In her book Double Exposure: Fiction into Film, Joy Gould Boyum points out that the POV device can also become absurd or tedious in a straightforward narrative film. Discussing the 1947 film Lady in the Lake, which used this technique to represent the perspective of the leading man (a detective), Boyum says the device worked up to a point, “but when the heroine started moving toward the camera, beginning to embrace and kiss it, the results were ludicrous.”

It is still rare to find a whole film that is shot as POV (one that comes to mind is the 2002 Russian Ark; another is the “found footage” film The Blair Witch Project), but there are countless instances of specific scenes shot in this way. And some of the most effective of these depict a crime or an act of violence. The long opening shot of John Carpenter’s Halloween, for instance, from the perspective of a little boy who kills his elder sister while wearing a Halloween mask; or the opening-credits sequence of Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom, in which a photographer-killer stalks his victims and films them as they die; or the virtual-reality scenes in Kathryn Bigelow’s Strange Days, in which an electronic device allows the user to experience someone else’s memories and physical sensations.

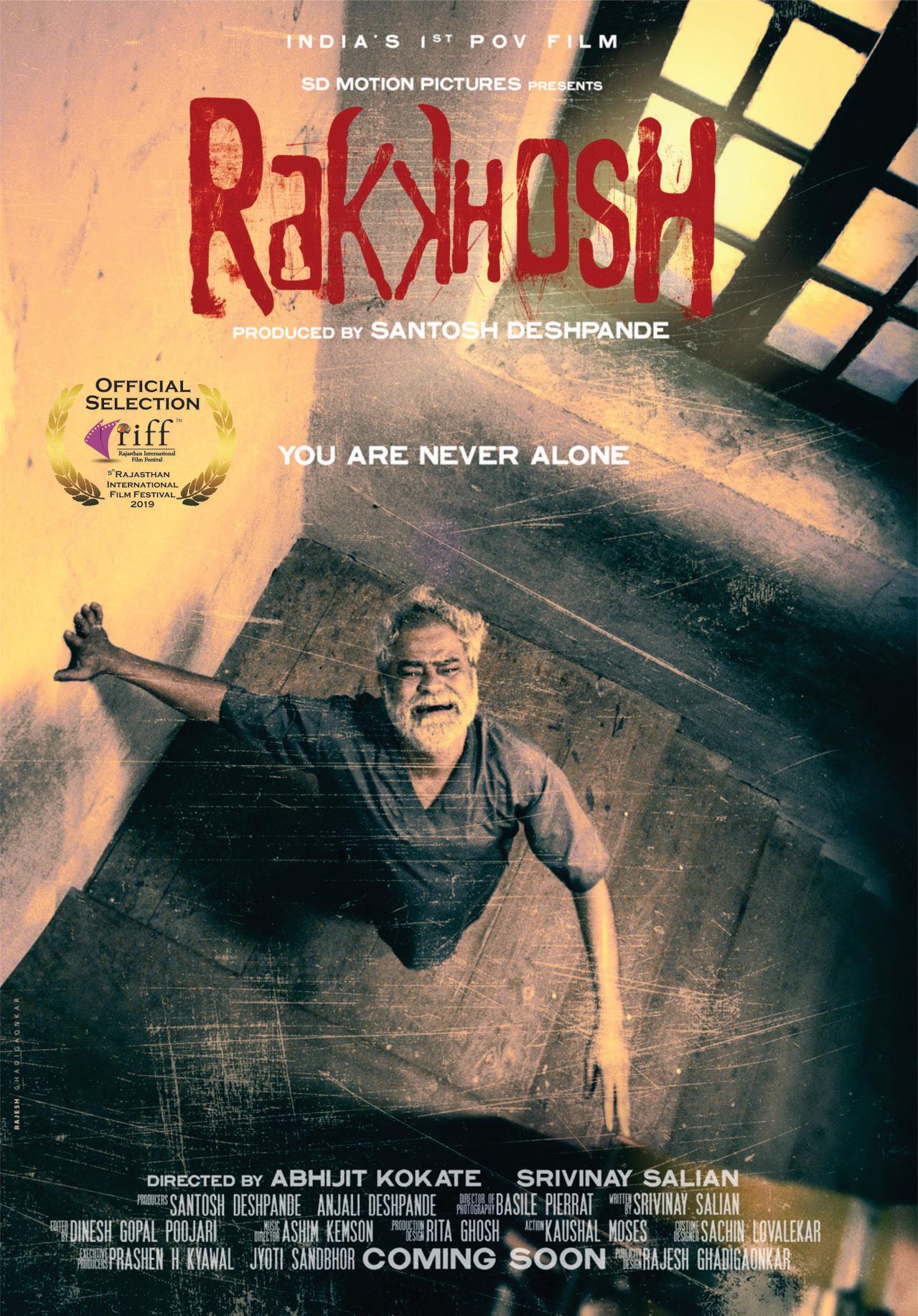

Without giving away spoilers, the climactic sequence of Rakkhosh adopts the point of view of an entity – possibly a supernatural one, or a psychotic – who takes revenge on a number of people, and these are some of the film’s most powerful scenes: it is as if we viewers have been given a Godlike carte blanche to hurl characters around, treat them like elements in an advanced video game. I wonder what it says about our own dark hearts that a POV kiss comes across as corny or fake, but morbid scenes shown from a first-person perspective can be so thrilling.

Eighty years ago this month, a young man named Orson Welles, having just signed a contract with RKO Studios, was putting together a treatment for a film adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s novel Heart of Darkness. It didn’t work out: there were artistic conflicts and budgetary problems (exacerbated by this pesky war that had just begun in Europe, cutting off a large audience for a “serious” film) – and Welles would move on to develop another script, which became Citizen Kane.

What the impact of the never-made Heart of Darkness might have been, we can’t say, but it probably would have shaken many ideas about cinematic form. Because Welles’s major conceit was that the whole film would be told from the point of view of the book’s narrator Marlow – so that the camera’s “eye” (representing Marlow’s gaze) became a direct substitute for the first-person “I” of the novel.

Would that have made for a gimmicky, self-conscious film? Possibly. But knowing this particular enfant terrible, he may well have fashioned something brilliant out of it.

I was thinking about that phantom film as I watched the creepy psychological thriller Rakkhosh – the opening lines of which, coincidentally, point to another heart of darkness. “Sab kehte hain andheraa kaafi daraavna hota hai,” the narrator says, “Par mujhe toh andhere mein hee achha lagta hai.” (“Everyone says darkness is scary. But I only feel comfortable in the dark.”)

Co-directed by Abhijit Kokate and Srivinay Salian, and available on Netflix, Rakkhosh is not an easy watch, and definitely won’t be to all tastes. There are various reasons for this: the claustrophobic setting and subject matter (it unfolds mainly in a dingy mental asylum where a series of murders may or may not be taking place); a certain theatricality in its staging and performances (which may be part of the film’s design); but mostly because, throughout its running time, the camera represents the perspective of a specific character, a paranoid, childlike inmate named Birsa.

Naturally, then, we never see Birsa’s face, only hear his voice as he interacts with his elderly friend Kumar John (played by the always-excellent Sanjay Mishra), a visiting journalist, the asylum’s chief doctor and sinister nurse, and also recalls his past with his family.

This makes Rakkhosh one of the most unusual Hindi films in recent memory, and among the most disorienting. A handheld camera can unsettle viewers even when it is employed to tell a warm, accessible story (I remember how many initial viewers of Mira Nair’s Monsoon Wedding were put off by the occasional “jerkiness” of the footage), but when this technique is married to a dark narrative and we can’t see the film’s protagonist, it can be very challenging indeed.

At the same time, it’s weirdly effective when a suspense-horror film’s POV is that of an unreliable person whose sanity is in question. When Birsa looks at a doll and imagines that it is his “Ma”, we feel we can’t trust the evidence of our eyes. And when the other characters address the camera, stare into it warily, sceptically or fearfully, we feel just as nervous as the protagonist.

Films like Rakkhosh raise interesting questions about what the cinematic equivalent of a novel’s first-person narrative might be. “By subjectivizing the camera to represent Marlow’s point of view, Orson hoped to compel the audience to identify entirely with Marlow,” writes Barbara Leaming in a biography of Orson Welles.

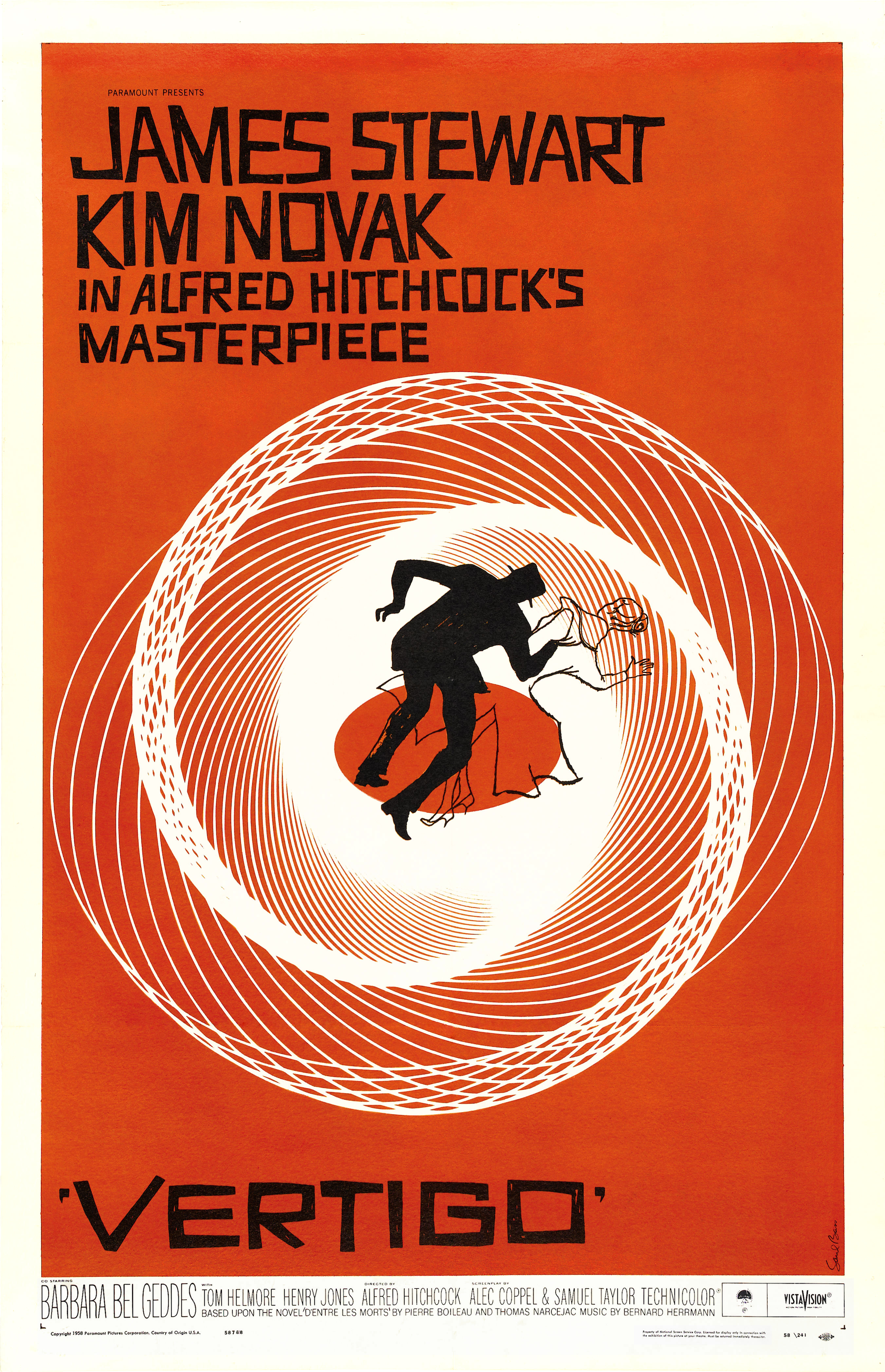

But there is a counterpoint to this idea: as director Francois Truffaut pointed out, if a movie audience is required to identify with a particular character, it is important for them – in a visual medium – to be able to see that character. Thus, a better way to achieve such identification is the more conventional approach of depicting the character on screen, while keeping our perspective limited to what he or she sees. An example I can think of is Hitchcock’s Vertigo, where, for the first two-thirds of the film, we don’t leave the side of the protagonist Scottie (played by James Stewart) –the great revelation in the story occurs at the moment when Scottie leaves a room and the camera, for once, doesn’t follow him out.

In Hitchcock’s Vertigo, for the first two-thirds of the film, we don’t leave the side of the protagonist Scottie (played by James Stewart) –the great revelation in the story occurs at the moment when Scottie leaves a room and the camera, for once, doesn’t follow him out (Poster of the film)

Jai Arjun Singh is a Delhi-based freelance writer and critic who writes mainly about books and films