There's a lot of news going on about the 'black hole girl' right now, and how she's being given too much credit for her role in the historic first image of a black hole. Because this is too important, I want to set the record straight.

Once `Katie Bouman` became the 'face' of the black hole photo, and articles began to call her 'the woman behind the black hole photo', an assortment of people that I'm strongly inclined to call incels but won't, decided to figure out just how much of a role she had in it. Why? You'd have to ask them. Something about her attractiveness, youthfulness, and femaleness disturbed them to the point where they had to go digging.

And after digging, they found Andrew Chael, who wrote an algorithm, and put his algorithm online. Andrew Chael worked on the black hole photo as well. And because people kept saying that Katie Bouman wrote 'the algorithm', these people decided that 'the algorithm' in question must be Chael's.

So they looked at Chael's GitHub (software development platform) repository and checked the history. The history showed that Andrew Chael made 850,000 commits to the GitHub repository, while Katie Bouman made only 2,400.

'Oh my god!' they all said. 'He did almost all of the work on the algorithm and yet she's the one getting all of the credit!'

They dug a little deeper - but not much - and discovered that the algorithm that 'ultimately' generated the world-famous photo was created a different man, named Mareki Honma.

'She's taken the credit from two men!' they gasped. 'Feminism and the politically correct media are destroying everything!'

The author is a programmer and data analyst with a love for physics. She originally published the above article as a `Facebook note`. Republished here with permission.

There were, of course, those who tried to be kind. 'She's always said that this was a team effort,' they said. 'We don't blame her, we blame the media. She didn't ask to become the poster girl of a team project she barely contributed to.'

Meanwhile, Andrew Chael - a gay man - tweeted in defense of her. He thanked people for congratulating him on the work he'd spent years on but clarified that if they were doing so as a part of a sexist attack on Katie Bouman, they should go away and reconsider their lives. He said that his work couldn't have happened without Katie.

And it turns out that he was the one who took the viral photo of Bouman, specifically because he didn't want her contributions to be lost to history.

So I decided to find out for myself what Katie Bouman's actual contributions were. As a programmer, I'm well aware that the number of GitHub commits means nothing without context. And Chael himself clarified that the lines being counted in the commits were from automatic commits of large data files. The actual software was made up of 68,000 lines, and though he didn't count how many he did personally, someone else assessed that he wrote about 24,000 of those.

Whether 68,000 or 24,000 -- it's more than 2,400 right? Why call it 'her' algorithm, then?

Because there's more than one algorithm being referenced here. These people just don't realize it.

I'll work my way backward because it's easier to explain that way.

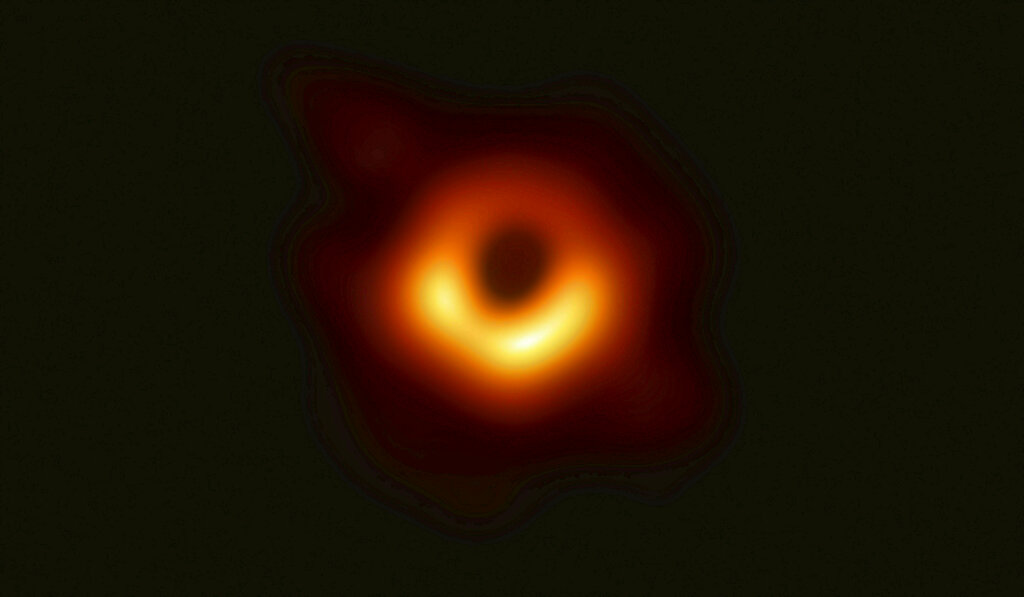

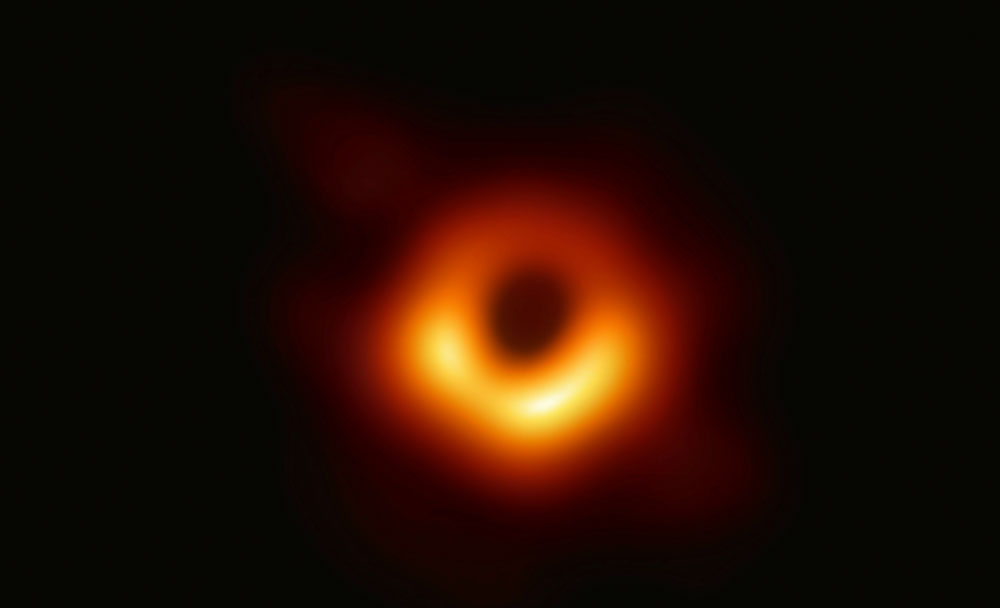

The photo that everyone is looking at, the world famous black hole photo? It's actually a composite photo. It was generated by an algorithm credited to Mareki Honma. Honma's algorithm, based on MRI technology, is used to 'stitch together' photos and fill in the missing pixels by analyzing the surrounding pixels.

But where did the photos come from that are composited into this photo?

The photos making up the composite were generated by four separate teams, led by Katie Bouman and Andrew Chael, Kazu Akiyama and Sara Issaoun, Shoko Koyama, Jose L. Gomez, and Michael Johnson. Each team was given a copy of the black hole data and isolated from each other. Between the four of them, they used two techniques - an older, traditional one called CLEAN, and a newer one called RML - to generate an image.

The purpose of this division and isolation of teams was deliberately done to test the accuracy of the black hole data they were all using. If four isolated teams using different algorithms all got similar results, that would indicate that the data itself was accurate.

And lo, that's exactly what happened. The data wasn't just good, it's the most accurate of its kind. Five petabytes (millions of billions of bytes) worth of accurate black hole data.

But where did the data come from?

Eight radio telescopes around the world trained their attention on the night sky in the direction of this black hole. The black hole is some ungodly distance away, a relative speck amidst billions of celestial bodies. And what the telescopes caught was not only the data of the black hole but the data of everything else as well.

Data that would need to be sorted.

Clearly, it's not the sort of thing you can sort by hand. To separate the wheat (one specific black hole's data) from the chaff (literally everything else around and between here and there) required an algorithm that could identify and single it out, calculations that were crunched across 800 CPUs on a 40Gbit/s network. And given that the resulting black hole-specific data was five petabytes (hundreds of pounds worth of hard drives!) you can imagine that the original data set was many times larger.

The algorithm that accomplished this feat was called CHIRP, short for 'Continuous High-resolution Image Reconstruction using Patch priors'.

CHIRP was created by Katie Bouman.

At the age of 23, she knew nothing about black holes. Her field is computer science and artificial intelligence, topics she'd been involved in since high school. She had a theory about the shadows of black holes, and her algorithm was designed to find those shadows. Katie Bouman used a variety of what the Massachusetts Institute of Technology called 'clever algebraic solutions' to overcome the obstacles involved in creating the CHIRP algorithm. And though she had a team working to help her, her name comes first on the peer-reviewed documentation.

It's called the CHIRP algorithm because that's what she named it. It's the only reason these images could be created, and it's responsible for creating some of the images that were incorporated into the final image. It's the algorithm that made the effort of collecting all that data worth it. Any data analyst can tell you that you can't analyze or visualize data until it's been prepared first. Cleaned up. Narrowed down to the important information.

That's what Katie Bouman did, and after working as a data analyst for two years with a focus on this exact thing - data transformation - I can tell you it's not easy. It's not easy on the small data sets I worked with, where I could wind up spending a week looking for the patterns in a 68K Excel spreadsheet containing only one month's worth of programming for a single TV station!

Katie Bouman's 2,400-line contribution to Andrew Chael's work is on top of all of her other work. She spent five years developing and refining the CHIRP algorithm before leading four teams in testing the data created. The data collection phase of this took 10 days in April 2017, when the eight telescopes simultaneously trained their gazes towards the black hole.

This photo was ultimately created as a way to test Katie Bouman's algorithm for accuracy. MIT says that it's frequently more accurate than similar predecessors. And it is the algorithm that gave us our first direct image of a black hole.

Around the internet, there are people who have the misperception that Katie Bouman is just the pretty face, a minor contributor to a project where men like Andrew Chael and Mareki Honma deserve the credit. There are people pushing memes and narratives that she's only being given such acclaim because of feminism. And because Katie Bouman refuses to say that this was anything other than a team effort, even the most flattering comments about her still place her contributions to the photo at less-than-equal contribution to others.

But I'm writing to set the story straight:

When it is written that Katie Bouman is the woman 'behind the black hole photo', it is objectively true. She wasn't the only woman, but her work was crucial to making all of this happen.

When Andrew Chael says that his software could not have worked without her, he isn't just being a stand-up guy, he's being literal. And there are those who could just as easily say the same about his contribution, or the contributions of many others.

And while it's true that every one of the 200+ people involved played an important role, Katie Bouman deserves every ounce of superstardom she receives.

If there must be a face to this project - and there usually is - then why shouldn't it be her, her fingers twined across her lips, her gleeful eyes luminous and wide with awe and joy?

Edited:

Thinking on it a little further, I felt I should clarify that I'm not actually trying to downplay Andrew Chael. His imaging algorithm is actually the result of years of effort, a labor of love. Each image that could be composited into the final photo brought with it a unique take on the data, without which the final photo wouldn't have been complete.

So let's take a moment to celebrate the fact that two of the most integral contributors to the first direct photo of a black hole were

a woman

and a gay man.