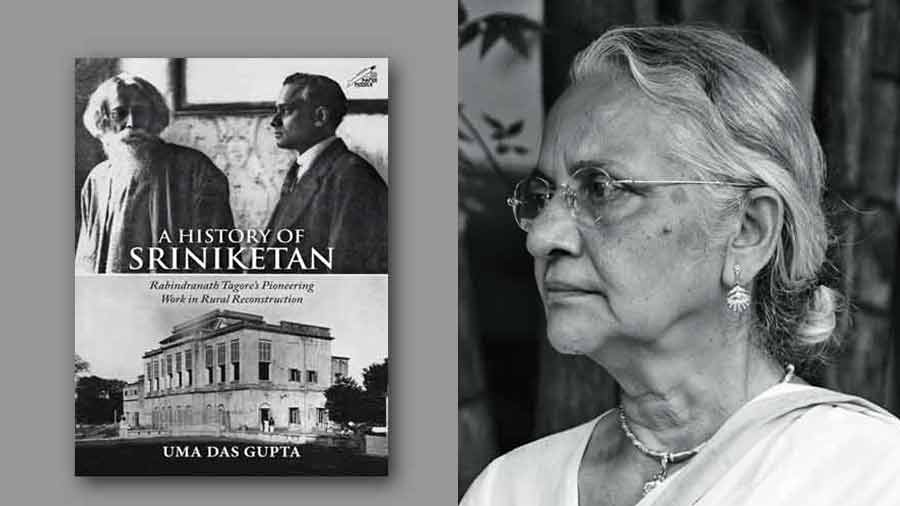

While much is known about Rabindranath Tagore’s contribution to art and literature, his work as a social reformer remains largely absent from public discourse. Which explains why, despite the booming tourism at Santiniketan, not many people are privy to his pioneering work in rural reconstruction at Sriniketan – a village that is barely 3km away from Santiniketan. My Kolkata talked to Uma Das Gupta about her newest book, A History of Sriniketan: Rabindranath Tagore’s Pioneering Work in Rural Reconstruction – which takes a deep dive into what Tagore came to call ‘The Sriniketan Experiment’.

Uma Das Gupta

Over a phone call, Das Gupta delved into the details of Tagore’s work in Sriniketan and shared why this rural reconstruction project was deemed by the Bard as his ‘life’s work’.

Edited excerpts from the conversation follow.

My Kolkata: Tell us about the inception of Sriniketan and your research….

Uma Das Gupta: Rabindranath’s own ideas of education and rural reconstruction were key to my research of Sriniketan. Among his many essays on these topics, some were autobiographical, recording how he turned to rural work in his family’s agricultural estate in East Bengal where his father – Maharshi Debendranath Tagore – sent him in 1889 as an estate manager. Rabindranath and his young family moved to Santiniketan in 1901 with plans to start a school for children in the heart of nature. And this is where the work of rural reconstruction began, first in the villages surrounding the Santiniketan schools, which were also in great decline, and later formalised through the institute.

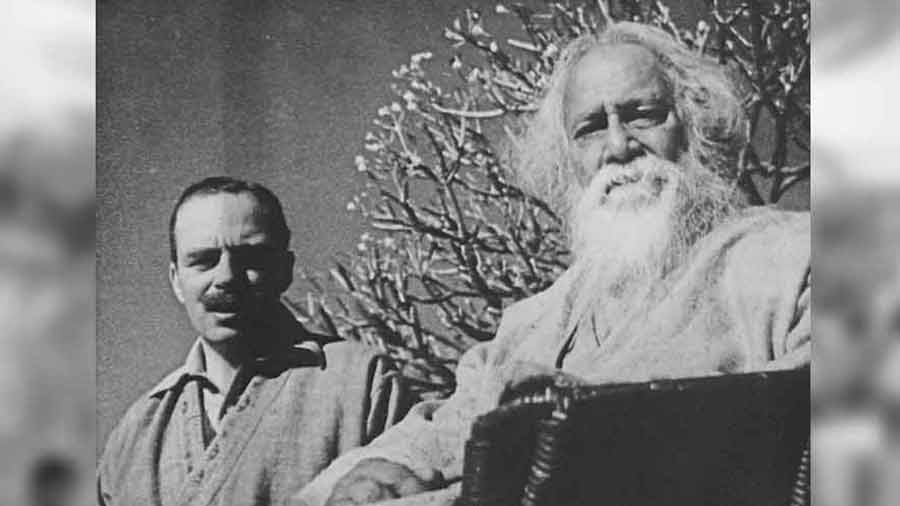

Among other correspondence between the leaders of the Sriniketan work, one will also find the charming body of personal letters between Rabindranath and British agricultural scientist, L.K. Elmhirst. Elmhirst came to Sriniketan in 1922 when the scheme was launched, and stayed just for two years before returning to his own work in England, but continued to keep in close touch with the Sriniketan team through the letters they exchanged. Tagore’s letters are among the Elmhirst papers in the Dartington Hall Trust archives in Devonshire, United Kingdom, and Elmhirst’s letters are in the Rabindra Bhavana archives at Santiniketan. Another important source of documentation were the diaries of Elmhirst, where one can find records of some day-to-day accounts of how the Sriniketan work was being carried out.

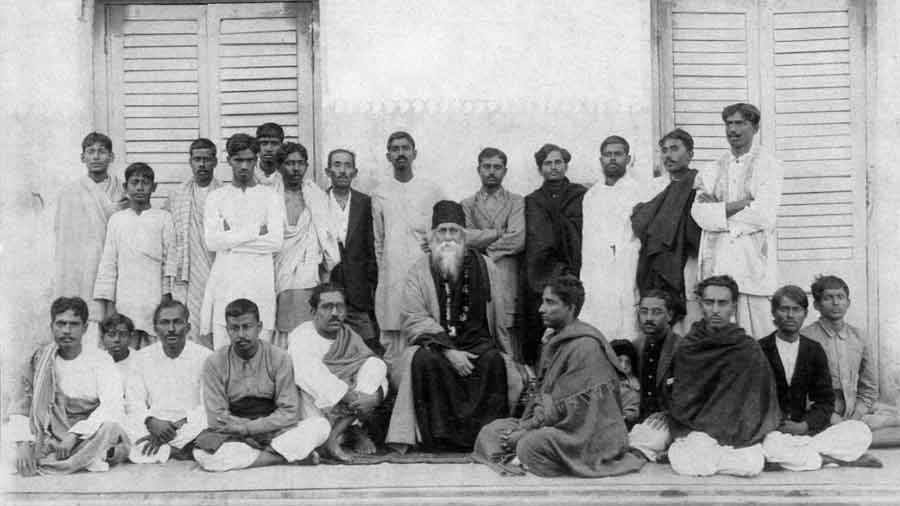

Rabindranath Tagore and L.K. Elmhirst

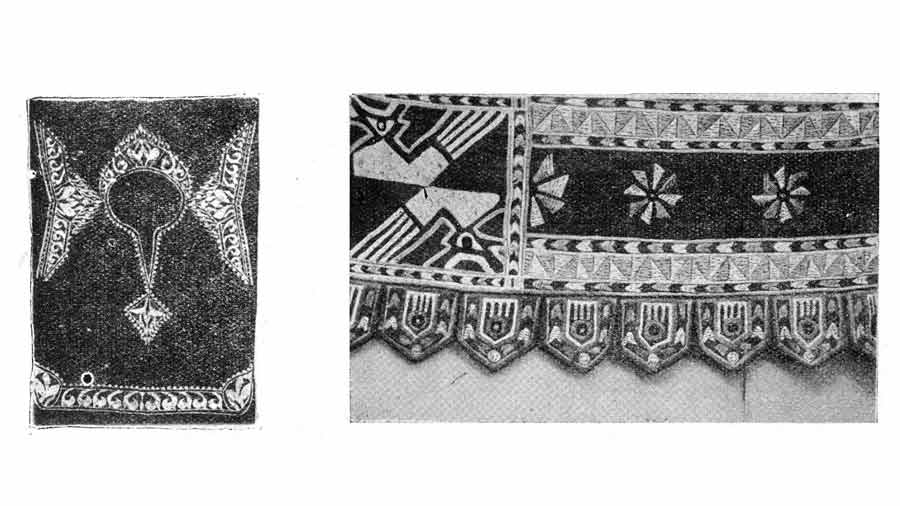

I have also included some of the path-breaking surveys conducted by Kalimohan Ghosh – another pioneer of the Sriniketan work – in the appendices of my work, alongside physical materials like statistical tables and graphs. Facsimiles of the photographs, bulletins and other archival materials have also been included in the book. The reproductions also included the art and crafts work done at Sriniketan.

Batik and embroidery work from the Visva-Bharati Catalogue of Sriniketan Handicrafts

After the 1950s, the pioneering work happening at Sriniketan slowly began ebbing away

What is the present-day condition of Sriniketan? Does it continue to reflect the vision of Tagore?

I wish I could say yes to that but I really can’t. After the 1950s, the pioneering work happening at Sriniketan slowly began ebbing away. Following the death of Tagore in 1941, the funding for the Sriniketan work began to dry up, because it was almost all private. Despite Tagore’s eldest son – Rathindranath – appealing to the independent government of India to do something for the institution, nothing happened. Soon after, in 1951, Santiniketan, Sriniketan and Visva-Bharati, along with all their schools and colleges, became one central university of the government, by the name of Visva-Bharati International University.

Rathindranath Tagore Wikipedia

As a result, pioneering projects like Sriniketan, had to be compromised owing to the various regulations of the government as well as the The University Grants Commission. So, it basically became more like a department, and did not completely reflect Tagore’s vision.

Tagore: If we merely offer them help from outside, it would be harmful to them

In one particular chapter, you’ve quoted from the record of the District Gazetteer which describes Tagore as being an honest and fair zamindar. Why then do you think the villagers still eyed the Sriniketan work with apprehension?

It was not that the villagers were apprehensive only about the Sriniketan work. Instead, it was a mentality that was absolutely endemic in them. Rabindranath wrote about this particular kind of experience with frustration, but also with his characteristic understanding and compassion, because he was deeply moved by the miseries of the villagers and wasn’t quick to criticise them.

In this regard, let me quote what Tagore said in his 1939 address to the Sriniketan Institute of Rural Reconstruction, “If we merely offer them help from outside, it would be harmful to them. So we have to think about how they could be stirred to life. It was difficult to help them because they despised themselves.… They would say we are dogs. Only ripping and beating will keep us right.”

The problem was that the villagers’ mentality was steeped in apathy and suspicion of the unfamiliar. They were used to demeaning themselves and this is what Tagore wanted desperately to get them out from. And of course, he blamed his own social milieu just as much for the villagers feeling that way, because they never felt accepted by the middle class.

Sriniketan landscape

Tagore: Speak to those with whom no one has spoken

In the final chapter of the book, you mention how Tagore was doing this work almost in isolation, with little to no support from the government. Why do you think there was this resistance from those in the upper, educated echelons of society? What were some of the criticisms that he had to face?

This is the product of a fundamental societal gap. It didn’t start with Rabindranath. There was always a gap between the elite classes and the common people of the land, and despite all his will and effort, it cannot be said that Tagore’s Sriniketan experiment made any difference in bridging this gap, which was created primarily by the accident of birth.

These people were almost born desperate and never quite got out of that despair. Neither did they seem to be too keen to get out of it.

The overall picture of late 19th century Indian society was such that peasants simply adhered to their traditions and did not change more than what was absolutely necessary. While the educated sections of society continued to hold them in contempt, Rabindranath knew from his life’s direct experience that things could not substantially change. Yet, however utopian the idea might have been, we still had to try.

Another thing that he pointed out was that the political scene at the time did not encourage feelings of belonging among the villagers. The political leadership obviously apprehended that recognising this vast multitude as their own people would force them to accept responsibility for them. This was where the Sriniketan effort was so valuable to Rabindranath – he thought it was essential and did not care that the nationalists criticised him. He saw to it that the Sriniketan work was at least able to establish a relationship with the village, which had not initially been the case.

There was a group of artists and journalists who visited Tagore during his later years at Sriniketan. He appealed to them to go and talk to the villagers, going on to say, “Speak to those with whom no one has spoken.”

Prime Minister Nehru at Sriniketan, 1952

Tagore: I continually endeavoured to find out how the villagers’ minds could be aroused

Did you gain any new insights into Tagore during your research for this work?

Before Sriniketan, Tagore had lived most of his life behind the tall walls of the Jorasanko house in Kolkata, and therefore did not have much idea about rural Bengal. When he first encountered rural life he wrote about how he realised the simplicity of these people, and that in turn, told me about his own humanity and compassion for the common people’s miseries. And that was a humanist insight that I needed.

Tagore wrote, “Gradually the sorrow and poverty of the villagers became clear to me. And I began to grow restless to do something about it. It seemed to me a very shameful thing that I should spend my days as a landlord, concerned only with money making and engrossed with my own profit and loss. From that time forward, I continually endeavoured to find out how the villagers’ minds could be aroused so that they could themselves accept the responsibility for their own life.”

Sriniketan students working in the fields

Frankly the book has had a moving and powerful effect on some readers, which is not very usual in the cut and dry history book that is mine. This is where I feel the insight of Tagore is conveyed and I’m humbled and glad that I have been able to communicate some of that inspiration from my narrative. For instance, a friend reading this book, wrote to me the other day saying how the image of Rabindranath Tagore, stepping down from his houseboat in Selidaha and going to shore at Sriniketan had reminded her of a quotation from the sixth chapter of Mark in the Bible, “As Jesus went ashore, he saw a large crowd and he had compassion on them for they were like sheep without a shepherd.”

This is what I meant. This is where Rabindranath’s insight must have resonated with the readers.

'Amra chaash kori anonde' holds up a mirror to his feelings about the village and its inhabitants

Tagore was deeply involved in and impacted by the work at Sriniketan. Is there any song in particular that was inspired by, or drew from his experiences at Sriniketan?

This question actually made me think a fair bit and I even tried to find out a bit more about it. It may have happened but might have slipped my notice, but he has written in Chinno Potro – which were the letters that he was writing from Selidaha, based on his rural experiences – about how he felt a parental affection of sorts towards the peasants, who he wrote “will never grow up.” So he had great compassion for the peasantry. And I feel that one song which is a classic Rabindrasangeet – Amra chaash kori anonde – reflected this love. It may not have been exclusive to Sriniketan but it holds up a mirror to his feelings about the village and its inhabitants.

The primary beneficiary of his Nobel Prize money would be the poor peasantry

You have mentioned in the book how Tagore gave his Nobel Prize money to be invested in rural credit instead of using it as an asset for Visva-Bharati. How was that decision received by the council members?

The Nobel Prize money was a significant amount, which was important for the staff and workers at Santiniketan as well, because they too were struggling to make ends meet. So naturally, they too expected to get something from it, and they did, but it was not as much as they had hoped. I would like to bring that down to a sense of gap in the community because if they really understood Rabindranath’s rural work, then the decision would not have come as a surprise to them. Tagore himself was in no doubt that the primary beneficiary of his Nobel Prize money would be the poor peasantry of his family’s estate, and that Santiniketan would only be the secondary beneficiary.

Tagore insisted that Santiniketan would only be the secondary beneficiary of his Nobel Prize money, after the poor peasantry of his family’s estate TT Archives

According to Prashanta Pal – Tagore’s biographer – who had access to the bank accounts, the total investment in the rural banks in 1914 amounted to Rs 75,000 of which Rs 48,000 would stay at the Patisar bank at 7 percent interest per annum and Rs 27,000 at the same rate of interest in the Kaligram bank. Tagore made it clear that only the interest from those investments would be used to pay for the maintenance of the Santiniketan school. There was no controversy about this – while it was definitely a disappointment, regardless of their personal opinions about the decision, nobody at Santiniketan or in Tagore’s close circle voiced this out of a deep respect for his vision.

Tagore’s hope was that someday, the Sriniketan work would be extended to other villages

In the final chapter, you write that Tagore wanted a complete awakening of the villager’s mind, which was a part of his ideal of rural reconstruction. His objective was to establish an ideal which might appeal to the country. How far do you think he was successful in doing this?

This is a very difficult question, albeit a legitimate one and I’ll try to do justice to it.

My personal opinion is that yes, an ideal was established, because empowerment of villages is now a nationwide project. How much has actually been done can be endlessly discussed but the fact remains that as a principle, it has been accepted and this is carried out by the panchayats. Of course, the government’s approaches are not and cannot be fully in character with Rabindranath’s vision. Adjustments have had to be made because of the demands of politics and economics of the times in which we are living.

But to expect the change to take place so quickly is unreasonable, especially after ages of neglect and suppression due to caste and creed, let alone the absence of education and the overwhelming poverty. There’s still a lot that can be done, and that I think, has to be recognised. Tagore had a right to hope for a complete awakening of the villages because hope must always be big. And he knew only too well, I’m sure, that this had to be a long-term goal. But he has gone on record multiple times to say that a beginning had to be made. This is where the work carried out by the Sriniketan experiment was significant even though it was done on a limited scale, and this is why Tagore was not apologetic about the small scale of the work. His hope was that someday, this work would be extended to other villages as well. He believed that a great deal could be done by ourselves, for our own people and he acted upon that conviction by way of making at least a beginning, and this is where he was calling in people of his milieu to break down that alienation that existed between the upper classes of our society and the common folks.

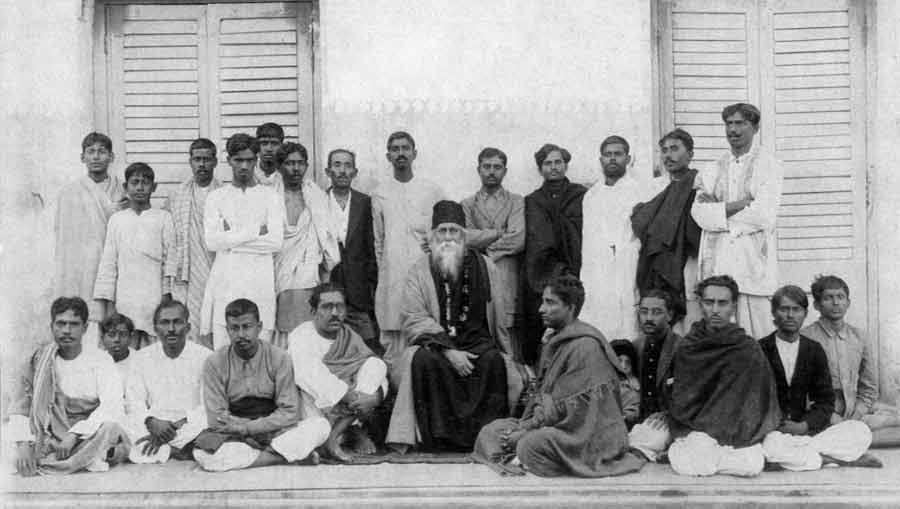

Sriniketan community with Rabindranath

He appealed that the Sriniketan work be just judged not by size, but by its worth. And I will end with a quotation from him which is important,

“I alone cannot take responsibility for the whole of India. But even if two or three villages can be freed from the shackles of helplessness and ignorance, an idea for the whole of India would be established. Fulfil this ideal in a few villages only, and I will say that these few villages are my India and only if that is done, will India be truly ours. Will India be truly mine. The scale of our enterprise will never be a matter of pride or even will never be a matter of pride to us. But let us hope that its truth will be”.

You have dedicated this book to your parents, who as you've mentioned, were among the pioneers of the Sriniketan work. Tell us a little bit about their role.

My father was an agricultural scientist by profession and went to England at a very young age, where he studied at the University of Wales, which had a famous agricultural school. And he returned to India between 1932 and 1933 after which he got married to my mother.

Tagore was always on the lookout for scientific agricultural expertise to implement in his Sriniketan project. So it would not be remiss to assume that he had put out the word for anyone who had returned to India with the relevant expertise and would be willing to aid in the work.

My father was invited by Rabindranath to come and serve in Sriniketan sometime in 1936-37, and the correspondence for the same is not only in our family files but also in the archives at Santiniketan. My father worked there for two years before he left to join the civil service, and was the first Dartington fellow of the Institute of Rural Reconstruction – a fellowship which was instituted by Elmhirst himself. My father was involved in the implementation of some of the agricultural expertise at Sriniketan, and so in that sense, in those early years, he was one of the pioneers of the work.

All photographs and captions [except for Rathindranath Tagore and Nobel Prize] are from: A History of Sriniketan: Rabindranath Tagore’s Pioneering Work in Rural Reconstruction by Uma Das Gupta and has been published by Niyogi Books.

Read more about the book here: https://www.niyogibooksindia.com