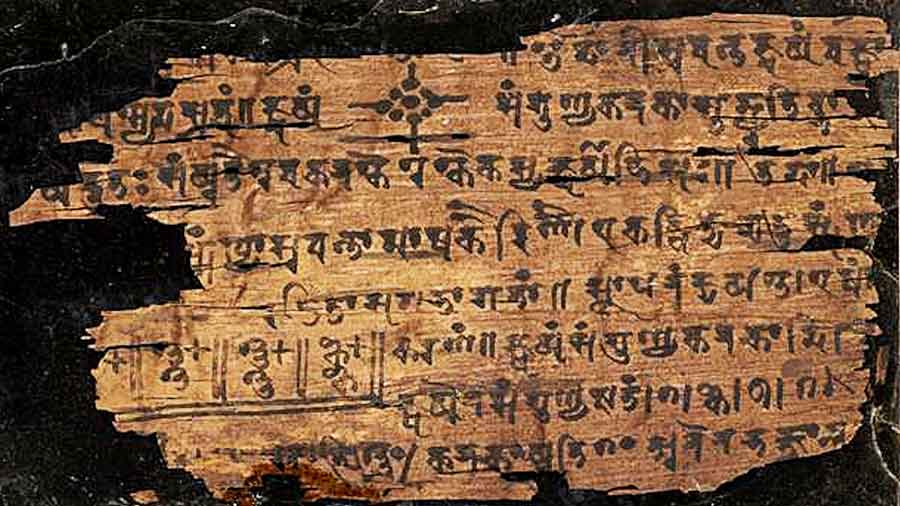

Kautilya’s Arthashastra,an ancient Indian political treatise lost in the sixth century,changed our understanding of classical Indian politics after it was rediscovered by R. Shamasastry in 1905 in Mysore. There are numerous unpublished manuscripts in Sanskrit,Pali, Persian, Arabic as well as in all regional languages that provide language federalism in India. Some are kept at public institutions like the National Library in Calcutta, the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Pune, and the Oriental Research Institute at S.V. University, Tirupati. Many of these are in possession of individuals and families, for instance, in Chowk and Gopal Mandir Gali in Varanasi.

One remarkable instance is that of Sri Annamacharya, the saint-poet(1408-1503). He wrote close to 32,000 keertanas. The poet’s son, Peda Tirumalacharyulu, and grandson,Chinna Tirumalacharyulu, had them written and had them etched on copper plates. The process used for etching on these thick plates, some weighing around 40 kilogrammes, remains a mystery. This is just one of the multifarious unique uses of the large reserves of copper in the southern part of Andhra Pradesh. These plates were finally recovered, and 13,736 keertanas are estimated to have survived.The keertanas were later published by the Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanam. They are now available in Unicode in a searchable formaton www.andhrabharati.com, a website designed and maintained by private individuals, such as Vadapalli Seshatalpa Sayee with the support of friends.

In addition to these projects, the government can formulate a clear policy towards these unpublished manuscripts in particular and India’s past in general. This is necessary as modern India’s relationship with its past is unique. Nations in the West have disinherited their past. This is clearly stated by the Orientalist and scholar, Ernest Renan. Referring to the nations in the West, he said, “To forget and — I will venture to say — to get one’s history wrong are essential factors in the making of the nation.”

In contrast, Indian national leaders across the spectrum have recalled different accounts of the past to claim India’s Independence. Independent India must formulate a straightforward, multi-dimensional,inclusive policy towards its past. A visible past can give greater clarity to modern India.

In the context of this uniqueness,a clear policy about one aspect of the past — namely, unpublished manuscripts — can be formulated. To begin with, manuscripts with a public institution can be digitised and made available in the public domain for readers as a searchable document.

However, accessing manuscripts in the possession of individuals is, indeed, a challenge. The website of the National Mission for Manuscripts mentions: “If you have Manuscripts present with you, you may wish to contact the National Mission for Manuscripts… for getting the Manuscripts documented as well as digitized...”

Unfortunately, this strategy places the onus on the owners of the manuscripts. The NMM needs to be positioned as the stakeholder instead. Also, the current offer to document and digitise focuses more on antique value. This does not encourage the owners and may not be useful for readers.

One way to approach this issue is to understand the problem and look for a working model. Here, I will use two concepts in political economy— use-value and exchange-value— as catalysts and distinguish between the manuscript’s content and antique value. Owners of private collections may want to keep the manuscripts for their antique value and not their content value. This is despite problems with their safety and maintenance. Honouring the owners’ sense of possession and addressing their difficulties while devising methods of retrieving the manuscript’s contents for educational value are necessary. Here, I suggest we look at the lockers in banks as a model. The government can get manuscript lockers designed using modern technology with updated facilities at select places in consultation with experts in preserving manuscripts. The manuscript-owners can book a vault and store their collections. This will ensure the protection, preservation,and maintenance of the manuscripts. A legal contract needs to be drafted after discussion with legal experts, bankers, and librarians.It needs to clarify that the manuscripts belong to the owners and the locker providers have no rights over them. To begin with, this will ensure that the manuscripts do not get destroyed due to lack of security or maintenance, while the antique value of the manuscript remains with the owner. In return for these services, the government should request the owners to allow the deposited manuscript to be digitised and placed in the public domain. The ensuing visibility and exposure may even lead to a professional valuation, possibly enhancing the monetary value of some of the manuscripts. This can gradually encourage more people to come forward and use this facility. Unless we explore such novel methods, there is a danger that these ancient manuscripts, especially their content, will be lost to us forever. In many cases, including the Arthashastra, the content of these manuscripts has proved to be of enduring educational value than being merely antiques. The NMM can, therefore, envisage a plan to attract/encourage owners to come forward with their manuscripts.

Putting manuscripts in the public domain can present variety,and plurality, widening our understanding of history, thus bringing greater clarity to the scholarship from the past. A plural and visible history can easily relate to modern scholarship, especially in taking stock of what is accomplished and providing insights in directing future work, echoing the message in T.S. Eliot’s noble lecture, “Tradition and the Individual Talent”.

(A. Raghuramaraju teaches philosophy at the Indian Institute of Technology Tirupati)