Our story begins nearly 600 years ago in Portugal. In 1455, the reigning monarch, Afonso V, was blessed with a son and heir. Growing up, the prince was unpopular among his peers. He appeared to despise court intrigues – a way of life for European monarchies of the day and seemed impervious to any kind of external temptation and influence. The power brokers of the empire were worried of the day he was made the overlord.

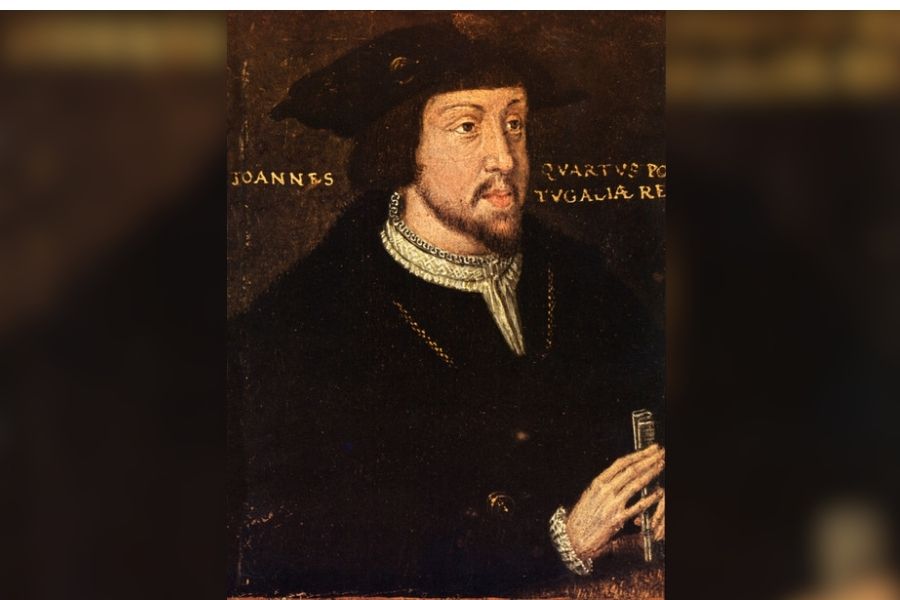

In 1477, King Afonso V chose to retire to a monastery to spend his last years embracing religion. The prince was now anointed as John II, the new monarch. But the old patriarch still yielded considerable influence, even though he was removed from public life. It was only in 1481, when his father passed away that John II ‘came to power’ for all practical purposes. Growing up, John II had been less than impressed by the powers exercised by the nobility. His sworn aim was to cut the landed aristocrats back to size. However, it was the nobility and their lands that financed the kingdom’s coffers to a large extent. John II’s ruthless crackdown on the noblemen of the kingdom meant the finances suffered. The king had to find a way out. He chose to turn to history.

John II’s great uncle, Henry the Navigator, was a pioneer in European maritime explorations in the early years of the 15th century. But after Henry’s death in 1460, the maritime explorations gradually winded to a close. It was on this that John II focused his attention. With active royal encouragement, Portuguese adventurers once again sailed their ships to distant lands. The main focus was to sail south, down the west coast of Africa and thence forward, try and discover the route to India and gain entry into the famous and lucrative spice trade.

King John II of Portugal Wikimedia Commons

John II anointed two well-known diplomats, Pêro da Covilhã and Afonso de Paiva, to undertake a mission to the near East and adjoining regions of Asia and Africa. On May 7, 1487, de Paiva and da Covilhã set out from Santarém on their momentous voyage. Together, the two men travelled through Barcelona, Naples, Rhodes Island (Greece), Alexandria, Cairo, Suakin and finally, Aden. From here, de Paiva left for Ethiopia and da Covilhã began his journey for India by sea. He arrived first at Cannanore and then Calicut in modern-day Kerala, and then onwards to Goa. It is estimated that in was 1489 when he first arrived at the Malabar Coast. From Goa, he started his journey back to Cairo via Hormuz.

At Cairo, da Covilhã met two messengers from his king, Rabbi Abraham and José Sapateiro of Lamego. Through José, he sent back his letters and notes to King John II. These contained accounts of his journey, his observations on the cinnamon, black pepper and clove trade in Calicut, and most importantly, his recommendation for a maritime trip to India. Da Covilhã strongly suggested that any future attempts should sail along the west coast of Africa, turning the Cape and reaching Madagascar, which was to be used as the base for the remaining part of the journey to Malabar.

A bust of Pêro da Covilhã Wikimedia Commons

Sadly for him, da Covilhã would never return to his beloved homeland, spending the rest of his life as a state guest in the Kingdom of Prester John (modern Ethiopia). But the notes and letters he sent back would form the foundation for the first serious attempt at trade from Europe with India – led by Vasco da Gama in 1497.

Vasco da Gama’s first trip was logistically quite disappointing – he failed to secure any privilege from the Zamorin (the Hindu ruler) of Calicut, lost two ships and over half of his men on the return journey and only brought back a limited amount of spices. Yet, back home, he was celebrated as the pioneer for opening a direct sea route to India. It paved the way for subsequent armadas to sail to India and bring back not only spices, but also muslin cloth, which were soon to be in great demand across Europe, and would go on to fulfill the now departed King John II’s dream of filling up the Portuguese royal treasury.

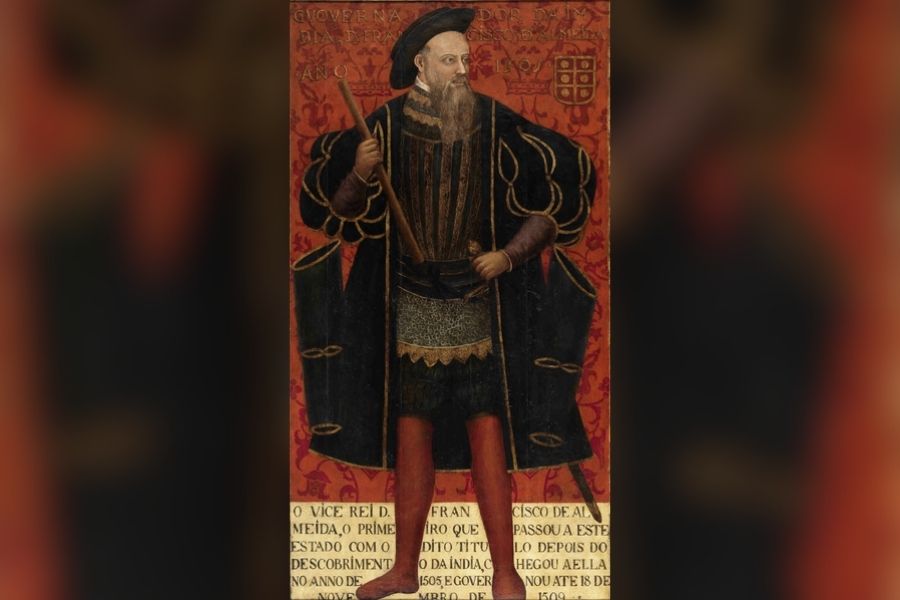

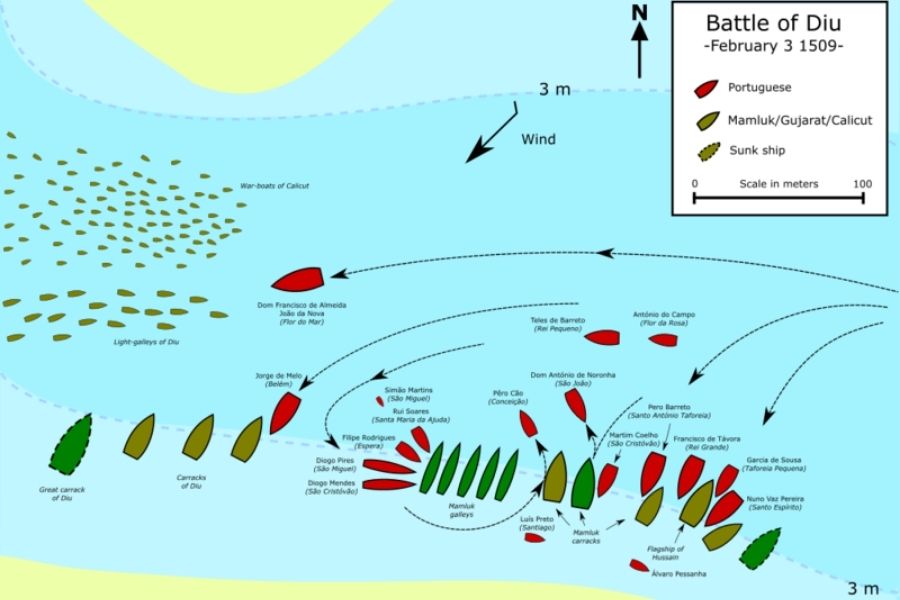

On 25 March, 1505, Francesco de Almeida was appointed the first Viceroy of Estado da Índia (Portuguese State of India) and established his capital at Cochin on the Malabar Coast (present-day Kochi). In 1509, de Almeida inflicted a crushing defeat in the Battle of Diu to the joint naval fleet of the Sultan of Gujarat, Mamluk Burji Sultanate of Egypt and the Zamorin of Calicut. It was a landmark event as it ensured European dominance over Asian seas, which would last for more than 400 years.

Francesco de Almeida Wikimedia Commons

Francesco de Almeida’s successor was Afonso de Albuquerque, who, in 1510, wrested Goa from the Bijapur Sultanate and established the seat of Portuguese State of India at Velha Goa (today’s old Goa) – marking the true start of Portuguese power in south Asia. At the time, Bengal (comprising present-day Indian states of West Bengal, Bihar, Odisha, Assam and the country of Bangladesh) was considered the richest province not just in the subcontinent, but in all of Asia. It was but natural that the attention of the Portuguese would soon fall on it.

The initial arrivals were private traders, who started visiting Chittagong port in the years after Albuquerque’s conquest of Goa. It was in 1516 that an official Portuguese fleet, under the command of Fernao Peres de Andrade set sail to explore the Bay of Bengal. The fleet was also carrying an official ambassador to China, so four ships were sent to Bengal led by João Coelho, which docked at Chittagong, then the largest sea port of the Bengal province. This was followed by the arrival of the first official envoy from Goa’s Portuguese governor to Bengal – João Silveira. It was Silveira who secured trading rights for the Portuguese in the Bay. Although relations worsened due to the Portuguese capture of two Bengal ships in Cambay, Silveira’s embassy was a critical turning point for the Portuguese in the region, enabling the foreign agency to establish a toehold in Bengal.

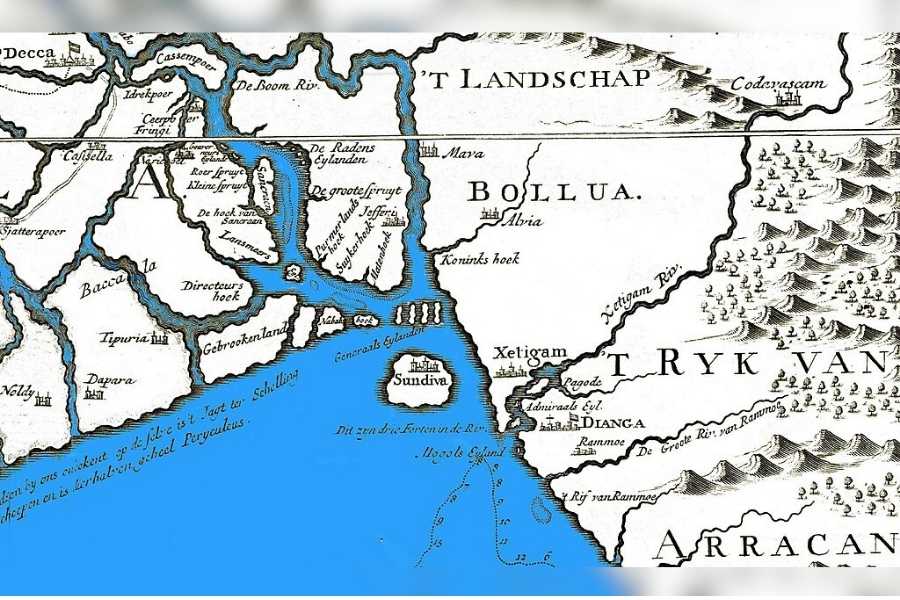

Wikimedia Commons

In the coming years, visit by Portuguese merchant ships became prominent at Chittagong, called Xatigan in Portuguese. Chittagong became their Porto Grande (Great Haven). In 1528, they built several more factories as well as a customs house here. Five years later, another Portuguese, Martim Afonso de Mello arrived with a hundred men in his ship and docked at Saptagram (Satgaon) in present-day Hooghly district – then one of the richest towns in Bengal. The province back then was under the rule of Ghiyasuddin Mahmud Shah, the last ruler of the Hussain Shahi dynasty. Afonso de Melo presented several gifts to the Sultan, but things turned sour when it came to light that the gifts were stolen commodities originally under the protection of the Sultan. Afonso de Mello and his countrymen were arrested and imprisoned on the orders of Ghiyasuddin. Some Portuguese buildings at Chittagong port were also set on fire.

When news reached Goa, the Portuguese governor dispatched a force to Saptagram by sea. A conflict seemed inevitable. Just then, the wheels turned once again. Bengal was then under attack from the Afghan warlord Sher Shah Suri. Ghiyasuddin realised he was in no position to fight on two fronts especially with an enemy who commanded the seas. Ghiyasuddin released de Mello and secured his help in dealing with the forces of Sher Shah Suri. Sensing an opportunity, the Portuguese acquiesced. The combined forces of the Sultan and the Portuguese secured a victory that saved Ghiyasuddin for the time being. In return, the sultan allowed the Portuguese to build factories in Bengal. More importantly, he conferred on Nuno Fernandes Freire and João Correa, the chiefs of the customs houses in Chittagong and Saptagram respectively, the right to collect customs duties.

The colonial age had arrived in Bengal.