A neurodivergent individual can crack a joke, be in a relationship, and teach important life lessons.

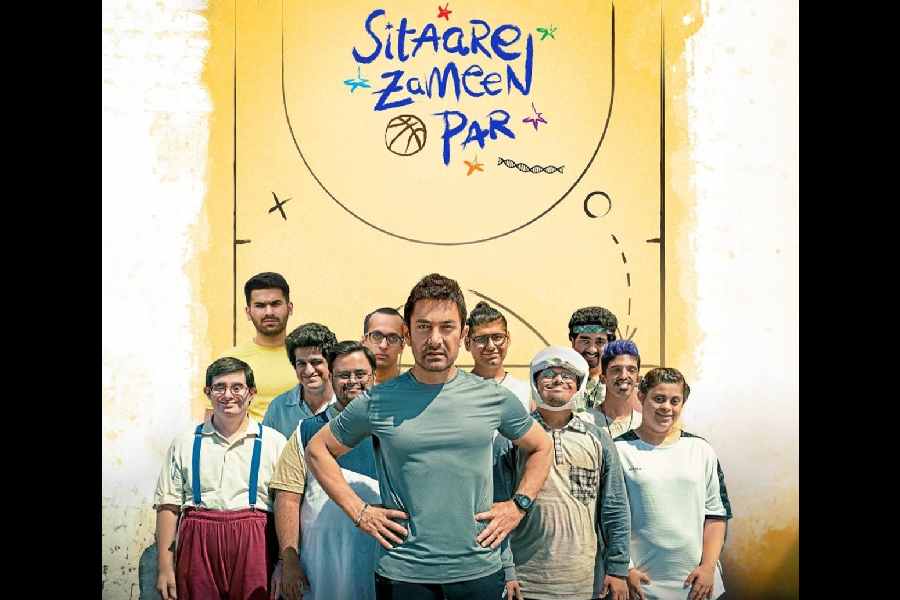

The Aamir Khan-starrer Sitaare Zameen Par, released earlier this year, struck a chord with parents, educators, and disability rights activists and continues to spark conversations.

The film has become a talking point for its sensitive portrayal of individuals with disabilities, creating awareness and promoting inclusivity in a society still grappling with acceptance.

“A mainstream Bollywood film has far more reach than any academic seminar,” said Amita Prasad, director of Manovikas Kendra, a centre for individuals with disabilities.

Its relevance extends well beyond its screening dates, those working in the disability sector said.

For many, the film offers a mirror to people’s attitudes.

The mother of a 14-year-old with autism said it captures societal insensitivity. “Calling names is common. People don’t realise how hurtful it is, our children are sensitive to that,” she said.

What sets the film apart is its tone. The message of respecting diversity is conveyed in a light-hearted, humorous way, avoiding the pitfall of being overly preachy.

Reena Sen, vice-chairperson of the Indian Institute of Cerebral Palsy, praised the choice of adult protagonists with disabilities, a rare sight in mainstream media.

“We see adults with disabilities portrayed with their strengths and limitations. The film brings out their personalities. You see them as people first, not as labels,” she said.

The film follows a group of individuals with disabilities who connect with a bad-tempered coach through basketball. But it’s not just about learning a sport. “It’s about adapting: how society must change its mindset, not expect neurodivergent individuals to fit into a rigid mould,” Sen said.

That perspective resonates with many disability advocates who have long demanded that individuals with disabilities be seen as equals.

“The film challenges the notion that they are somehow ‘less’. It shows that they have feelings, they can fall in love, and want companionship, just like anyone else,” said Sudeshna Chowdhury, principal of Bhabna, a school for children with special needs.

Chowdhury also pointed out a persistent societal misconception: “There’s this belief that our children don’t have sexual urges. These

stereotypes need to go.”

Chowdhury emphasised that the film is not only for those directly affected by disability.

“It’s the neurotypical audience that needs to watch this most,” she said. “Understanding must come from all sides.”

One of the film’s most poignant takeaways is when the neurodivergent characters choose to celebrate someone else’s success over winning. For Prasad, this challenges the dominant cultural obsession with competition.

“It’s a message to all parents: your child’s humanity is more important than their rank,” she said.

In response to the film, many institutions arranged screenings for students. Modern High School for Girls took 36 psychology students from Classes XI and XII to see it.

Pradipta Kanungo, director of Bloomingdale Academy High School, which follows an inclusive education model, also took her students.

“The mainstream needs to see this. There are so many unfounded biases about those with special needs,” she said.

Her school began with a 50:50 ratio of children with and without disabilities. Today, due to hesitation from parents of neurotypical children, that ratio has shifted to 30:70 — a telling sign of the societal gap the film seeks to bridge.

Sumitra Paul Bakshi, founder of the organisation Dwish, agreed. “The real shift will happen only when more neurotypical children grow up with an understanding of what inclusion really means,” she said.