a century-old enterprise that ranks as one of the country’s biggest taxpayers and employers. All Stolichnaya sold in the US is made in Riga.

Its principal owner, Yury Shefler, was born and raised in Russia. But accused by Moscow of stealing the Stolichnaya name from the Russian state in the chaotic 1990s, he risks arrest in Russia and has not been there for more than a decade.

The company that controls the brand, the Luxembourg-based SPI Group, is also owned by Shefler. SPI has mounted a vigorous public campaign to show that it is not Russian, does not share the Kremlin’s take on homosexuality and is, as it asserted in a July statement, a “fervent supporter and friend” of those who are lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender.

To that end, the company’s Latvia office has been badgering the bigger of Riga’s gay bars — there are only two — to start stocking Stolichnaya. Anatolijs Skangalis, the manager of the bar, Golden, said he did not sell the vodka simply because he preferred other brands, like Russian Standard. It has nothing to do with the American-led boycott, he says.

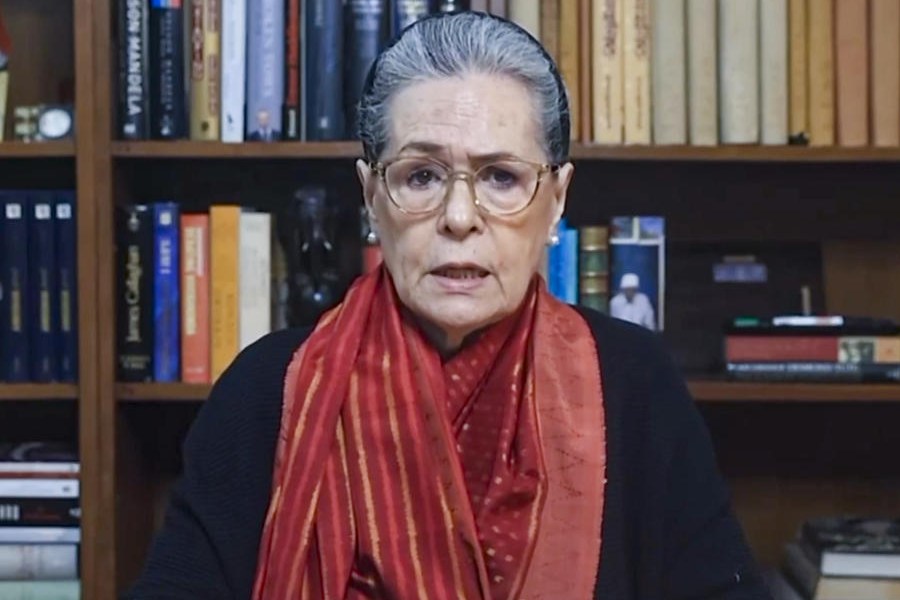

Zalitis, the gay rights advocate in Latvia, opposes a boycott of Stolichnaya vodka, saying the effort could hurt jobs.

SPI Group, he said, is “not trying to hide” its Russian roots — Stolichnaya’s formula, basic ingredients and name, which means capital, all come from Russia — but the company wants to make clear that it is anything but an ally of the Kremlin and that “you will not hurt Russia by dumping Stoli”.

In any event, the Riga Stolichnaya factory says its vodka business, 60 per cent of which is in the US, has not yet been hurt by the boycott, despite reports that a number of bars from New York to San Francisco have started taking the drink off their shelves. It can take several weeks for a collapse of sales to work its way into the production end.

Zalitis, for one, is hoping it all blows over. “If the boycott works, Latvians will lose their jobs. Who are they going to blame? Putin? No, they are going to blame gays,” said Zalitis, who issued an open letter last month protesting the boycott on behalf of Mozaika, Latvia’s only gay rights lobby group.

The European Union requires that Latvia, which joined in 2004, and all other member-states have laws banning all forms of discrimination.

When Latvia held its first gay pride march in 2005, protesters hurled stones at the marchers while politicians denounced the event as a national shame. “The hatred was dreadful,” said Juris Calitis, an Anglican and former Lutheran priest in Riga.

In 2006, Calitis was pelted with animal excrement after he held a church service for people attending Latvia’s second gay pride event. The Latvian Lutheran church then expelled him from its clergy.

But, according to Calitis and gay advocates here, the climate has since mellowed considerably.

Calitis said he did not know whether singling out Stolichnaya would help or hurt gay rights but that he was nonetheless “all in favour of boycotting vodka” regardless of its nationality.

Active for years helping orphaned children and the hungry, he has seen the ravages of alcohol. “If vodka were boycotted here in Latvia, it would be a great day,” he said.