|

| Paul Bhattacharjee who plays Benedick and Meera Syal as Beatrice in Much Ado About Nothing |

Anjana Saha is in for a dramatic treat when she returns to England in September — she will be able to see the Royal Shakespeare Company’s lavish new production of Much Ado About Nothing.

This is set not in the port of Messina on the Italian island of Sicily, as in the original first performed in 1598-99, but is transposed to a contemporary farmhouse outside Delhi where the characters use mobile telephones.

Anjana is a vivacious young woman who is the vice-principal of Delhi Public School in New Town, Calcutta. “I also teach poetry and elective English and run the theatre club in school, so I wear many hats,” she says.

Last year the RSC and the British Council brought Anjana to the theatre company’s headquarters in Stratford-upon-Avon to attend an international workshop aimed at showing how Shakespeare can be made more accessible for Indian children by giving the Bard, say, a Bengali flavour.

This is not exactly new, Anjana points out: “Back home in Calcutta at Minerva theatre, Soumitra Chatterjee has performed Raja Lear.”

Still, coming to Stratford has given Anjana the chance to tour the RSC’s new theatres, see the swans gliding gracefully on the River Avon, and, of course, visit the idyllic countryside and especially the Holy Trinity Church where Shakespeare was buried on April 25, 1616, with the exhortation: “Good friend, for Jesus’ sake, forbear/To dig the dust enclosed here;/Blest be the man that spares these stones/And curst he that moves my bones.” Will he now turn in his grave to see his plays transposed to modern India or would he have much rather worked in Bollywood?

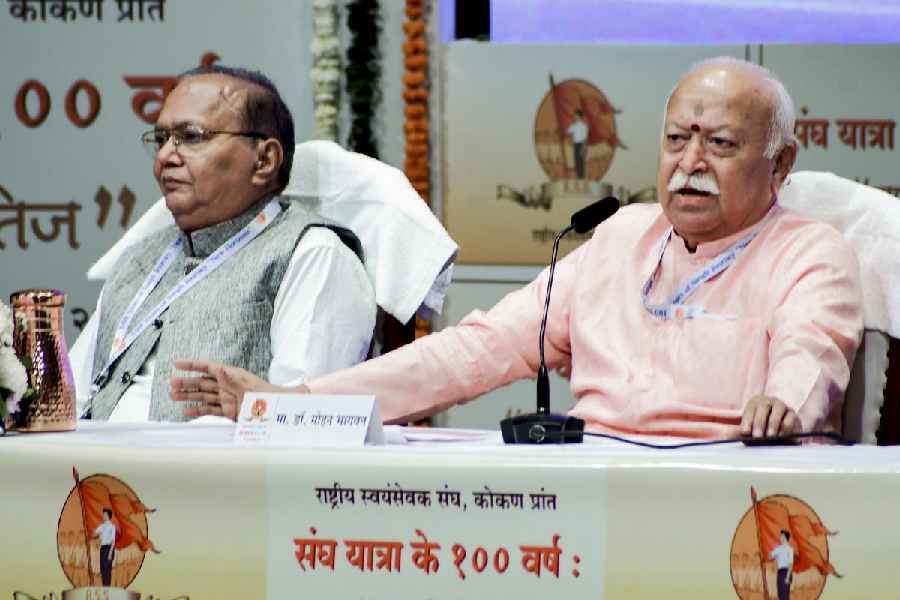

Two minutes’ walk from the church is the Courtyard Theatre where Much Ado About Nothing is currently being staged, with an entirely British Asian cast that includes the part-Bengali Paul Bhattacharjee as Benedick and Meera Syal as Beatrice. The cast needed a voice coach to make them sound authentically “Indian”.

The costumes, including the suits, saris, lungis, jeans and even T-shirts, have been done by Delhi-based designer Himani Dehlvi, whose father was the artist Tyeb Mehta.

|

| Anjana Saha (centre) with Anmol Hoon, a student of Delhi Public School, New Town, and Janardan Ghosh, a drama teacher at Apeejay School |

Audiences are made to feel they have stepped into India as soon as they enter the Courtyard Theatre, “with its awnings and stalls, (live) Indian music and a large tree dominating the stage”. The foyer resembles an Indian bazaar where images of the Bard adjoin those of someone who probably considers himself to be even more famous — the Badshah of Bollywood, Shah Rukh Khan

Himani, who has worked for films such as Monsoon Wedding and The Bourne Supremacy, had to make four trips to Stratford to fit the 21-strong cast and five musicians. She recalls the first night buzz: “People came out dancing — there is a lot of energy in the show. Shakespeare adaptations work well because his morality fits in quite well for India.”

After the play’s run in Stratford ends on September 15, it transfers to the Noel Coward Theatre in London’s West End for performances from September 22 to October 27.

The play’s British Asian director, Iqbal Khan, says: “What this shows is that Shakespeare wrote for the street, he wrote for everyone. I would love to take this all over the world and especially to India.”

Much Ado About Nothing is part of a much grander plan by the RSC to rediscover the relevance of Shakespeare in the modern world. Ever since 2005, when Britain won the bid to stage the Olympic Games in London in 2012, detailed planning has been undertaken to put Shakespeare at the heart of the “cultural Olympiad”.

Over the past year, Shakespeare plays have been brought to the UK from Russia, the United States, Iraq, Brazil and many other countries.

Jacqui ’ Hanlon, the RSC’s director of education, describes the Shakespeare project: “It’s huge. There is a massive piece of work globally looking at how Shakespeare is the world playwright — or testing that assumption. We see so much passion and ownership for Shakespeare in communities and cultures across the world.”

She confirms that foreign teachers such as Anjana are expected to return to the UK for an international conference on Shakespeare from September 6-8.

The foreign visitors have received a warm welcome from the RSC’s outgoing artistic director, Michael Boyd, who believes the idea of theatre is “to bring in the full human presence. Hollywood is desperately trying to achieve three dimension — theatre has it for free.”

Anjana seems to be an inspirational teacher in the first place but being in Stratford has made her even more enthusiastic about talking Shakespeare back to her pupils in Calcutta.

She tells t2: “Very often I face that question, ‘Why Ma’am, why must we study Shakespeare? He’s long gone. We find the language so difficult with old English words like thou.’ But being here has helped me come closer to Shakespeare and to understand he was talking about love, relationships, anger, jealousy, ambition, competition — things my children can relate to very easily in today’s context.”

“Another thing they are encouraging us to do at the workshop is they want us to introduce the local flavour — marry Shakespeare to our music, our heroes, our role models and give him a new lease of life by connecting him to our culture,” says Anjana.

There are two others who have come from Calcutta with Anjana — her 17-year-old pupil, Anmol Hoon, and Janardan Ghosh, a “cultural coordinator and drama teacher” at the Apeejay schools on Park Street and in Salt Lake.

Janardan poses the question: “How would Macbeth react if he had a Bengali origin? It might be the same lines, the same words but we definitely react differently (from Europeans). What I find interesting here (in Stratford) is the process — how you are dealing with a difficult and alien topic for a new generation in a more accessible way. How do you reach the children?”

Of all the students gathered for the workshop, Anmol, who has clearly been bitten by the acting bug, comes across as the most confident. “The whole thing about getting into theatre was my father’s idea — he is in advertising,” reveals Anmol.

Given a choice of roles, he would love to be Touchstone in As You Like It because as a court fool “he can literally say anything”.

Anjana has an observation about A Midsummer Night’s Dream which was the homework set for the overseas teachers: “We tried to find links with Bollywood and that connects the teachers and the students. We tried to discover common motives — I said this is about star-crossed lovers and love being blind and the complications arising out of mismatched partners. Well, all this is true of a Bollywood film.”