Nearly every person in Odisha and many beyond are devoted to Lord Jagannath and are concerned about what's happening to the temple complex in Puri.

Unfortunately every person or commodity has a life span, including the Earth itself. Therefore the temple complex is not immortal and has a limited life.

By constantly focusing our attention on this complex and continuously addressing the minor and major problems in the structure, the life of the temple complex can be extended, so as to seem that it will stay intact even in the distant future.

Setting it right

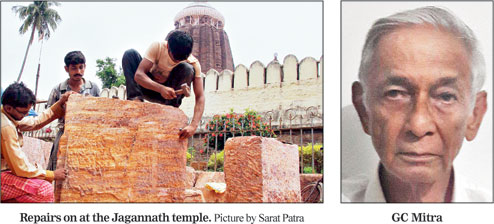

In the 1970s, the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) took over charge for maintenance of the temple complex. Since then, about 17 stones have reportedly fallen from the main temple and other places. In 1992, corbel stones fell in front of the idol of Lord Balabhadra, which triggered an alarm all over the country. The then chief minister Biju babu had a responsive nature and called a meeting in September 1992 at the Townhall in Puri. The people attending this meeting spilled into the corridors of the hall. I had the privilege of being present. It was astonishing to see that the chief minister was profusely perspiring, but still answered patiently all the questions asked. This is where we learned about the ASI and some technical details about the temple complex, its problems and possible solutions.

After that, the works department got involved in this work and a letter was addressed to the Government of India expressing concerns of the Government of Odisha in particular and the people of Odisha in general on November 8, 1992. Action was immediately taken in the last week of November. The deities were shifted to the front temple - Jagmohan - where the Lords sat on a neem pedestal singhasan (altar) (18ftx12ftx2ft) cladded with a brass sheet, prepared by the handicrafts department of Odisha.

In February that year, it was suggested by the Government of India that the Government of Odisha should take over the structural conservation works of the main Garvgriha (sanctum sanctorum). That's when the government engineers started to learn about archaeological conservation. The director (conservation) Grover, director (science) R.K. Sharma, S. Maity, Chowle, all from ASI and A.P. Gupta from IIT, Kharagpur, were the guides.

Garvgriha repairs

This is a Rekha type temple. The sculptors of Odisha conceived this type of temple about 1,800 years ago. Temple building, evidence suggests, began about 1,500 years ago, starting with the smaller temples. Higher and higher temples were built subsequently, the effort culminating with the Sun Temple at Konark, which stood at a height of about 213ft (estimated - now collapsed). The inside rooms of all Odissan temples were square in plan. The thickness of four walls around this space was about 50 per cent of inside of clear dimension. The height of the temple could be four times the room size, but the limit was five times. (The failure of Konark main temple was possibly because the height was far more than five times the room size - 5 x 38ft - 190ft. There were multiple floors when the temple height was tall. For example, the Puri temple has three storeys. These diaphragms assist the temple to increase its resistance against earthquakes and wind pressure.

In the case of the Puri temples, the floor heights are 13.8m(45.3ft), 10.7m (35ft) and 9.82m (32ft). The total height of the temple from the bottom of Nilachakra is 53.6m or about 173ft. The thickness of the floors is about one metre in which there are slits, which serve for ventilation. The temple is constructed of a less dense variety of stone, Khondalite, for ease of work, engraving statues, panels, moulds and so on. These stones have nevertheless withstood the vagaries of Puri's saline atmosphere comprising sulphate, chloride, nitrates and other dissolved solids for 800 years. No mortars, neither lime nor cementing materials, were used in these temples and the stability of the temple depended totally on anchorage between stones and provision of iron dowels. Iron dowels have a story. They have rusted over the past 800 years and are generating forces between stones. As a result, fascia stones are falling off. This happened when two amla stone segments fell in the late 1990s. The ASI replaced them.

Works done

The corbel stones, which support the floor stones, were in distress as the spans had to be reduced from 8.38m (30ft) to about 3m (10ft). The stress was at the edge of the protruding corbel stones and due to rusting of steel anchorages over 800 years, the cantilever corbles were pushed from the inside and falling off. Therefore a stainless steel space frame had to be introduced at a high level to support the floor slab. From this space frame each individual corbel stone found its stability.

The worn-out stones in the walls were replaced on the inside and outside surfaces of the temple (this was not necessary for the floors, which were good condition). The entire inside, on the ground and first floors, the joints between stones were sealed and grouted. The first floor work could be done by using scaffolding and stone steps available from higher levels onwards, concealed in the walls. However, to allow movement of moisture, trapped inside the stone joints, grouting on the outside was done in bands to achieve moisture movement.

There is no access to the second floor. Only four (13inchx18inch tunnels) were available at the clerestorey level at nearly the top of the temple. A large number of stones had fallen from the walls and the roof had fallen off. Nothing had been done before 1992, except giving a cushion of one metre thick rice husk, to minimise the shock and noise from the falling stones.

In 1992-93, the rice husk was taken out from the inside, some of the fallen stones were reset, joints sealed and grouted with polymer cement suspension.

Quite a few external and internal stones and statues needed to be fixed to the walls by drilling holes through them and thereafter inserting 25mm dia, stainless steel threaded bars, after which PMC or Epoxy grouting was done. On the top floor (second), no pinning could be done due to reasons of accessibility of the machine.

Conservation

In the past 65 years, we have seen how Khondalite stone statues in the Rajarani, Konark and other temples have deteriorated. Rajarani statues were the best exhibits from Odisha, but their pristine sharp features are already gone. The fate of statues and engravings of Konark, Sri Lingaraj (sandstone), Shri Jagannath and other temples is far worse.

Khondalite is a metamorphie-sedimentary rock, banded structure, brownish in colour with quartz, graphite and other minerals. Its porosity varies from 7.8 per cent to 12.4 per cent. For this reason, it is susceptible to weathering, which results in concerting the material of either Kaolin with quartz and ferric hydroxide or in more advanced stages, a laterite material containing mainly hydroxides of iron and aluminium.

For stone conservation, a vast number of materials are used depending on their composition. For Khondalite strengtheners, a base of ethyle silicate are being used and on penetrating the stone it is converted back into silica or quartz and becomes a mineral binder, silica gel, which combines with stone. It allows the stone to "breathe", thereby eliminating moisture (water vapour) pressure on the stones.

However, Khondalite being a comparatively weak material, the disintegration due to pollution and water action still occurs. Therefore loss of beauty of the statues and engravings cannot be altogether prevented and with time all these temples, including Konark, will only be plain masses of rock.

In conclusion, material science is developing and with effort, we may be able to substantially prolong the life of the temples, but we will not be able to preserve their original beauty.

• The writer, an engineer and expert on temple conservation, is associated with the Jagannath temple repairs