The farmers’ rally in Delhi, the Kisan Mukti March, organised by the All India Kisan Sangharsh Coordination Committee (AIKSCC) happened the day after the assembly elections in Madhya Pradesh and just before the assembly elections in Rajasthan. The politics of the rally was different from the politics of elections but the two were also intertwined.

The principal agenda of the rally was the demand for a special session of Parliament devoted to farmers’ issues and the passage of two bills drafted by the AIKSCC demanding loan waivers and better agricultural support prices. Unlike the state elections, the rally was conspicuously pan-Indian: the farmers gathered in Delhi had travelled from all over India. Some two hundred organisations had gathered under the AIKSCC’s umbrella. The rally in Delhi was the result of a long drawn-out agrarian crisis that has little to do with the electoral cycle.

It came in the wake of gathering discontent and kisan mobilisation. It was in part inspired by the Long March of peasants from Nashik to Mumbai organised by the All India Kisan Sabha in March where they walked 180 kilometres to draw the attention of the state government to their plight. In Delhi, in September, the Ram Lila ground hosted the Mazdoor Kisan Sangharsh Rally, where Left organisations representing workers, agricultural labourers and peasants gathered to critique the Central government’s indifference to rural livelihoods and the despair gripping India’s villages.

The Long March and the September rally were both initiated by the Communist Party of India (Marxist) and its affiliated workers and peasants organisations. One of the paradoxes of the CPI(M)’s political career is that its presence in class politics remains relatively pan-Indian even as it has shrunk electorally into a provincial rump. After its rout in Bengal and its defeat in Tripura, the bracketed ‘M’ in the party’s name might well come to stand for ‘Malayali’.

This would be cause for regret if only because the CPI(M) is the one party that pays lip service to the idea of a materialist politics. Given the identity politics that defines contemporary India, there is something heroic about tens of thousands of farmers walking for a week led by Left organisations that count for nearly nothing in the electoral politics of Maharashtra, and successfully wringing economic concessions from a BJP state government.

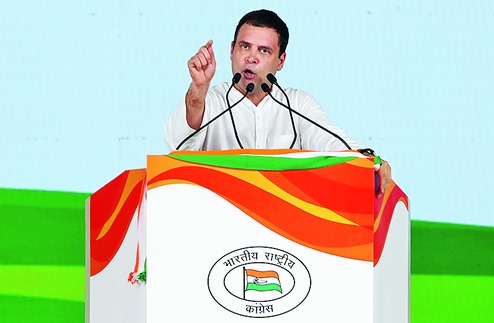

The Left was also important in the organisation of the Kisan Mukti March, which represented the combined efforts of many groups and organisations. Sitaram Yechury addressed the gathering as one of many political leaders. One of the successes of the rally was the number of Opposition leaders who lent it their support. The Aam Aadmi Party as the party of government in Delhi helped with administrative bandobast and the chief minister, Arvind Kejriwal, often seen as the quintessential urban politician, lent it his full-throated support. Rahul Gandhi, despite pressure from the Delhi unit of the Congress to shun Kejriwal, shared a platform with him. They were joined by leaders of the Trinamul Congress, the National Conference, the Nationalist Congress Party (represented by Sharad Pawar himself) and the Communist Party of India. The Bahujan Samaj Party stayed away because it didn’t want to be seen sharing a platform with the Congress till the state elections were over and while the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam didn’t participate, Kanimozhi was careful to send a message saying that her party’s absence was the result of a ‘miscommunication’.

Given that Opposition leaders ideologically and factionally distant from each other chose to make a public show of solidarity on this shared platform, it is reasonable to assume that that they saw political advantage in being associated with this kisan mobilisation. In this election season, many commentators have observed that peasant protests offer Opposition leaders a neutral, non-denominational reason to come together. Being pro-peasant is unifying, not divisive. One of Rahul Gandhi’s most effective political interventions came early in the life of this government when in the wake of the controversy over the land acquisition bill, he slapped a label on the Modi regime which stuck, much to the discomfiture of the prime minister: suit-boot ki sarkar. It forced the government to abandon the bill: a rare but significant Opposition victory.

Why, then, are mainstream political parties like the Congress content to ride on the coattails of political mobilisations led by an electorally insignificant Left? It’s encouraging to see Rahul Gandhi and Sharad Pawar sink their differences to lend fraternal support to the farmers movement and critics of the Modi government will hope that this solidarity translates into an electoral dividend, but it does raise a question: why haven’t they been prime movers in this mobilisation? If the peasant cause is a unifying cause, if it is born out of an agrarian crisis that has made a significant part of India’s electorate despair, if the Opposition is looking for a way of outflanking the Bharatiya Janata Party’s populist melding of vikas and Hindutva, why would the Congress or the NCP not be fighting to be seen as the vanguard of a non-sectarian populism of the sort represented by the Long March earlier this year?

This is not a rhetorical question, nor is it a preliminary to Congress-bashing. It’s born of puzzlement that a party that pioneered NREGA, that has a history of populist policymaking, would choose to be a follower rather than a leader in this space. One answer to the question has been that the CPI(M) has always had pockets of support in states like Andhra Pradesh, Bihar and Maharashtra outside its traditional strongholds, and that events like the Long March represent the total mobilisation of a small political base. The suggestion here is that the symbolic success of the march is no guide to its electoral significance. This may well be true, but it doesn’t explain why Sharad Pawar’s party or the Congress in Maharashtra didn’t mobilise their much larger rural constituencies to make the political weather in an election season in which these parties are fighting for their lives.

An interesting but circular answer is that the CPI(M) is a cadre-based party made for grass-roots mobilisation while most other Opposition parties aren’t. Parties of government like the Congress become used to using the sinews of the State and prolonged spells out of power rob them of the resources and the networks of patronage and clientage necessary for winning elections. Perhaps it is unfair to expect the Grand Old Party to revisit its historically agitational roots where Gandhi and his lieutenants used peasant militancy and kisan sabha movements for large political ends.

Or perhaps there is a more grounded answer to this question, one that politicians understand in a way that naïve commentators don’t: that people might rally as peasants but they vote as members of communities defined by caste, clan and religion. If accurate, this would be a bleak and depressing truth. The only way it can be tested is for a major party like the Congress to commit itself to non-denominational populist mobilisation as an alternative to an identity-based balancing act.

Given the BJP’s success in peddling majoritarianism, it’s understandable that the Congress is concerned about not seeming ‘anti-Hindu’. Given the near-existential threat that the electoral triumph of Hindutva poses to the Republic, it isn’t hard to empathise with the impatience of those who see the charge of ‘soft Hindutva’ levelled at the Congress as badly-timed carping. But since the challenge of Hindutva is here to stay regardless of the outcome of the 2019 election, it’s reasonable to ask that Opposition parties commit themselves in the medium term to creating an inclusive mass constituency as a counterpoise to the BJP’s success in creating a divisive one. The republican inheritors of Gandhi can’t put their faith in a Namierite politics of faction and sect, of patrons and clients. A subcontinental nation, as the BJP has malignly demonstrated, can’t be won with the politics of the borough or the mofussil: it has to be inspired by large causes that travel well.

mukulkesavan@hotmail.com