A faith meant for all mankind, now walled within its contradictions. A community that once built cities, now dwindled to a few hundred. A Tower of Silence, eerily quiet without vultures. This is the story of the Parsis of Calcutta — grand in legacy, yet fading in presence. A new documentary is receiving acclaim for exploring the community’s story. My Kolkata caught up with Vidhan Sharma, the director of They Have a Minute Left, and Prochy Mehta, one of its core contributors.

An unexpected fascination

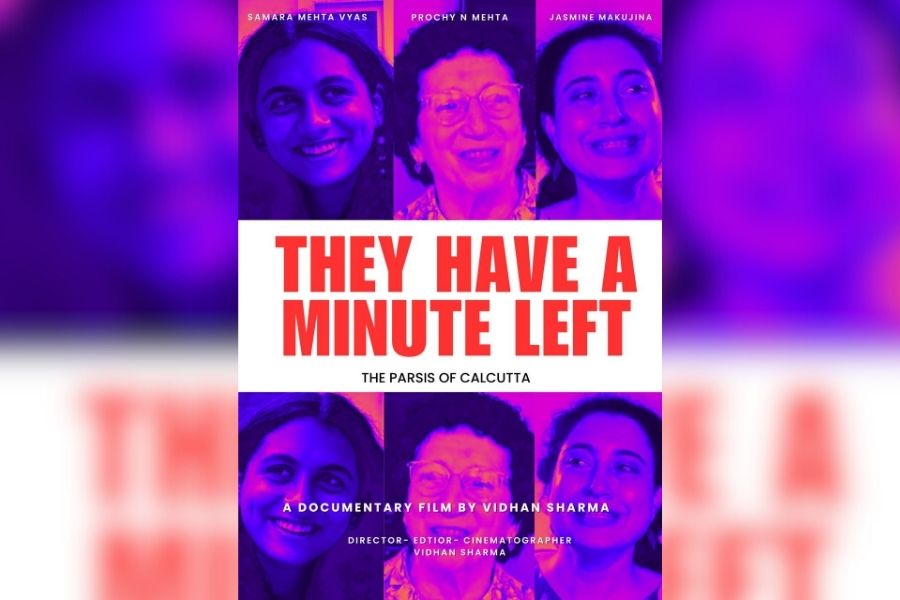

Through this documentary, Vidhan Sharma explores the deep-rooted legacy of the Parsi community while also questioning the rigid traditions that may be accelerating its decline. The film, told through the experiences of three Parsi women from different generations, recently won the Best Documentary Short Award in the National category at the Kolkata International Micro Film Festival 2025.

Vidhan’s fascination with Parsis goes back to his formative years at St. James’ School. It was his mathematics teacher, Yasmin Daraius Panthaki, who piqued his curiosity. “To me, Yasmin sounded like a Muslim name while Panthaki sounded like a Hindu surname. I would often wonder whether ma’am was Hindu or Muslim,” he recalls.

A few years later, while browsing the internet during the pandemic, he discovered that ‘Panthaki’ is actually a Parsi title. Intrigued, he reached out to her and asked if she was a Parsi. When she responded, ‘Yes’, his curiosity was further piqued. Vidhan had always found himself drawn to Parsi culture – from Boman Irani’s distinctive accent, to the story behind surnames like Postwalla and Batliwala. In 2022, when he returned to school, he asked Panthaki how many Parsis were left in Kolkata. “She stared at me for three seconds before replying, ‘Less than 500.’” The revelation had such an impact on Vidhan, that he felt a burning urge to document their story. “I feel very strongly about Parsi values that promote good deeds and words. Maybe I was a Parsi in a past life!”

Three perspectives

From the start, Vidhan knew that he wanted the narrative to follow three women from different generations. “Despite being an endangered community, there are several unfortunate practices within it that need to be talked about,” he said. Through their stories, the documentary raises difficult questions about ‘who is a Parsi’ and why certain customs persist despite their impact on the community’s survival.

Finding his subjects was a journey in itself. A mutual friend connected Vidhan to Samara Mehta Vyas, a student of La Martiniere for Girls. Samara’s story was particularly interesting, since she was a half-Parsi, who was denied entry into the Agyari (Fire Temple). Through Samara, he met her grandmother, Prochy Mehta, a respected scholar.

In May 2023, when he was done with his board exams, and was due to join Whistling Woods International, he decided to start the production of the film by interviewing Prochy and Samara. However, the third key figure to the story kept eluding him. Upon arriving in Mumbai, his coursework took over and the film was set aside.

Vidhan’s documentary has received praise from Cyrus Broacha, who is a Parsi himself

Last August, Vidhan felt an overwhelming desire to revive the project again. As luck would have it, a month later, he found himself in a documentary-making class with Jasmine Makujina, a visiting faculty at the institute. He showed her his tentative edit. “The moment the title card, Parsis of Calcutta, appeared on screen, she pressed pause, exclaiming, ‘Even I am a Parsi from Calcutta!’ I knew I had my third key!” he beams.

A week later, he was interviewing her. Jasmine provided rich insights not only about the practices within the community, but the prominent role they played in shaping Kolkata over the past century.

By mid-December, Vidhan’s final edit was ready. On January 19, he was at the Kolkata International Micro Film Festival. “Sometimes, you just need to wait for life to happen to you. I figured that the Parsi gods had blessed me.”

Who is a Parsi?

A critical topic examined by the documentary is the rigid structure that determines ‘who’ is a Parsi, through the journey of Samara Mehta Vyas, who is half-Parsi by birth

A major chunk of the narrative follows Prochy’s unfiltered views on the community’s internal struggles. “Parsis are the followers of Zoroastrianism, which is a religion meant for all mankind. The very tenet of the religion is to bring people into the faith, but Parsis have decided to discriminate within ourselves on various grounds,” she sighs. From interfaith marriages to the exclusion of women’s (and sometimes men’s) children, the definition of who is a Parsi varies across different trusts and groups. “The Government of India identifies us as a religious minority. Even as per our Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act of 1936, you cease to be a Parsi if you convert to another religion. The question is, how do you identify a Parsi?”

She recounts legal battles, such as the Saklat vs. Bella case of 1925, where the courts tried to define a Parsi based on attire and appearance. “You can’t identify a Parsi by face. There was even a ‘Parsi Nose Project’ because apparently, Parsis have big noses!” she adds with a laugh.

‘Every organisation can have a different interpretation of the term Parsi’

A major source of this is the community’s fluidity. Parsis aren’t bound to follow a religious leader, and are encouraged by their scriptures to listen to all sides and then make a decision. “The thing is, all Parsi institutions are governed by trusts, where rules are crafted by trustees. So every organisation can have a different interpretation of the term Parsi.”

A clear example of this is when Prochy’s own granddaughter was denied entry into the Agyari because she was not considered ‘fully Parsi’. “When my granddaughter was six, we were asked not to bring her in because the trustee said only Parsis are allowed. I asked, ‘Who’s a Parsi?’ That question led me to write my eponymous book.” Since Samara was denied entry into the Agyari, the entire Mehta family has stopped going too, but they continue to celebrate all festivals and occasions in accordance with Parsi traditions at home.

Prochy argues that this wasn’t always the case. According to her, these stricter norms are more recent than most believe. “Most of these strict rules came in because in the 1800s, Reverend John Wilson was converting Parsi boys to Christianity. So the rigidity came from this fear of Parsi boys leaving the religion. Similarly, DNA analyses have shown that most Parsi men came from Persia, but married Indian women. So conversions obviously happened,” Mehta adds.

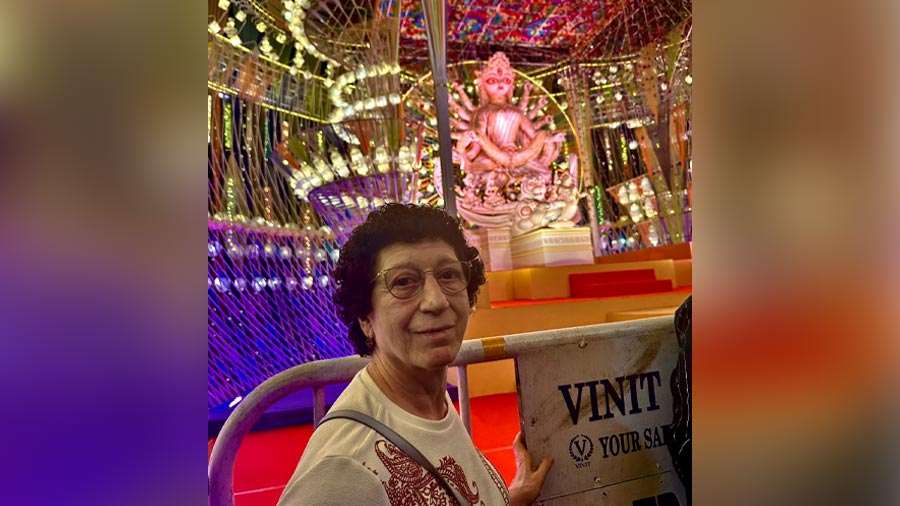

Prochy Mehta reflected upon how, despite being a dwindling community, the Parsis of Kolkata are very close-knit

She backs this up with the example of Suzanne Brière, a French lady who converted Zoroastrianism to marry Ratanji Dadabhoy Tata. “Her Navjote was performed by the community’s head priest at the time. And who was their child? JRD Tata!” She adds, “It’s a religion meant for all mankind. But if you keep telling people that they aren’t wanted, they won’t want you either.”

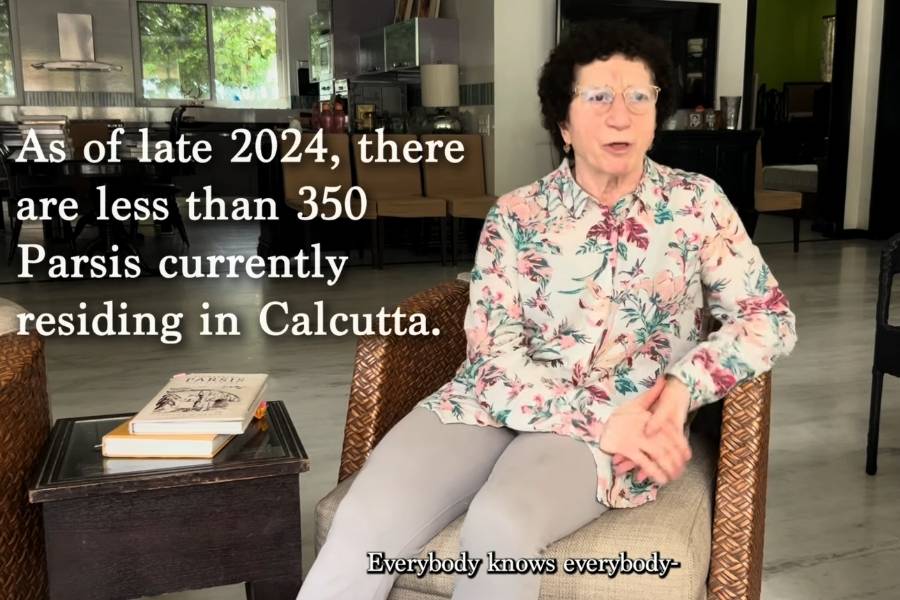

Beyond identity struggles, the Parsi presence in Kolkata has visibly shrunk, which was the focus of the documentary. “Back in the day, Kolkata had about 3,000 Parsis. When I was born, there were still 2,500. Today, we are about 350,” says Prochy. There are only about 40 Parsis under the age of 20 in the city. The younger generation has mostly migrated abroad, leaving behind an ageing population.

Caring for the elderly

Despite this, the community takes immense care of its elders. The Calcutta Zoroastrian Community's Religious and Charity Fund (CZCRCF) ensures that elderly Parsis receive medical assistance, companionship, and even go on outings. “Earlier, we had a bus that would take everyone to the mall, followed by the Calcutta Parsi Club for tea and snacks. The bus driver would even personally drop everyone home at the end of the day. But after Covid, things changed.”

It is this care and attention that has brought several ageing Parsis from around the world back to the city. The CZCRCF has also converted the Manackjee Rustomjee Dharamshala for Parsi travellers into an old-age home, moving in elders of the community who have no one to look after them.

Like most Parsis who have left the city, Jasmine Makujina often finds herself craving for the Kolkata she grew up in

The spirit of giving back is embedded in the community, who played a foundational role in building Kolkata. “Edulji Olpadwala had pledged his residence at 52, Chowringhee Road to CZCRCF. He ran out of money in his old age, and would sell artefacts from his house to survive, but not his house. Today, the community earns from that building,” Prochy says. She also talks about Rustomji Cowasi Banaji, who was influential in all sectors from insurance to banking to the ferry system.

Vidhan’s documentary doesn’t just dwell on loss; it also captures the infectious optimism of the Parsis. “Despite almost being on the verge of extinction, they are just so jolly! The virtue of being happy is something that I’ve learned from them.” He ends the film with a line that sums up this spirit: ‘There was never a Parsi, who went without letting a chuckle out from you...’

While the documentary is doing the rounds at festivals — receiving a selection at the South Asian Film Festival of Montreal — Vidhan is already thinking ahead. For the next chapter of They Have a Minute Left, he wants to explore another dwindling community: the Jews of India. His research is now focused on the Bene Israeli community in Kerala, tracing its origins.

For now, though, Parsis of Calcutta stands as an important chronicle of a community whose influence on Kolkata remains undeniable, even as its numbers continue to fade. Vidhan’s documentary doesn’t claim to have the answers, but it ensures that the questions are not forgotten.