A little after seven. Saturday evening. Kala Mandir full and brimming and abuzz. A darkened stage and what looks like an old fashioned kind of set design. Nothing wrong with that. Meanwhile, lots of theatre going on in the aisles: a dozen conversations, inane greetings, the ubiquitous cellphones abuzz or clicking.

The first bell. The opening announcements from a dignified rostrum seem a little self-adulatory. And then it’s finally time.

The hall darkens and that wonderful feeling in the pit of the stomach. The lights dim to the opening bars of an oddly chosen classical guitar piece.

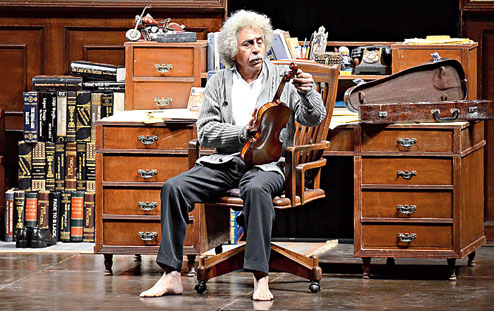

The music seems a tad too long but it’s clearly building us up for the grand entry. Stage light on. You do a double take. Einstein shuffles on stage. The scraggly white afro. The unmistakeable face. The nonchalance of easy genius that doesn’t take itself too seriously because it has looked into the infinite vastness of time and space and has understood how infinitesimally great and infinitesimally small mankind is in the rolling rhythms of the universe.

Genius sits itself in a revolving chair, back to audience, deliberately, setting up suspense as you wait for him to turn and face you. A good four, five minutes of monologue before he does. A discreet piece of direction that shows an intuitive feel for theatre.

It doesn’t matter that Gabriel Emanuel’s play isn’t fantastically well written, or that it is a single monologue freewheeling through the time and space of Einstein’s mind and witty one-liners. It often leaves you, as the performance progresses, wondering where you are — in the great man’s room; in the great man’s mind; in a proscenium theatre where with deliberate savage intent the fourth wall is deconstructed; in Kala Mandir where the side doors repeatedly open, and close upon some self-consciously hasty exits: and for a moment you’re distracted and you wonder what Naseeruddin the artiste feels about that kind of behaviour and disrespect.

But it doesn’t matter because with elegantly professional indifference to the uncalled for exits, and the constraints of an unremarkable play, and the quirky obdurate challenges of a one-character drama, Naseeruddin Shah, for 75-odd minutes with a barely 60-second blackout in the middle to denote a change of Act, commanded the stage in virtuoso performance. Naseeruddin’s Einstein was indeed a masterclass in acting and histrionics.

Only the very best kind of actor makes you forget that you’re watching a play and insidiously bamboozles you into believing that the illusion is real. That’s the kind of magic Naseeruddin conjured up, and not once did this great actor play to the gallery.

The guttural tones were articulate of the character. The voice of an old man, not faltering but strong. There was quietness and wit and passion and sorrow and mischief and matter-of-factness. The torrent of words came at you compelling, convincing, rising, falling, swelling, slowing, and then searching for silences in-between, so that you felt the richness of the life and the accumulated experience and knowledge and understanding that had shaped it. And you knew that he had been touched by life. That’s how real, frightening real, Naseeruddin made the character.

Of course the show had its little idiosyncrasies. And one wished that the violin, which Naseeruddin took up more than once, would actually get played once he had found the bow lurking unseen on the armchair on stage.

And yet it all came together seamlessly, simply because of the effortless ease with which Naseeruddin slipped into the part. So consummate was the performance that it was as though he was not acting at all. Chatting, remembering, picking up papers, talking physics, recalling lost romance and marriage, slipping in wicked one-liners, eyes glinting, lighting a pipe, donning a coat, contemplating nuclear meltdown, pulling off socks, rubbing weary feet and toes, Naseeruddin’s Einstein was a master play of stage business that made up for the lack of plot and action and character. This kind of play is better suited for a small intimate hall. Yet Naseeruddin had a thousand-odd people, barring the odd self-conscious hasty exit, in thrall, acknowledged at the end by a thunderous ovation.

Thank you Mr Shah. Please take another bow.

(The author is the vice-principal of St. Xavier’s College and a professor of English)

Thus spake Einstein. We couldn’t agree more!

• God is subtle, but he is not malicious. Not yet.

• I never travel first class. It doesn’t arrive any sooner.

• I am supposed to sleep at night. But then I would miss the stars!

• Speed of sound? Am I supposed to know it... I do not have a memory for details... I hate to memorise.

• It is never a mistake to question, never.... The important thing is not to stop questioning.

• Sit on a hot stove for a minute and it feels like an hour! Talk to a pretty girl for an hour and it feels like a minute.... That is relativity for you in a sentence.

• Devil and God. What is the difference?

• Politics is more difficult to understand than physics.

• Either you are for war, or you are against it.

• The world war after the next one will be fought with rocks.

Text: Sibendu Das