Book: Learning To Talk

Author: Hilary Mantel

Publisher: Henry Holt and Co

Price: $19.99

The first two books of Hilary Mantel’s acclaimed Cromwell trilogy made her the first British woman writer — she died last month — to win the Booker Prize twice (2009, 2012), but her talents are not restricted to historical fiction. First published in the same year as her memoir, Giving up the Ghost, Learning to Talk (2003), the book has been reissued this year. The volume brings together six short stories written over several years that draw upon the author’s difficult childhood and explore the unsettling complexities that lie at the heart of memorialising the past.

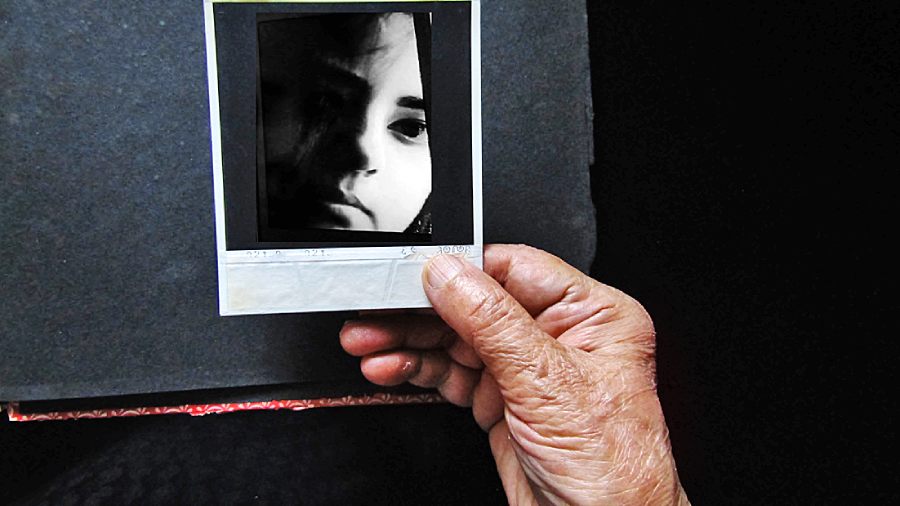

Mantel describes these stories as “autoscopic”, as though the author were looking at a doppelgänger “but that double had a slightly different story”. Mantel’s sinewy prose, however, resists the maudlin charms of nostalgia. Each story is tightly focused upon a particular experience, all told by grown-ups in the first person in retrospect. Each combines a rambling style with a curiously timeless, yet tightly controlled, chronology. Each deals with a distinct stage of growing up and reveals concerns that are at once universal and unique.

It is commonplace to say that youth can only be described by the no-longer-young. All the stories, including “King Billy is a Gentleman” (New Writing, 1992), enact this platitude in compelling prose. “I cannot get out of my mind, now, the village where I was born, just out of the curl of the city’s tentacles,” begins the narrator. It is only at the end that we realise that this insistence of the past, so long ignored by the successful lawyer eager to dissociate himself from his upbringing, is triggered by the news of a death in a neighbour’s family, received several years too late. The impact of so-called inconsequential people upon us and the failure of good fences to keep out their shadowy presences from haunting our present shapes this impeccably-crafted description of Irish immigrant experience.

Making sense of growing up acquires deeper poignancy in “Destroyed” (Granta 63, 1998). When the mother talks about the impossibility of anything ever being a substitute for anything else but acts out substitutions all the time, both the adult narrator and her child self are baffled. In “trying to work it out”, we are offered “a different story, about some dogs, which perhaps relates to it. If I offer some evidence, will you be the judge?” The evidence is a glorious mess of stepfathers and stepbrothers and “step dogs” and same-named cousins and aunts and X years of pulling back (since “in the case of numbers it is allowable to make a substitution”) and the slow-burning sadness of destroyed love.

The nine-year-old experiencing “Curved is the Line of Beauty” (TLS No. 5157, 2002) reiterates the undependability of grown-ups: “every adult throat bubbled, like a garbage pail in August, with the syrup of rotting lies.” Remembering her first encounter with the word, ‘coloured’, in the context of human skin (“don’t say ‘Jacob is black’, say ‘Jacob is coloured’. What, coloured? I said. What, striped?”), the narrator shapes her family visit to a mixed-race household in terms of a box of crayons and the colour of momentary but momentous friendships. A deep concern with human tendencies to malign the different also informs the most astringent of the stories: the titular “Learning to Talk” (London Magazine, 1987). The reminiscer brings waspish wit to bear upon social discrimination: “people were not supposed to worry about their accents, but they did worry, and tried to adapt their voices — otherwise they found themselves treated with a conscious cheeriness, as if they were black, or bereaved, or slightly deformed.”

Along with ghost selves and the cruel tyranny of social and religious prejudices, the stories are held together within the frame of maternal influence. This is most obvious in “Third Floor Rising” (The Times Magazine, 2000) and “The Clean Slate” (Woman & Home, 2001). The eighteen year old in the former, starting on her first job at the department store of which her mother is a favourite employee, is blissfully unaware of the “true ghost story” that becomes symbolic of the desperately squalid lives of working-class women. The young woman in the latter visits her mother on her deathbed in an urgent bid to document the family tree. She likes “to be free, so far as [she] can, from the tyranny of interpretation” and is exasperated by her mother’s inventive mnemonics. The most unreliable of the narrators, her fixation with facts and figures ironically reveals her to be her mother’s daughter after all.

“An unhappy childhood is a treasure for a writer,” says Mantel in an interview. This luminous volume re-establishes Hilary Mantel as an author whose aesthetic command of the riches of her own history is no less sure than her grip on Cromwell’s England and completely justifies the new edition.