Operation Sindoor with its evocative Hindu name may have avenged Pahalgam to some extent. But will it end terrorism even if all the people killed — and we won’t know how many they were until India and Pakistan synchronise lists — were terrorists? Will it solve the Kashmir dispute, which lies at the heart of the subcontinental divide irrespective of the Hindu-Muslim differences that Pakistan’s army chief, General Asim Munir, trotted out recently?

Kashmir could, in fact, be the crux of the problem. Mirwaiz Umar Farooq, the chairman of the All Parties Hurriyat Conference, a man with an important religious and political role in the Kashmir Valley, claimed during a visit to Calcutta (and reiterated in Srinagar) that Kashmir is part of “the unfinished business of Partition”. Could Pahalgam not have been the mischief of Kashmiris who gloated over the expulsion of the Pandits and resented it when Articles 370 and 35A were repealed and the already truncated Jammu and Kashmir state reduced to two Union territories? Omar Abdullah’s admission in the legislative assembly that his government had issued more than 35.12 lakh domicile certificates in two years, 83,742 of them to individuals who were not originally state subjects, must rankle with constituents.

Meanwhile, the deadly tit-for-tat game so exultingly pursued by both sides justifies Lieutenant-General Vijay Oberoi’s dismissal of our TV studios as “pits of stupidity”. It seemed an indulgent description as a leading anchor asked each of his panellists to swear hand on heart that no outside power (presumably the United States of America) would interfere when India wreaked vengeance on Pakistan for the massacre.

How could any anchor be so certain immediately after the butchery that Pakistan alone must bear the full blame? How could he have known that India’s retaliation would be military? Or that the New Delhi worthies on his panel could determine how international powers respond? The 'theatery' — to use a Bengali colloquialism which has no exact English equivalent — that has aggravated every move since that fateful April 22 suggested that the make-believe world of television had taken over from real life as India and Pakistan jubilantly hurtle towards disaster. The care each side takes to keep the other informed of its version, the calibrated menace of politicians’ pronouncements and the blood-curdling media threats seem to have been designed to haunt even the ungotten and unborn with the horrors of Armageddon.

Something about these theatrics, including 'false flag' allegations to deceive people into thinking they were carried out by someone else, strikes one as even more phoney than the so-called 'Phoney War' before Germany invaded France in May 1940. I was a toddler then but remember the forest of silver barrage balloons surrounding Howrah Bridge like giant fish swimming in the air before we were packed off to the safety of what was then Benares Cant. The peril for me wasn’t from Japanese bombing but boisterous American soldiers who enjoyed gladiatorial contests between unwary little boys on whom they forced boxing gloves. Black soldiers, the first I had set eyes on, were different as they dispensed chewing gum, again, the first I had seen, at their Dhakuria Lakes barracks.

Roll on the two wars of 1962 and 1965. I thought Jawaharlal Nehru’s "my heart goes out to the people of Assam" speech after Bomdila fell very moving and was surprised to learn it had been ill-received. I also misunderstood Doordarshan’s commission to produce a radio feature on Calcutta’s Chinatown. I spent a lot of time and effort on the project and was quite pleased with the result until an Akashvani boss telephoned from Delhi to denounce my feature for stressing Tangra’s links with Taiwan instead of eulogising India for having always befriended the communists of mainland China. The 1965 war remains in my mind as a jingle that my long-deceased friend, Manabendra Narayan Deb, an Assamese princeling who worked for the Hindustan Standard and later became the Financial Times night editor in London, picked up from Pakistan radio. “Cholo Mujahid bhai, Amra kaffir dhortey jai!” he would burst out without warning.

Would India ever be the setting for a war I wondered, and my mother replied “Only if there’s a civil war.” That almost happened in 1971 when The Observer in London, the world’s oldest Sunday newspaper, published my report under the eight-column headline, “Flight Of The Hindu Millions”. The Bangladesh war was part of our own history. All the Operation Searchlight victims in our refugee camps were Hindus. If ever "every Indian's blood (was) boiling”, as Narendra Modi said in his first Mann Ki Baat broadcast after Pahalgam, it was then.

But India displayed little of the hysteria that convulsed even phlegmatic Britain in moments of crisis. Official action still can’t be mistaken for spontaneous outbursts of public feeling. When Rajnath Singh assured the Sanatan Sanskriti Jagran Mahotsav that the “nation will get what it wants under PM Modi”, he meant that the National Democratic Alliance government would deliver what it thought the people wanted. The bulldozing of allegedly unauthorised Muslim houses, abolition of Islamic names like Allahabad or the targeting of individual Muslims are the handiwork of government departments that take their cue from the party in power. Strangely, the current crisis seems to have produced little of the genuine outrage that inspired British objections to green pillar boxes because green was the colour of Irish rebels. Also to red ones after the Daily Mail published a forged letter purportedly written by the Comintern chief ordering British communists to engage in seditious activities.

Ultra-patriotic Brits forced Lord Mountbatten’s father, Prince Louis of Battenberg, to resign as First Sea Lord. King George V himself felt obliged to change his name from Saxe-Coburg-Gotha to Windsor, famously provoking his first cousin, Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm II, to mock that he was going to the theatre to see a performance of “The Merry Wives of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha”. As Graham Greene recorded in his autobiography, "A German master was denounced to my father as a spy because he had been seen under the railway bridge without a hat, a dachshund was stoned in the High Street, and once my uncle Eppy was summoned at night to the police station and asked to lend his motor car to help block the Great North Road down which a German armoured car was said to be advancing towards London."

Similar mysteries baffle us too. People ask why there were no security personnel or closed-circuit TV cameras in and around the Baisaran Valley where the murders took place. They wonder why the shadowy The Resistance Front, which initially claimed responsibility for the killings, as it had done for earlier attacks in Kashmir, retracted the admission four days later although the stated reason for TRF's ire — Delhi’s policy of allowing all Indian citizens to work in Kashmir which Article 35A did not — hadn’t disappeared. Why were local nationalists not suspected?

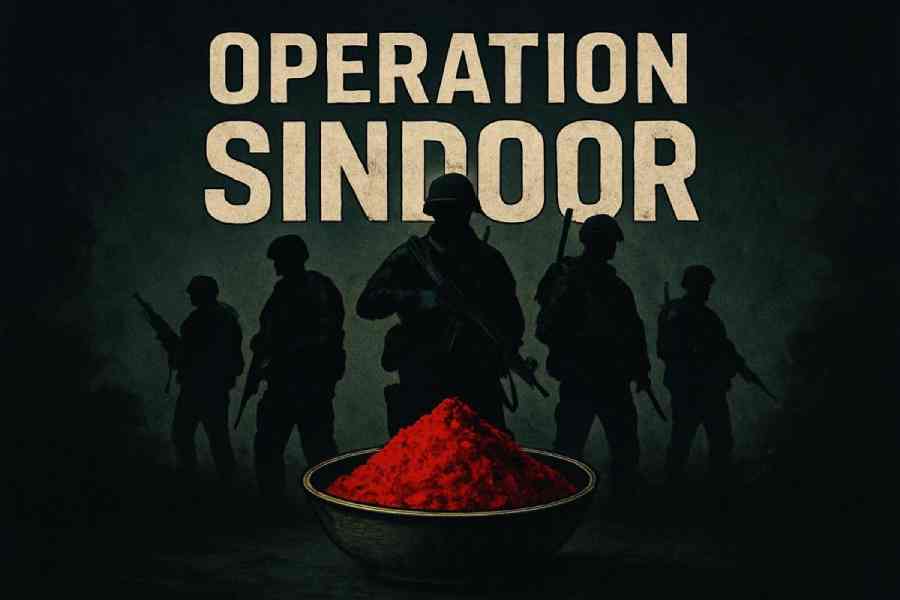

By calling the retaliation Operation Sindoor, India may have reinforced General Munir’s view of a cultural-communal divide. If the Pahalgam killers abused the Kalima to butcher Hindu men, sindoor, the exclusive auspicious symbol for married Hindu women, is also abused during communal riots. Kashmir is a territorial and not a communal problem. Too much bitterness lies between India and Pakistan for relations to be hunky-dory if the dispute is resolved but normalcy will remain elusive if it is not. This is the bleak message of the present tragic sequence.

At least, the daily Beating Retreat pantomime by India’s Border Security Force and the Pakistan Rangers at the Attari-Wagah checkpost has been stopped. What may have started as an innocent display of machismo had degenerated into war by other means. That might have been amusing if real war on account of the festering Kashmir dispute did not loom so near.