|

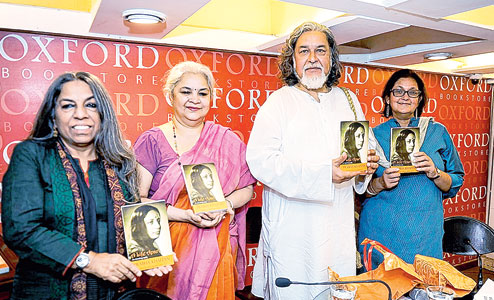

| Urvashi Butalia, Ira Pande, Kalyan Ray and Namita Gokhale at the launch of A Life Apart (Rashbehari Das) |

Four months after its official unveiling at the Jaipur Literature Festival, the English translation of the late Prabha Khaitan’s autobiography was launched in the city she loved and lived in, Calcutta.

A Life Apart, translated from the Hindi Anya se Ananya by Ira Pande and published by Urvashi Butalia’s Zubaan Books, has been summed up beautifully by author Namita Gokhale in her foreword: “Sometimes it cuts too close to the bone for middle class comfort, unsettling the safety net and entitlements of complacency and convenience.”

Urvashi, Ira and Namita were present at Oxford Bookstore, Park Street on Friday evening. The trio hadn’t known Prabha Khaitan personally, they were now trying to know Calcutta through her eyes, they said. A fourth woman, who knew Prabha well and had held profound discussions with her about life, womanhood and the universe, was kept away by ill-health. To fill in for her, Aparna Sen sent husband Kalyan Ray, who aptly described Prabha as “not a woman cut out of the mold.”

|

| Nicholas Roe and Malabika Sarkar at the launch of John Keats. (Sanat Kumar Sinha) |

Apt because this girl of the well-known Khaitan family of Calcutta bucked convention at every step, be it joining Presidency College, going to America, starting her own business or falling in love with a married man. Born in 1942, Prabha Khaitan was a businesswoman, author, translator and social activist. But A Life Apart also reveals how this confident trailblazer was racked by low self-esteem, how her attraction for the married and father-of-five Dr Saraf later turned into a nagging need and how love transformed into revulsion.

Butalia, who has been a feminist publisher for 30 years, moderated a lively discussion between Ira and Namita. But this being Calcutta, the audience soon joined in. Speaking about the tough job of translating Hindi to English, Ira spoke about the hierarchy of languages.

“Hindi is not the language of the empowered,” she said, giving examples like dukhiari nari. Namita agreed. The subtext of victimhood, she said, is written into Hindi. Urvashi asked authors Nabaneeta Dev Sen and Bani Basu, who were sitting in the audience, if that was the case with Bengali too. “Far from it,” laughed Nabaneeta. Namita also spoke about the autobiography’s comic element. “The passages in America are so, so, so funny!”

The audience, which included Prabha’s foster son Sundeep Bhutoria and daughter-in-law Manjari Maheswari, had many questions about languages, the tricky art of translation and Prabha’s life.

A question that is bound to pop into many people’s mind after reading A Life Apart was voiced by Nabaneeta: “I just have one question — why Dr Saraf?” All three women on the dais nodded in agreement. That the lion-hearted Prabha would submit to, seek and crave this rather cowardly and selfish man is quite unthinkable, was the general opinion. But as we all know, the heart works in strange ways!

Ode to Keats

|

| Bani Basu and Nabaneeta Dev Sen |

Was John Keats really “a pale flower” that Victorians believed him to be or was it a myth invented by Shelley’s elegy Adonais and sustained right down to Jane Campion’s 2009 film Bright Star? Nicholas Roe, chair of the Keats Foundation, Keats House, Hampstead, and professor of English literature at the University of St. Andrews, feels it’s answer No. 2.

At a discussion on his recent biography titled John Keats at Oxford Bookstore with Presidency University vice-chancellor Malabika Sarkar, herself a specialist on the Romantic age, Roe urged for a reassessment of the life of the poet, perceived to be of overly delicate health and sensitivity.

To prove his point, Roe has explored Keats’s growing-up years in London’s northern outskirts. “His favourite sport was prize-fighting, or bare-knuckle fighting. It was illegal in London but drew hundreds to the city fringes to watch stars like Jack Randall fight. Young Keats was forever looking for sparring partners in school,” said Roe.

Later he would measure his poetic capabilities in boxing terms, walking around the Lake District and Scotland to improve his “reach” as a poet, which in boxing means making contact with the opponent.

“His walking tour covered at least 600 miles. That suggests he was strong as an ox then,” Roe pointed out.

Though it is Coleridge and De Quincey who are known for opium addiction, Roe suggests that Keats too was under its influence at one point. “Fanny Brawne, his girlfriend, dosed herself with laudanum (opium in alcohol). Opium was the only pain-killer in those times and when his brother Tom contracted tuberculosis in 1817, I think Keats was giving him opium. He too started taking it to ‘keep up his spirits’, as surmised by his friend Charles Brown, who warned him of the danger of such a habit.”

But Roe claims Keats continued even after Tom died, into the magical spring of 1819, which produced his greatest works.

That is why he contends that Ode to Indolence is the first in the sequence of his great odes and not an afterthought, as is believed.

And why did Keats get on well with Fanny, asked Sarkar. “Because they were both the same height and saw eye to eye. Other women looked down on him,” said Roe of the five-footer poet, drawing teeters from the gathering.