When Soumendu Roy was being wheeled in on a chair at Nazrul Tirtha, a film show had just got over and the audience was on its way out. But none recognised the man who had wielded the camera in milestone movies like Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne, Sonar Kella and Shatranj ke Khiladi.

“This is so disturbing,” remarked Reshmi Chatterjee of Halo Heritage, the organisation that was felicitating Satyajit Ray’s cinematographer.

The man, who will turn 84 on February 7, was the cinematographer for 21 of Ray’s films, including 15 features, other than working with Tapan Sinha, Tarun Majumdar and M.S. Sathyu.

Introducing him to the gathering, Arindam Saha Sardar, who has made a documentary on the three-time National Award winner, pointed out that though Roy’s Ray connection started with Pather Panchali where he worked as a trolley and reflector assistant to Subrata Mitra, his first independent work with the master was a Tagore documentary in 1960 which the central government had commissioned Ray to do to mark Tagore’s birth centenary the year after. Ray also wanted to make a film on Tagore’s short stories, which Mitra was to shoot later that year. “During the shooting of Teen Kanya, Mitra developed an eye problem and Ray turned to his assistant to take over. That was the start of their long association.”

Saha Sardar met Roy in 2006 after the latter liked a documentary film he had made on the Singur agitation. “When I wanted to learn camera work from him, he said most people who came to him found his school of realism tough to stick to but agreed to let me accompany him at work,” said Saha Sardar, who later shot the making of Mrinal Sen, the last documentary Roy supervised the camera for, in 2013.

Picture courtesy: Jibonsmriti Digital Archive, Uttarpara

Atanu Pal of Third Eye, a photography group, spoke of Roy's enthusiasm for black and white photographs. “In those days, Eastmancolor still had not come and Ray insisted on using colour only when absolutely needed. In the last scene of the black and white Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne, when Goopy and Bagha, wearing their magic shoes, clap to reach Shundi, the place they reach is a land of dreams and hence is shot in colour.”

Pal pointed out that the black and white combination also leaves much to the imagination. “You will never know what shade of clothes a person is wearing and can only guess from the tone. When Ray did Ashani Sanket, again with Soumenduda on the camera, he shot it in colour. The decision raised eyebrows as people had expected a story of famine to be told in black and white. But Ray felt that he could establish the aridity of famine more starkly in colour, leaving nothing to the imagination.”

Adinath Das, former dean and academic head at Satyajit Ray Film and Television Institute, expressed amazement at the effects Roy achieved despite the limitations under which films were made in those days. “They had to work with 50 ASA or 100 ASA stocks. (The slower the film speed the greater the image detail but slower film speeds also meant difficulty to shoot in low light.) Today we have 400 or 800 ISO stocks (which make it easier to shoot in low light). And if you shoot in digital mode, you have more flexibility. But they had to wait with their hearts in their mouths for the roll to come back from the laboratory to know what the results were.”

Towards the end of Ashani Sanket, there is a scene where the actress stands near the door with her back to the twilight sky as the sun sets behind her. “The heroine’s face was in midshot. Even with the aperture fully open, Roy thought the negative would be underexposed but Ray asked him to go ahead. We have heard how he extracted satisfactory result after speaking to Gemini Colour Lab in Chennai.”

He cited another instance of how they innovated. “Even the GE (photography light) meter came much later. Roy used a home-made soft box made of photo flood lamp which his guru Mitra had devised. Now we refuse to budge without packing two trucks of lighting equipment. Interactive machines tell us how much light is needed where. We have a problem of plenty. Our eye does not get trained to read gray shades. We do not learn to respect light.”

He challenged the perception that Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne was a children’s film. “It's an anti-war film and has extraordinary graphical symbolism. We need to study it frame by frame to extract the nuances. The jingoistic king of Halla, for example, is presented in black and gray tones. The lighting is low key. The light source in the cave-like set is limited, through slits on the walls. Shundi is good and hence is presented in high key — soft light, with a lot of white. It was a challenge for Roy to distinguish between background and foreground as Santosh Dutta wore white and the palace interiors were white as well.”

Roy was felicitated by Hidco chairman Debashis Sen. Being unwell, the octogenarian did not speak. But the audience got to hear him discuss his craft thanks to Saha Sardar’s documentary on him which was screened at the end.

.jpg)

SHOT BY ROY

• Teen Kanya (1961)

• Abhijaan (1962)

• Palatak (1963)

• Abhoya O Srikanta (1965)

• Baksabadal (1965)

• Mahapurush (1965)

• Kapurush (1965)

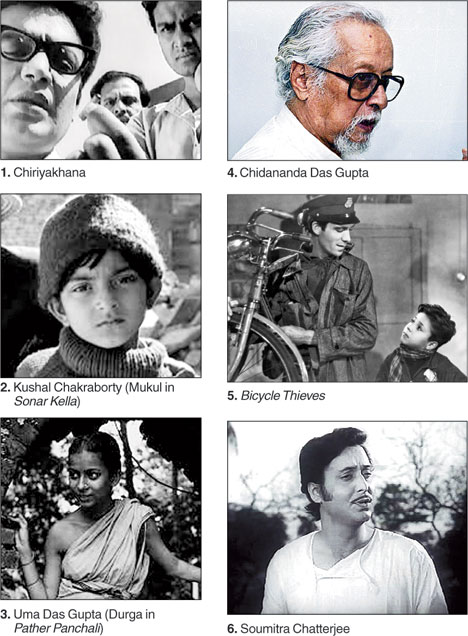

• Chiriyakhana (1967)

• Balika Badhu (1967)

• Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne (1969)

• Aranyer Din Ratri (1970)

• Pratidwandi (1970)

• Kuheli(1971)

• Seemabaddha (1971)

• Ashani Sanket (1973)

• Sonar Kella(1974)

• Jana Aranya(1976)

• Satranj Ke Khilari (1977)

• Joybaba Felunath (1979)

• Heerak Rajar Deshe (1980)

• Sadgati (1981)

• Phatik Chand (1983)

• Piku (1983)

• Ghare Baire (1985)

The list is not exhaustive

Do you have a message for Soumendu Roy?

Write to The Telegraph Salt Lake, 6 Prafulla Sarkar Street, Calcutta 700001 or email to saltlake@abpmail.com