It is 173 years since the publication of the first critical edition of the Rig Veda Sanhita, an immense scholarly accomplishment, more so because in presenting the only known complete commentary by Sāyaṇācārya, it remains one of the few Western Vedic studies to engage seriously with the indigenous interpretive tradition.

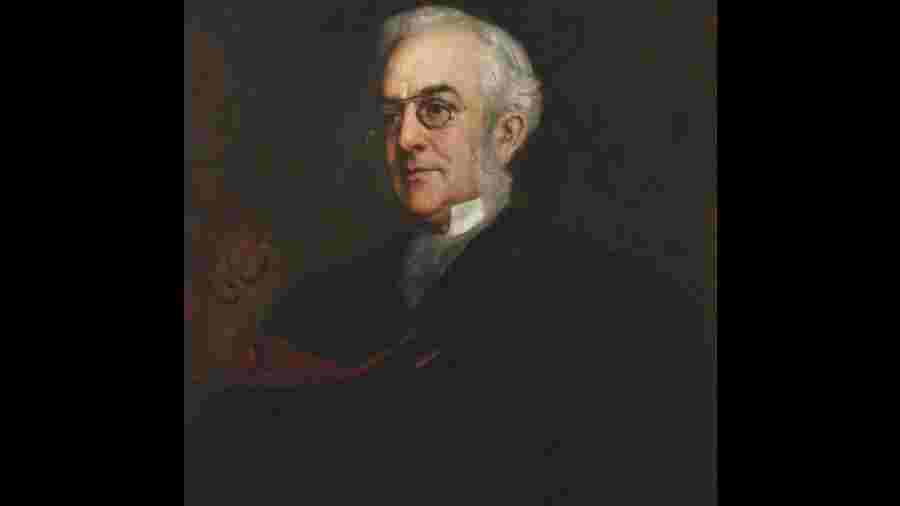

For Max Müller, the editor, publishing it had proved difficult: only through the funding of the Court of Directors of the East India Company could the work see the light of day. In contrast to the Company’s objective, which was to understand its colonial subjects better, Müller’s was to give Indians access to their own heritage and identity.

On the one hand, his comparative method was certainly driven by empathy for ancient India—though this feeling did not extend to a support for Indian decolonisation. On the other, Müller’s idea that Hindu mythology, indeed mythology in general, epitomised a process of decay, an obfuscation of a primordial monotheistic religion centred on the Sun, which had arisen through his study of language in the Ṛgveda, seems less motivated by fellow feeling and more so, one may venture to suggest, by his Christianity.

Müller’s study of Ṛg Vedic Sanskrit, especially his ideas on personification in that work, had led him to the important linguistic conclusion that all language was figurative. Ancient humans attribute linguistic gender and other personifying elements to make abstract concepts and natural phenomena concrete, a tendency evinced in the hymns of the Ṛgveda, one of the earliest examples of human literature in which the gods primarily personify natural events and elements, such as thunder, dawn, fire and rain. Müller argued that over time the original meanings of words were forgotten so that greater mythologising eventually led to concepts that had deviated from their original intentions. Beginning with the addition of gender to nouns, the creation of more elaborate narratives of personification epitomised to him a long-term process of language degeneration.

From this position, Müller made a deeply problematic second step in his reasoning. If all language is eventually falsifying, then Hindu mythologies are useless, indeed ‘ridiculous’, and Hindu polytheism itself, playing out in a panoply of myths, was a corruption of the original monotheistic religion, which ancient Hindus were trying to put to words. Müller reduced the various ways myths can be appreciated to a single interpretation. On the one hand, he acknowledges the poetic capacity of language, while on the other, he betrays a suspicion of the poetic mind, of non-monotheistic religions, and, indeed, appears to believe—puritanically-- that all mythology is depravity.

In fact, this monotheistic bias runs through his assessment of Raja Ram Mohun Roy, the 19th century Bengali reformer, in whose rejection of Hindu polytheism and championing of the philosophy of Upaniṣads as the one true monotheistic message of all Hinduisms, Müller saw a reformer against idolatry.

Müller’s vision of a primeval, ‘true’ Hinduism and his related theory of a common, sun-worshipping Aryan identity for the British and Indians, for which he was mocked in a contemporary article (Richard Frederick Littledale’s “The Oxford Solar Myth” in Kottabos, 1870), had problematic consequences, leading to early far Right ideologies of an Aryan brotherhood in Germany.

Nevertheless, it is important to emphasise that his understanding of India was imbued by a marked difference of attitude to the dominant intellectual attitude of the times, which was to regard anything non-European as inferior. In his essay, “Science of Religions”, he writes: “All higher knowledge is gained by comparison, and rests on comparison.” Undertaking comparison required an open-minded attitude, articulated by the German philosopher, Johann Gottfried Herder, some years before Müller. In his “This Too a Philosophy of History for the Formation of Humanity” (1774), Herder speaks about empathy – Einfühlung - as a historical ability “to transport to oneself into the age… into the entire history, feel your way into everything”. Such an attitude required a historian neither to be too close to the subject matter to self-identify, nor to be too distant so as to be hostile and prejudiced.

Müller’s own spirit of scholarship demonstrates a similar attitude of Herderean einfühlung. In his essay, “Comparative Mythology”, he writes: “[The] more intensely we read, the more our thoughts are engaged and our feelings warmed, and the history of those ancient men becomes, as it were, our own history,-- their sufferings our sufferings—their joys our joys. Without this sympathy, history is a dead letter, and might as well be burnt and forgotten.”

There were limits to Müller’s einfühlung, for example expressed in his Protestant horror at “how the Sacred Books of the East should, by the side of so much that is fresh, natural, simple, beautiful and true, contain so much that is not only unmeaning, artificial, and silly, but even hideous and repellant.” (Preface to Sacred Books of the East). While an exceptional comparative linguist, his cultural, historical and religious arguments, grounded only on language without further areas of evidence, are open to questions.

For Müller, the paradigmatic example of human unity is captured in the dialogue between Uddālaka Āruṇī and Śvetaketu in the Chāndogya Upaniṣad Book 6, which occupies a significant section of his preface to the first volume of the Sacred Books of the East, and appears to me to capture his core ideological vision. In the famous episode, the father explains to his son how a single essential entity, Sat, separates itself into three elemental constituents, fire, water and earth, and through subsequent combinations with each of those constituent elements, it produced all known phenomena and names. At death, each of these elements return sequentially to the former, ending again in Sat. Hence in knowing that the underlying basis of all phenomena is formed by these three, one would know the underlying basis to existence itself. The father further instantiates it with the crumbled seed of a banyan tree, to argue that in each minute part of the broken seed, the larger banyan is contained. Müller’s concern in using this passage is to sympathise with the Upaniṣadic inquiry into the subtle essence of existence, and it seems to me that his studies in Sanskrit and Indian religions and, indeed, the entire enterprise of the Sacred Books of the East are, to a significant degree, connected to a personal search for the subtle essence in all humankind. The need to transcend individual dichotomies of religion and language in his studies was, in fact, a deep spiritual need to understand an all-pervasive human reality, which could not be limited to names and definitions.

Müller’s broad view of religions was to leave a profound mark on Victorian intellectuals, such as the novelist, George Eliot, whose own comparative view of religions, as instantiated in the sympathetic vision of Daniel Deronda, parallels Müller’s writings on Sanskrit. Elliot’s Notebooks to Middlemarch contain more than 30 pages of entries on various aspects of Sanskrit literature and Indian religions and philosophies gleaned from Müller’s History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature and Lectures on the Science of Language. The accuracy and thoroughness of her notes show that she had engaged closely with Müller’s writings.

In Müller’s attitude to mythology, to India itself, lay an ambivalence: he exults in the imaginative richness of Indian myth and polytheism at times rhapsodically; on the other, as a Victorian rationalist and German Protestant, he finds them distasteful, their interpretive wildness in need of taming. His comparative mythology and idea of religions were based on an expansive knowledge basis. Yet behind all his deep respect for early Indian intellectual traditions, lay a man who believed that India was better a servant of the British. While his scholarship was impeccable, from which we continue to learn, there are hidden agendas at play - theological, patriarchal, preoccupied with race - of which we would do well to be mindful.

(Bihani Sarkar is Departmental Lecturer in Sanskrit at the Faculty of Oriental Studies, University of Oxford)