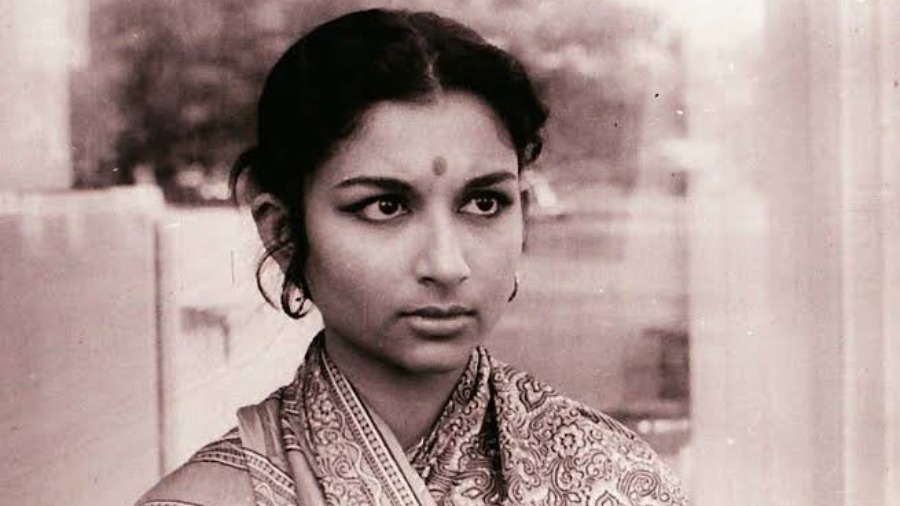

Aparna and Doyamoyee. Champa and Renu. Deepa/Roopa (Suzy) and Madhu/Gauri. Uma and Mansi. Tutul and Aditi. Vandana and Pushpa. Chandi/Kajli and Nimki. Those who know their Hindi and Bengali films will know these as some of the most memorable characters essayed by Sharmila Tagore in a glittering career that scaled both artistic highs and commercial success like few others.

The demure bride, Aparna, in Apur Sansar. The coy Champa in Kashmir Ki Kali. The painfully shy Uma in Anupama. ‘Suzy, the oriental dancer’ scorching the screen to Shankar-Jaikishan’s ‘Le ja le ja mera dil’ (An Evening in Paris) and Vandana doing the same to S.D. Burman’s ‘Roop tera mastana’ (Aradhana). Her filmography shows quite a remarkable variety, in keeping with what she once mentioned, paraphrasing Frank Sinatra, as ‘doing it my way’.

However, in between these characters that are easy to recall, there is a body of work in Bengali cinema that has unfortunately escaped attention. Book-ended by Aparna and Doyamoyee (Devi) in her first two films and Champa and Renu in her maiden Hindi films, both blockbusters, are six Bengali films that deserve to be rediscovered, and how Sharmila Tagore looks back on some of them.

Sesh Anka (1960)

One of the finest thrillers made in India. Haridas Bhattacharya’s screenplay (with Raj Kumar Moitra) can serve as a textbook for the genre. Sudhangshu (Uttam Kumar) is a widower about to marry Soma (Sharmila Tagore). Sudhangshu’s first wife, Kalpana, has died under mysterious circumstances, and Soma has helped him overcome the trauma. Days before the wedding, a woman turns up claiming to be Sudhangshu’s first wife. He alleges that the woman is an imposter. Also in the picture is a shady figure, Samadder (Bikash Roy). A series of twists and turns later, the case goes on trial as the shocking truth unravels.

Sharmila Tagore, in her first appearance after the critical high of the two Satyajit Ray films, is undaunted by the presence of a bevy of stalwarts, including Kamal Mitra and Utpal Dutt as the two lawyers, Pahari Sanyal, Sabitri Chatterjee and of course Uttam Kumar.

Sharmila Tagore:

“With Haridas Bhattacharya’s Sesh Anka, I became a professional actor, that is, I was paid a remuneration. I saw the film recently and I was quite impressed with my performance. Maybe I watched it without being overly critical, knowing that it was my first film outside of Manik-da’s (Satyajit Ray) and as an actor who had not been taught the craft of acting. I was extremely natural and in no way daunted by Uttam Kumar’s presence”

Nirjan Saikate (1960)

Tapan Sinha’s evocative adaptation of Samaresh Basu’s novel of the same name, Nirjan Saikate casts Sharmila Tagore in the role of a young woman jilted in love who is travelling by train to Puri with four widows (played by Chhaya Devi, Ruma Guhathakurta, Renuka Devi and Bharti Devi). On the journey, they meet a young writer (Anil Chatterjee). The often-mystical tale blends beautifully with the desolate sea to provide a fascinating window to the interactions of the dramatis personae and their tragic backgrounds. Like in Sesh Anka, Sharmila is surrounded by a number of big names of the industry and yet manages to make an impact. The National Award for Best Actress for the year went to all five of the women jointly! Aided by superb cinematography, sound design and a pensive yet ironical tone, this is a ‘road’ movie like few others in Indian cinema.

Sharmila Tagore:

“Tapan Sinha had the expertise and vision of a great filmmaker. When I think of Tapan Sinha, I think very fondly of a good human being who led an unobtrusive, down-to-earth life and carried on making meaningful films for a long time. I met Jaya (Bhaduri) for the first time while shooting for Nirjan Saikate. She had turned up with her father who was close to Tapan Sinha. She became very fond of me and we remain friends to this day.

“It was an immensely enjoyable outdoor experience. I am reminded of an enchanting evening. It was pouring. Rabi Ghosh and I decided to walk to the deserted beach to experience the Bay of Bengal in all its frenzy. We took a transistor along and switched it on. There was Ustad Faiyyaz Khan’s majestic voice singing Raga Malhar, a raga associated with torrential rain. Talk about serendipity! Picture the scenario – huge waves crashing down on the sand; the Ustad’s majestic voice challenging, transcending, blending with the roar of the rain-lashed sea. The perfect convergence of man and nature. And Rabi-da and I – maybe insignificant in the larger scheme of this universe – but I would like to believe that the picture would have been incomplete without the two of us there.”

Barnali (1963)

One of the finest romantic films from the golden era of Bengali cinema, thanks primarily to its two winsome lead performances, some exquisite black-and-white cinematography (Bishu Chakraborty) and Kartik Bose’s innovative art direction.

Trideep Sarkar (Kamal Mitra) assigns his nephew Ashesh (Soumitra Chatterjee) the task of distributing his daughter’s wedding cards. Ashesh gets the wrong address and mistakenly invites schoolteacher Biman Chaudhuri (Pahari Sanyal) and his family to the wedding. A livid Trideep, who will not have someone of ‘no consequence’ at the wedding, insists that he go back to tell them that the invitation was a mistake, thus setting the stage for a relationship between him and Biman Chaudhuri’s young daughter Aloka (Sharmila Tagore).

The exchanges between Sharmila and Soumitra give the film its drive and vigour. Note, for example, the effervescence that marks their interaction as they walk on the rain-soaked streets of Kolkata.

Sharmila Tagore is fabulous in a role that requires her to convey how she is making sense of the character’s drives and motivations, and coming to terms with the realisation that she is falling in love with Ashesh (beautifully conveyed in a scene where they go for a boat ride on the Ganga, to the accompaniment of Rabindranath Tagore’s ‘Jokhon bhanglo milan mela’...).

Sharmila Tagore:

“I remember Barnali like it was yesterday… these black-and-white films fascinate me and because Ajoy Kar had been a cinematographer, the camerawork in Barnali was outstanding. There was a rain scene, if you remember, it was a triumph of set design… a taxi arriving, waiting, and Soumitra and I keep bantering away… and you can’t actually tell that it’s not outdoor/indoor… that it’s all part of a set, beautifully done.

“The subject matter is so unique. A wedding invitation delivered by mistake. And then Soumitra is asked to ‘uninvite’ them…. It’s a relationship that grows over an evening and is done beautifully. Soumitra looks so good in his dhuti-panjabi – and conveys the nobility and sensitivity of his character so well. And I am so full of pimples! Yet, the charm of it was the simplicity of the look, not being conscious of my face.

“Beautiful sequences… the taxi ride through the city at night… the scene next to the Ganga ghat and on a whim they go on a boat ride. The whole thing keeps you engrossed. The way the narrative unfolds, the imperceptible changes the characters go through…. The sensibilities are so modern for the times.”

Chhaya Surjo (1963)

Probably the most deglamourised role of Sharmila Tagore’s career. Based on a short story by Ashapurna Devi, this is the poignant tale of a young girl shunned by everyone, including her family, because of her dark complexion and unconventional ways. Ghentu – a flower that grows in the wild and ostensibly serves no purpose – is constantly rebuked for spending time with the boys, playing marbles, cricket and carrom.

Sharmila Tagore is a revelation as the feisty young girl, a free spirit who does not want to adhere to norms dictated by society and yet pines for acceptance for the way she is. That Sharmila Tagore chose to play this role is as much a tribute to her willingness to experiment at an early stage of her career as it is to director Partha Pratim Chowdhury’s vision in casting her.

Sharmila Tagore:

“Working with Partha Pratim Chowdhury was an eye-opener. While Manik-da and Tapan Sinha were more like mentors, Partha was a friend, just a few years older. He understood performances. After working with Manik-da, I found that Partha’s tone was a bit on the overly dramatic side. But it worked…. It was a role that inspired me. I don’t think I had performed like that before. I loved the tomboy aspects of the character, a girl who lives by what her heart tells her. Ghentu really stands out in the roster of characters I have played.”

Kinu Gwalar Goli (1964)

What Kinu Gwalar Goli, which came a year later, lacks in terms of the technical finesse and flow of Barnali, it compensates for with certain psychological aspects in its narrative. Based on a story by Santosh Kumar Ghosh, it offers enough – particularly in terms of the performances, a couple of Salil Chowdhury gems shot on Sharmila Tagore and superlative art direction by Rabi Chattopadhyay – to satisfy a viewer interested in a largely forgotten vehicle starring some of big names of Bengali cinema at the time.

Kinu Gwalar Goli is the kind of dead-end street where dreams don’t just die – they just have no place here…. Sharmila Tagore and Soumitra Chatterjee’s on-screen camaraderie comes through in a series of sequences, not least the one in which they move from the formal ‘apni’ to the more familiar ‘tumi’. Given that neither Apur Sansar nor Devi gave their leads a stab at happiness – Aparna passing away at childbirth, Doyamoyee falling prey to blind superstition – it is tempting to wonder if the worlds of Barnali and Kinu Gwalar Goli are what Apu-Aparna or Doya-Umaprasad would have had if fates had dealt them a better hand.

Shubha Mahurat (2003)

Sharmila Tagore returned to Bengali films after almost two decades with Goutam Ghose’s Abar Aranye (the sequel to Ray’s Aranyer Din Ratri) and Rituparno Ghosh’s Miss Marple-inspired murder mystery. Though the film was feted for Rakhee’s performance (National Award for Best Supporting Actress), in a more author-backed and audience-pleasing role, it is Sharmila Tagore who actually gives Shubha Mahurat its emotional core. She brings a rare gravity to her portrayal of the producer who has more to her than she lets on. It is a wonderfully nuanced act that again begs the question: why haven’t Bengali filmmakers cast her more often after this?

Sharmila Tagore:

“I had been wanting to work with Rituparno. He came to me for Unishey April, but somebody else brought the finance for the film and the casting changed. He narrated Bariwali to me but that too didn’t work out when the film’s finances were finalised. So, I wasn’t sure Shubha Mahurat would work out. It did begin on an unfortunate note, when the media played up the Rakhee versus Sharmila Tagore controversy. I liked my role but I feel I could have done better. There are certain scenes I’m fond of. There’s this scene where I’m painting my nails and talking over the phone. I think it came across as spontaneous. I didn’t quite like my last scene; I felt it could have been a little better. The film ends well though, with the newspapers being delivered and the city waking up to the news. When Mrinal-da [Mrinal Sen] saw the film, he said he had never come across a villain more enchanting!”

Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri is a film and music buff, editor, publisher, film critic and writer