The camera was there in London, photographing Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, the suit-clad young lawyer; it followed him to South Africa and, finally, to India, where he became among the most photographed persons of his time. Significant events and movements that he spearheaded, his fasts and public meetings were an integral part of the emerging discourse of an anti-imperialist India. As photographs, reports and discussions of these became available via newspapers, calendar and poster art, they helped iconize the man and his message in the popular imagination. And, yet, at the moment of death, photographers, known as well as unknown, were absent.

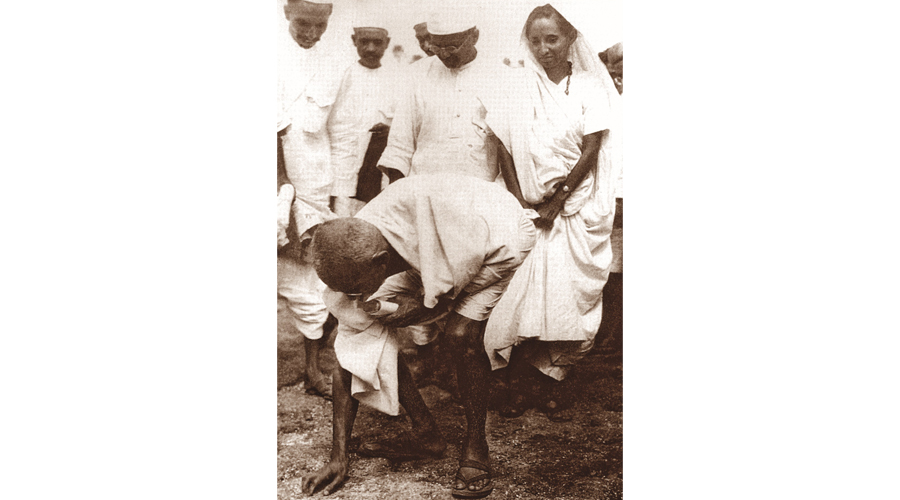

The Dandi salt march of 1930 and its aftermath were among the Mahatma’s most ambitious and physically taxing campaigns. Following the historic ‘Purna Swaraj’ (Total Independence) resolution passed by the Indian National Congress at its Lahore session in December 1929, Gandhi decided that it was time for sustained non-violent action. The salt tax, one of many oppressive economic measures for generation of revenue, gave government monopoly over the sale or production of salt and violations were punishable by law. Thus, on March 12, 1930, with 79 hand-picked followers, all men, Gandhi started on a 24-day campaign of what the art historian, Sumathi Ramaswamy, has evocatively called ‘ambulatory disobedience’. Sarojini Naidu and a few other women joined later — somewhat against the Mahatma’s wishes. On April 6, after days on dusty roads punctuated by measured rest and time for reading and writing, Gandhi lifted a fistful of clayey mud embedded with salt crystals from the sea at Dandi on the Gujarat coast. He was greeted with vociferous cheers — but no camera shutters clicked: that historic morning, for some inexplicable reason, no photographer was present. Thus, the iconic photograph of the Mahatma, with Mithuben Petit behind him, was apparently taken three days later, at Bhimrad, some thirty miles away. Gandhi’s entourage must have realized that as the moment at Dandi remained visually unrecorded, it had to be re-enacted and memorialized carefully by a photographer who remains tantalizingly anonymous. There was nothing serendipitous about the photograph as its composition, timing and who should be in it must surely have been decided by Gandhi and his staff.

The events arising out of the march continued well into the 1930s providing many 'photo-ops’ not only for the Mahatma but also for several others, known and unknown. His name echoed in homes and hamlets and many women and men became short-term heroes, organizing pickets and rallies and picking salt from seashores in all three presidencies. Newspapers were quick to carry reports and photographs, contributing to a much-needed and reliable Dandi archive. By this time, it was clear that the Mahatma and his staff had become fully aware of the power of the image and when, in 1936, his grand-nephew and camera enthusiast, Kanu Gandhi, joined the Sevagram staff, a Rolleiflex was swiftly organized for him. Kanu got to work, photographing the quotidian and the dramatic, the deeply private and the ostentatiously public, such as the one of the Mahatma sitting cross-legged at his desk, caught in mid sentence with Subhas Chandra Bose looking at him intently. A pensive Kasturba looks on. Then there were iconic, though sometimes overused, images of important public meetings, discussions with Jawaharlal Nehru and so on. Kanu’s privileged position allowed him some liberties — he could photograph his grand-uncle shielding himself from the sun with a pillow on his head, working late into the night by the light of a small lamp, waving at crowds from the inside of a railway compartment. Yet, he too had to abide by very clear instructions on how photographs were to be taken — no camera flash bulbs and frontal images only on rare occasions. In 1947, Mahatma Gandhi spent many months in Noakhali, the scene of a series of bloody riots between Hindus and Muslims. Kanu Gandhi recorded him walking through the villages, speaking of the need for peace and harmony. And, as on the instructions of his grand-uncle he had stayed behind in Noakhali, Kanu was not there to take photographs on that fateful January evening — a fact that he must have deeply regretted.

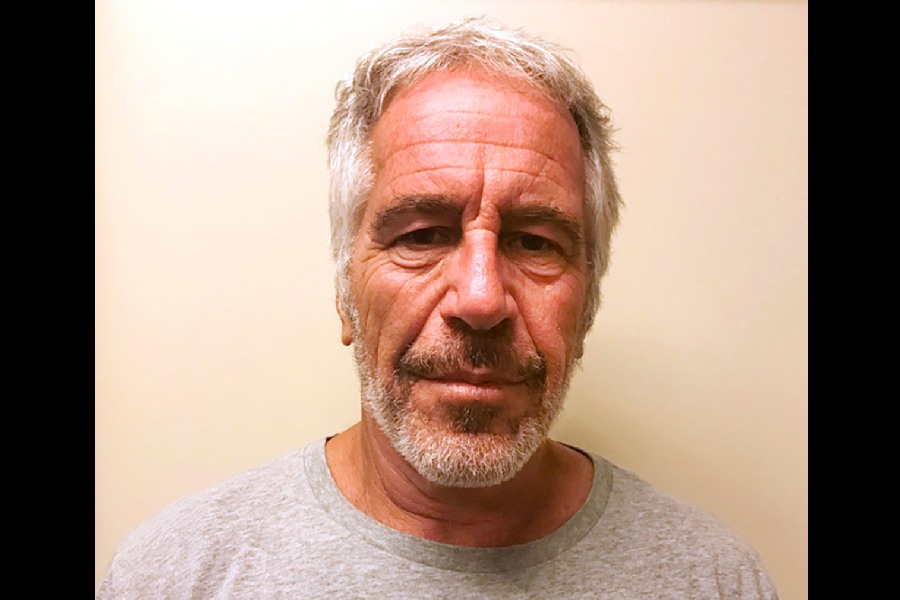

The feeling was shared by Homai Vyarawalla, Margaret Bourke-White, Henri Cartier-Bresson and countless others who had been photographing the Mahatma a few days — if not hours — before. When the three fatal shots rang out, as at Dandi, no camera shutters clicked. The absent camera made way for other artistic imaginings of the assassination, the grieving, and the martyrdom (see Sumathi Ramaswamy’s Gandhi in the Gallery). Yet, photographic absence at the moment of death is more than made up for by Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s lived presence in countless images, some of which were discussed, enabled and choreographed by him.