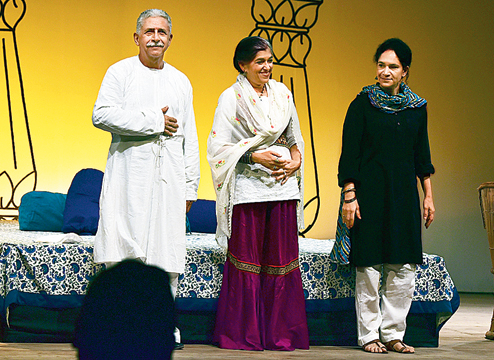

A packed Kala Mandir watched in awe on September 11 as Naseeruddin Shah, his wife Ratna Pathak Shah and daughter Heeba took the stage one by one to narrate three Urdu stories written by Ismat Chughtai in the Motley production Ismat Apa Ke Naam, presented by Kindle Magazine and Weavers Studio in association with t2. Heeba Shah began the evening with Chhui Muee, followed by Ratna’s Mughal Bachcha and Naseeruddin’s Gharwali. Theatre actor-director Koushik Sen pens his thoughts on “the act of ‘not’ becoming”.

“To experience, study, and evaluate the dramatic forms in this subcontinent, to seek the causes of their vitality or decay, to get the feel of our county and our people, the smell of our earth, the dignity, grace and poise of our fellow men, the worlds of their imagination, the motion of their minds, the pulse of their blood — these are the very bases for the study of drama” — this is an excerpt from Ebrahim Alkazi’s The Dramatic Vision, which he wrote in the 1960s for a slide presentation on Indian theatre.

It is now history how Alkazi’s success in Bombay soon caught the attention of the central government in 1962 and he was invited to develop guidelines for a full-fledged curriculum for the new National School of Drama (NSD) that was to be established in the capital. He was also the first director of NSD.

Actor Surekha Sikri took Naseeruddin Shah to see Alkazi Sahib’s production of Othello and Three Penny Opera and he was totally blown away. After the Three Penny Opera show, he went up to Mr Alkazi and said, “Sir, I want to join the school”. It’s very interesting that when Naseeruddin Shah left NSD, he was a dissatisfied man, according to his version — “I had not learnt anything about acting — I had learnt about the history of the craft, etc. But one would go through performances like a drill. One did not know when one had done well, when one had done badly, or why....”

Very recently, when he recounted his memories of the NSD days, he said: “...after all these decades, I have come to the conclusion that any sort of learning kicks in years later. You cannot expect instant results. Things that Alkazi Shahib said to me then keep coming back to me now and make such utter sense”.

On September 11, when Motley presented Ismat Apa Ke Naam in Kala Mandir, the philosophy behind the production immediately reminded me of that portion from Ebrahim Alkazi’s The Dramatic Vision — “to get the feel of our country and our people, the smell of our earth, the dignity, grace and poise of our fellow men.”

Ismat Chughtai’s works, though written more than 50 years ago, still reflect the pulse of the blood of our country, and our people. No doubt, she is recognised as one of the greatest short story writers in the world.

But equally unique was the presentation. The entire format reflects the idea of Naseeruddin Shah’s visions and beliefs about ‘theatre’ and an ‘actor’.

In a conversation with Amal Allana (renowned theatre director, daughter of Ebrahim Alkazi), Naseeruddin Shah quoted Grotowski, who said in his book, “In my training of actors — I do not burden them with skills.”

Naseeruddin Shah himself believes and practises such acting. He mentioned that “the job of the actor is to be messenger. Period. An actor’s job is not to show off his acting, but to serve the text.”

When I saw Heeba Shah, Ratna Pathak Shah and Naseeruddin Shah’s performance on September 11, I completely understood what he meant. None of the three actors were trying to become the characters of their respective stories, yet we could see them.

In Heeba’s segment (Chhui Muee), which is a story of two pregnant women from different social backgrounds travelling on a train — she narrated it so beautifully that we could see the railway station, the compartments, the crowd and sometimes she ‘became’ the characters and then we could smell the pulse of the oppressed, marginalised section of our country, how they live, how they survive, how they fight back and yet celebrate ‘life’. When the poor lady picks up her newborn after giving birth inside the running rail compartment — Heeba smiles while narrating the incident. We could see the baby, we could see the light of happiness in the mother’s eyes, her pain, her pride.

The second story (Mughal Bachcha), narrated by Ratna Pathak Shah, traces the Mughal descendants and their declining status. The relationship between a young man and his wife. The total miscommunication and chaos, frustration and the clash of false egos giving birth to a tragic tale, which made us laugh and cry at the same time.

Heeba mostly restricted herself to a platform and used a book as the only prop while narrating the story. Ratna Pathak Shah used a chair as well. She began her story in a very relaxed way by making ‘paan’ — we all thought till one point of time that she really had all the ingredients inside the dabba — but after a while we could see there was nothing. Every action of hers was so meticulous but without any show-off. While speaking, most of the times, she was ‘doing’ something or the other, but the spirit of the storytelling act was never disturbed. Her voice changed as the young couple grew older — Kaale Mian became old, sick and died a dissatisfied man, without seeing his begum’s face. The dialogue “Ghunghat uthaa” came three to four times in the story. The last time it came as a blow, it was so devastating. We could see the broken man, the unfinished love, the unfulfilled lives of human beings.

Naseeruddin Shah himself narrated the third story Gharwali — about the prostitute-cum-maid Lajo who wants to become the malkin of a household. His performance was like a trap. He made it look so easy, so fluent, so effortless that to every actor it would seem, “Oh, I think I will be able to do this!” But once one starts thinking about it, one realises how tough it is.

He performed like a free-flowing river. We could visualise not only Lajo or Mirza Saab (the two central characters), but the entire village. Doodhwala, the young boy madly attracted to Lajo’s physicality, the greedy Lala, Mirza’s friends — he was switching from one character to the other so smoothly, so quickly — yet he was the ‘messenger’, not the ‘characters’.

Moreover, his performance depicted his love for theatre. Maybe this is why his portion seemed so special and unique.

Amal Allana asked him in an interview, “Does theatre still give you a kick?” Naseeruddin Shah answered: “Oh boy! Like nothing else on earth. The sheer undiluted joy — I cannot explain it. I keep doing theatre because I just love it.”

Is Naseeruddin Shah the finest actor in Indian theatre? Tell t2@abp.in