Sunday, 15 February 2026

Sunday, 15 February 2026

Sunday, 15 February 2026

Sunday, 15 February 2026

A barracks-style detention center in Louisiana is jammed with around 90 immigrant women, mostly workers without legal documentation from Central and South America, sharing five toilets and following orders shouted by guards.

There is also, among them, a Russian scientist.

She is 30 years old, shy and prone to nervous laughter. She cannot work, because her laptop was confiscated. She plays chess with other women when the guards allow it. Otherwise, she passes the time reading books about evolution and cell development.

For nearly eight weeks, Kseniia Petrova has been captive to the hard-line immigration policies of the Trump administration. A graduate of a renowned Russian physics and technology institute, Petrova was recruited to work at a laboratory at Harvard Medical School. She was part of a team investigating how cells can rejuvenate themselves, with the goal of fending off the damage of aging.

On Feb. 16, customs officials detained her at Logan International Airport in Boston for failing to declare samples of frog embryos she had carried from France at the request of her boss at Harvard.

Such an infraction is normally considered minor, punishable with a fine of up to $500. Instead, the customs official canceled Petrova’s visa on the spot and began deportation proceedings. Then Petrova told her that she had fled Russia for political reasons and faced arrest if she returned there.

This is how she wound up at the Richwood Correctional Center in Monroe, Louisiana, waiting for the U.S. government to decide what to do with her.

Petrova’s case is being watched by thousands of young, highly educated Russians who, like her, fled the country after Russia invaded Ukraine. It has also caught the attention of prominent figures in Russia’s political opposition who warn that, for the United States, delivering a dissident scientist to President Vladimir Putin would be crossing an especially foreboding line.

For her part, Petrova is seeing the United States from a new and unsettling vantage point. “I feel like something is happening generally in America,” she said, in an interview over a video link. “Something bad is happening. I don’t think everybody understands.”

Immigration and Customs Enforcement has twice refused her lawyer’s petition for parole, contending that she is a flight risk and a threat to U.S. security. Petrova sometimes mentally rehearses what she would do if she were, in fact, deported to Russia. She cannot say for sure when or if she would be arrested, she said, but the threat of political repression would always be present.

“This is the problem of this kind of autocratic regime — the people who stay there are kind of hostages,” she said. “That is the fear of being there. You don’t know what will happen. You don’t know if they will come for you or they won’t.”

Harvard has made little comment about Petrova’s detention. A spokesperson said this week that the university “is closely following the rapidly shifting immigration policy landscape and the implications for its international scholars and students,” and is “engaged with Ms. Petrova’s attorney on this matter.”

Many in the research community there only learned about it two weeks ago, when Petrova’s co-workers started a GoFundMe appeal to help pay her legal expenses. The news sent shudders through a community of scientists who immigrated to the United States for careers in research. It comes amid deep cuts in federal funding for science that, to many, signal that a period of openness and progress may be ending.

Petrova is not giving up on her work. As she awaits her hearing, she is studying meiosis, a type of cell division that allows egg and sperm cells to reset epigenetic marks, pointing the way to possible strategies to stop aging. All she can think of is getting back to her laboratory.

“I was in paradise,” she said. “I would very much like to stay in paradise.”

A ‘Supernerd’

Petrova had just finished her master’s degree when Konstantin Severinov, a prominent molecular biologist, recruited her for an ambitious, high-profile project in Moscow.

Severinov, who leads a laboratory at Rutgers University in New Jersey, had been asked to design a Russian genome-sequencing center, backed with $250 million in funding from Rosneft, the state-owned oil company. He was assembling a team to help build a database structure and write code.

He described Petrova as a “supernerd,” the product of especially intense, competitive scientific training. Her skills, which combined computer science and biology, were “very, very marketable,” he said in an interview, in demand at genomics centers all over the world.

Severinov wanted her on the team, he said. The job was interesting scientifically and “highly advantageous financially.” But it required passing a security clearance, he said, and Petrova would not promise to stop supporting Russia’s political opposition. He ended up hiring her as an outside consultant.

“She turned out to be a principled person who just would not bow,” he said.

Severinov was, at times, frustrated by her impracticality — “you can call it childish, you can call it principled, you can call it different ways,” he said.

“I would say, among many young scientists, there are some which are very, very career-oriented — in a good way,” he said. “They know what needs to be done to promote themselves. She is not of that kind. She is, in a way, like a daydreamer. She is different.”

She was raised by two engineers — her mother a specialist in radio communications and her father a computer programmer, said Vladimir Mazin, a close family friend. He described Petrova as a “passionate scientist” who, on vacation in the countryside, carried her laptop with her to breakfast and dinner so she could continue training neural networks, a type of machine learning.

“Kseniia is one of those people who are truly interested in obtaining new knowledge, in finding out something that hasn’t been known before,” he said. “That’s what she is interested in. Everything else is secondary.”

In her late teens, she supported the opposition-minded Russians who took to the streets to oppose Putin’s return to the presidency. Then she began joining them. Petrova made no secret of her views; she recalled being asked, in the job interview for the genomics center, to promise she would not post criticism of Putin on social media. She refused.

“I think in each country, scientists are opposed to autocratic government,” she said.

On Feb. 24, 2022, when Putin sent columns of Russian tanks across the border into Ukraine, Petrova joined protests that surged through Moscow’s streets. On March 2, she was arrested, charged with an administrative violation, fined about $200 and released.

It was clear that things were changing quickly, Petrova said. The handful of news sources she relied on for objective information “closed immediately,” she said. Petrova feared the border would close as well. She left the country two days later.

She said that after this, it became “really obvious” that if she wanted to be a scientist, she had to leave: “I changed my decision from ‘I will never leave Russia’ to ‘I am leaving Russia immediately.’”

Many of her classmates left at the same time. Some found lucrative jobs writing code for banks or private companies. Petrova had an offer from a lab in Britain. But she was looking for something particular — “the kind of science,” as she put it, “that I would call beautiful.”

Welcome to the Frog Palace

Leon Peshkin, a principal research scientist in Harvard’s department of systems biology, had been looking to hire someone for a year.

The Kirschner Lab, where Peshkin works, is investigating the earliest stages of cell division. These changes are easy to observe in the eggs of the xenopus frog, which are large and hardy. To lure Marc W. Kirschner to Harvard, the university constructed a vast aquarium where females bob in circulating water, known internally as the “frog palace.”

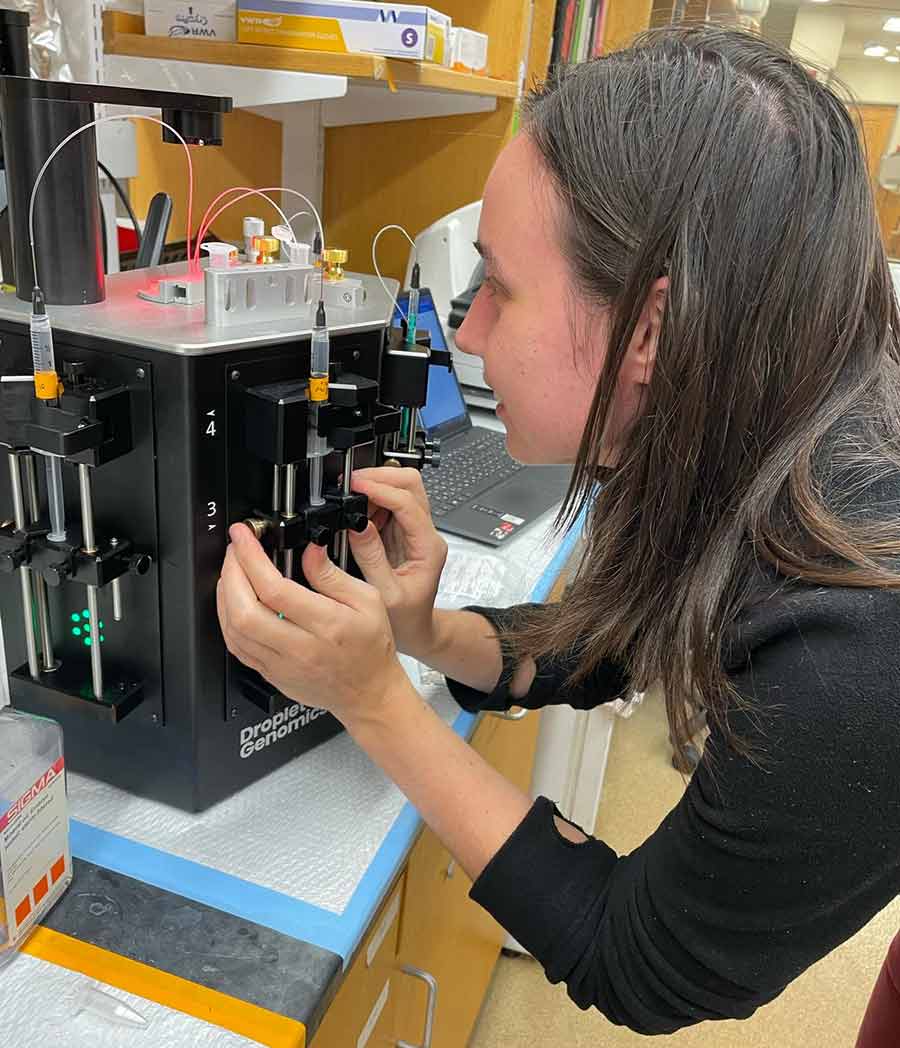

Peshkin’s team is interested in sperm and egg cells, and how they repair damage as an embryo develops. They needed someone equally fluent in machine learning and cell biology, Peshkin explained in a post on Kaggle, an online community for data scientists. Petrova reached out.

When she arrived in Boston in May 2023, Peshkin was shocked to discover that she had not brought a suitcase; she carried a backpack. It became clear, he said, that she was “extremely ascetic,” entirely wrapped up in her research.

“I thought the Russia of my childhood was gone, the Russia of this crazy, dedicated, ascetic scientist is gone,” he said. Over the months that followed, Peshkin watched her focus intensely for many hours; he saw what she could pull off in a few days of coding. “She is probably strongest I’ve seen,” he said. “I am at Harvard for 20 years.”

Petrova found ways to speed up everyone’s work. In a dark, enclosed room with a laser-based Raman microscope, William Trim, a postdoctoral fellow, spent his days examining the migration of lipids through tissue.

He painstakingly noted his findings by hand, a task that could take up to two hours each day. “You don’t need to do that,” he said Petrova told him. She wrote him a script that did the job in seconds. “Any problem I have with data, she has a solution,” Trim said. They became close friends, and he eventually offered her a room in his apartment.

“All she did was science,” he said. “She would be coming home at 1 a.m. sometimes, because she just spent all day — 14, 15 hours — tweaking the flow rates of five tubes that all coalesce into one place to get this cell into a droplet.”

Peshkin worried she would burn out. He was relieved when she told him she was taking a vacation to France, where pianist Andras Schiff was giving a concert. She bought theater tickets and planned trips to see friends from Moscow, now scattered across Europe.

She would also make time for work. Peshkin collaborates with a laboratory in Paris, where one of the scientists had figured out how to slice superfine sections of a frog embryo.

No one at Harvard knew how to do it; high-quality samples would substantially speed up their work. A few times, their French colleagues had tried to mail the embryo samples, but they thawed in transit and arrived too damaged to use.

“I said, ‘Well, you’re there,’” Peshkin said. “Why don’t you get this package?”

A Shift in the Atmosphere

Petrova’s return flight from Paris landed in Boston on the evening of Feb. 16. As the plane sat on the tarmac, she texted back and forth with Peshkin, trying to confirm how she should handle the package in customs. But by then, the passengers were already filing off the plane, he said, and Petrova cut short the conversation.

At first, Petrova said, her reentry felt normal. At passport control, an officer examined the J-1 visa that Harvard had sponsored, identifying her as a biomedical researcher. The officer stamped her passport, admitting her to the country.

Then, as she headed toward the baggage claim, a Border Patrol officer approached her and asked to search her suitcase. All she could think was that the embryo samples inside would be ruined; RNA degrades easily. She explained that she didn’t know the rules. The officer was polite, she recalled, and told her she would be allowed to leave.

Then a different officer came into the room, and the tone of the conversation changed, Petrova said. This officer asked detailed questions about the samples, Petrova’s work history and her travel in Europe. The official then informed Petrova that she was canceling her visa and asked her whether she was afraid to be deported to Russia.

“Yes, I am scared to go back to Russia,” she said, according to a Department of Homeland Security transcript provided by her lawyer. “I am afraid the Russian Federation will kill me for protesting against them.”

Petrova’s attorney, Greg Romanovsky, said that Customs and Border Protection had overreached its authority by canceling her visa. He acknowledged that she had violated customs regulations but said it was a minor offense, punishable by forfeiture and a fine.

To cancel her visa, Romanovsky said, the agents needed to identify grounds for excluding her. “There are many, many grounds of inadmissibility, but violating a customs rule is certainly not one of them,” he said.

Lucas Guttentag, a professor at Stanford Law School, reviewed documents in the case and agreed. He said that Petrova had been legally admitted to the United States, and then “the government itself created the alleged improper immigration status that is now the basis for her detention.”

“Subjecting anyone to this process is wrong, and this case is both shocking and revealing,” said Guttentag, who served as a senior Justice Department adviser under President Joe Biden and senior adviser to the DHS during the Obama administration.

A spokesperson for the DHS, asked why Petrova’s visa had been canceled, said that a canine inspection found petri dishes and vials of embryonic stem cells in her luggage without proper permits.

“The individual was lawfully detained after lying to federal officers about carrying biological substances into the country,” the spokesperson said. “Messages on her phone revealed she planned to smuggle the materials through customs without declaring them. She knowingly broke the law and took deliberate steps to evade it.”

When the Border Patrol agent canceled Petrova’s visa, she became an immigrant in the country without legal permission, among the thousands detained since Trump took office. She was sent to the Richwood Detention Center to await a hearing in which she will present her case for asylum to an immigration judge.

“If she wins, she will not be deported,” Romanovsky said. “If she loses, she will be deported to Russia.”

He has also filed a petition for her release in federal court, and pressed ICE to release her on parole. “I am basically pleading for mercy,” he said. “In a different environment, I think she would have been out a long time ago.”

Petrova has spent the last month in a dormitory lined with rows of bunk beds. It is cold, and at night, the women sometimes shiver under thin blankets. Once a day, they are allowed an hour outside. Breakfast comes at different times, sometimes as early as 3:30 a.m. The hardest thing, she said, is the constant noise. The facility’s psychiatrist gave her earplugs to help her sleep.

Unable to work, she observes the women around her. Around half are Latin Americans in their 30s and 40s who crossed the border for economic reasons, she said. A second group is made up of Asians and citizens of former Soviet states, who crossed the border legally, seeking political asylum.

None of them deserve to be held under these conditions, she said. “I thought this was impossible, to be in this situation,” she said. “Even immigrants here, they have to have some rights. But it seems that nobody really cares about our rights here.”

It has challenged the view of America that she formed in Russia. “This is not the kind of America I used to know,” she said.

An Empty Bench

Petrova’s things are still scattered around the laboratory at Harvard — a flower garland, a sleeping bag, a guitar. Before she went on vacation, she programmed a drip irrigator to water the plants on her window sill, and once a day, for five minutes, it whirs into action.

Her colleagues are distracted and anxious; work in the laboratory has stalled. When Peshkin made the rounds of Harvard laboratories, asking colleagues to send letters of support for her to ICE, many of them confessed that they were afraid to put their names on paper — because they were in the country on temporary visas as well.

“Something has happened to the fabric of society,” he said. “Something is happening.”

Worry about her case has also radiated across networks of Russian emigres and scientists.

“She is an indicator that the world is becoming almost evil and dangerous for people who are homeless and mean no harm to anyone,” said Severinov, the biologist who recruited Petrova in Russia. “It is an irony that this is becoming so on both sides of the pond.”

Marina Sakharov-Liberman, the granddaughter of Soviet physicist and dissident Andrei Sakharov, has been following the case from her home in London. She said it was “extraordinary” that Harvard had not more publicly protested Petrova’s detention and demanded her release.

“That is something that I would expect in Russia,” she said. “Everyone would be afraid. If someone was ‘disappeared,’ the institutions would be silent. Very few people would raise their voices and risk their positions.”

No one at Harvard feels worse than Peshkin. Again and again, he has asked himself why he allowed Petrova to take the risk of carrying the samples. He rereads the text exchange he had with Petrova while she was sitting on the plane.

“I mean, anybody in my place would say, ‘Please don’t take the box,’” he said.

Petrova does not blame Peshkin. She does not even complain much about life in detention. If she had access to a laptop, and could analyze data from her laboratory at Harvard, “it would be good enough,” she said.

But she worries that, when this is all over, she will no longer be able to work at the same level. “Even if I am released, I will feel myself much less safe,” she said. “Of course it will affect my efficiency. I will be very afraid. What if I get rearrested?”

The New York Times News Service