Author-journalist Sahar Zaman was in Kolkata for Jashn E Mausiqui, a music festival at The Bengal Rowing Club that featured a tribute session to Talat Mahmood. The evening saw club members perform the singer’s ghazals and Bengali classics, rekindling memories of a voice that once defined romance on record and radio.

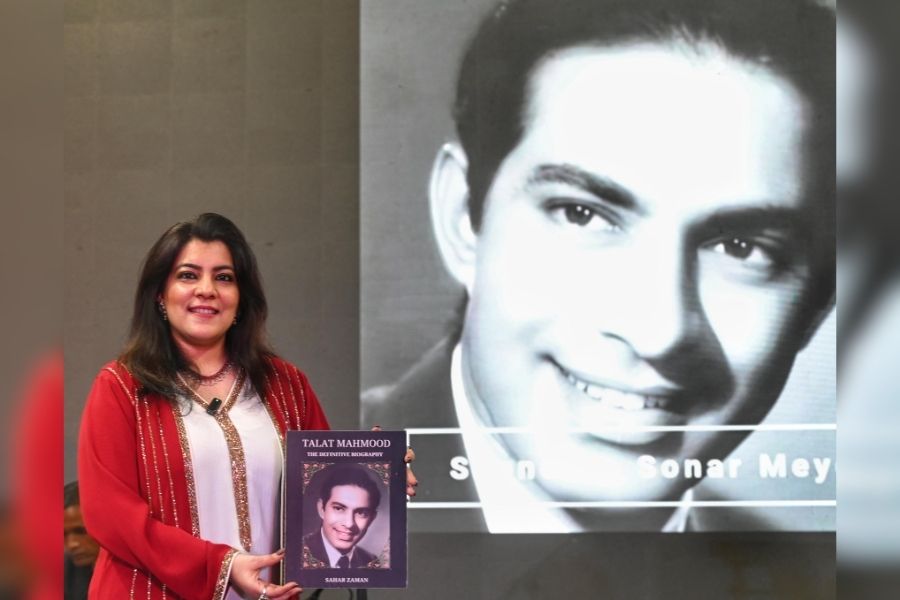

Following the event, Zaman sat down with My Kolkata for a conversation about the biography she wrote on her grand uncle, a book that began as a centenary tribute and has since grown into a cultural afterlife of its own.

“Since the book was released in 2024, I have travelled across the country with book talks,” she said. “It has been adapted into theatre, music shows and even dance productions. My idea was to celebrate his centenary, but we are in 2026 and people are still discussing his life. That tells me the story needed to be told.”

Why Kolkata remains central to his story

For Zaman, returning to Kolkata with the book carries emotional and historical weight. “Kolkata gave him his first stint of fame,” she said. “Before Hindi film music, he sang Bengali modern songs here under the name Tapan Kumar. And Kolkata also gave him the love of his life — he met his wife here.”

Even after success in Bombay, Talat Mahmood continued to return to the city. He recorded new Bengali songs, performed older ones and maintained a loyal audience. “He loved Kolkata and he loved his Bengali songs,” Zaman said. “Bringing the book here and speaking about his life in this city feels like a full circle.”

Writing family history without relying on family memory

‘I knew him as my grand uncle, not as the icon,’ said Zaman

Writing a biography on a family member came with its own challenges. “People assume it is easy because he was family,” Zaman said. “But I knew him as my grand uncle, not as the icon. He never documented his professional life for us. I had to reconstruct everything.”

That reconstruction demanded rigorous reporting. “Fact-checking became a habit,” she said. “If my mother told me something, I verified it with another relative. If a colleague from his music troupe told me a story, I cross-checked it with someone else from the same group. I did not even spare my family.”

Tracking down people from Talat Mahmood’s era was another hurdle. Many had passed away. Those who remained were in their nineties. “Finding them in time was the biggest challenge,” she said.

The concert tours that revealed Talat mania

Zaman signs her book

Among the most striking discoveries were stories from Talat Mahmood’s first concert manager, whom Zaman interviewed when he was over ninety. “He told me things that even we did not know within the family,” she said.

There were accounts of trains being stopped in East Africa so Talat Mahmood could perform for crowds that felt ignored. There were tales from the Caribbean, where backstage areas became so jammed that mounted police and helicopters had to clear space for him to reach the stage.

“It was hysteria,” Zaman said. “In 1968, while the Beatles were creating waves in India, Talat Mahmood was experiencing the same kind of mania in the Caribbean. These stories were too important to be lost.”

Switching off prime-time to enter a golden era

Perhaps the most personal challenge was stepping away from a 25-year career in television news to write the book. “Everyday news does not give you space in your mind,” Zaman said. “I stepped away from my studio for two years to live in another time.”

It required a complete mental shift. “My colleagues would discuss elections and breaking news. I would feel out of touch because in my head I was in the 1950s or 1970s,” she said. “But there was purpose in that break. I wanted to finish the book in two years.”

Returning to television news, however, held little appeal. “I do not want to spend my life discussing communal conflict,” she said. “Television news today spreads too much hate. I choose not to be part of that.”

The event was held at The Bengal Rowing Club

The challenges behind the velvet voice

Zaman’s book also explores the less-seen struggles of an artist’s life. “People see stardom as glamorous,” she said. “But artists live with constant uncertainty. Even after success, the question is always ‘what next’.”

She recalls one incident that captures the spirit of the golden era. Talat Mahmood was Dilip Kumar’s singing voice and was offered songs in the film Madhumati. “He asked the producers to give the entire film to Mukesh because his friend was going through a difficult time,” Zaman said. “That kind of generosity is rare today.”

As Kolkata once again echoes with Talat Mahmood’s songs, Zaman believes the book has achieved what she set out to do. “As long as people continue to sing him, his story remains alive,” she said.