If we agree that the Indian subcontinent has the world’s richest textile history, and within that story the region that is now West Bengal and Bangladesh has played the most significant part in creativity, quality, influence of ideas and techniques, economic benefit and global reach, then it is staggering that it has been so inadequately studied.

Now, Darshan Shah is leading an ambitious project to put that right. In 2020, her well-established Weavers Studio Resource Centre (WSRC), based in Kolkata, started a comprehensive study of the textiles of undivided Bengal from the 14th century until today. The first manifestation of their findings is now taking place in three separate yet complementary ways: an exhibition, a symposium, a book.

Textiles from Bengal: A Shared Legacy is a dazzling gathering of masterpieces for all to enjoy. It is the first to focus on hand-woven and hand-patterned textiles from across this region. If you thought you were familiar with fine Bengali textiles, think again and hurry along to Kolkata Centre for Creativity where it’s on show until 31 March. Shah says she and her team whittled down their draft exhibition list of about a 1,000 star pieces to 120 super-stars. Most are on show for the first time and have never even been published.

Mayank Kaul, exhibition curator, has deftly arranged them into nine themed sections. Three introductory ‘hero pieces’, as he calls them, sum up what will follow: a huge reversible kantha embroidery lent by the legendary Tapi collection formed in Surat and Mumbai – they have lent 17 pieces in all; a length of fine cotton woven in Dhaka in the late 19th century, part of WSRC’s own growing collection; and a large rumal, or canopy, with all-over metallic jamdani, made at the turn of the 18th-19th centuries.

Before plunging in to the feast of textiles, some samples from Thomas Wardle’s 1866 swatch book made mostly in ‘Dacca’ but also in ‘Santipore’ and ‘Moorshedabad’ – their quality described as shubnam (evening dew) or abrawan (running water) – reveal why Bengal could do textiles so well. The geography and climate were ideal: cotton and jute thrived on the fertile land of the world’s biggest delta, while wild silk came from forests to the north and indigo, the most successful of blue dyes, grew on the delta sandbanks. And the humidity of the tropical climate enabled extremely fine yet sturdy muslins to be woven – and still does. Rivers had provided cheap access through north India and to the Bay of Bengal for trading textiles since early times; Kautilya wrties in the 4th century BC about an established industry.

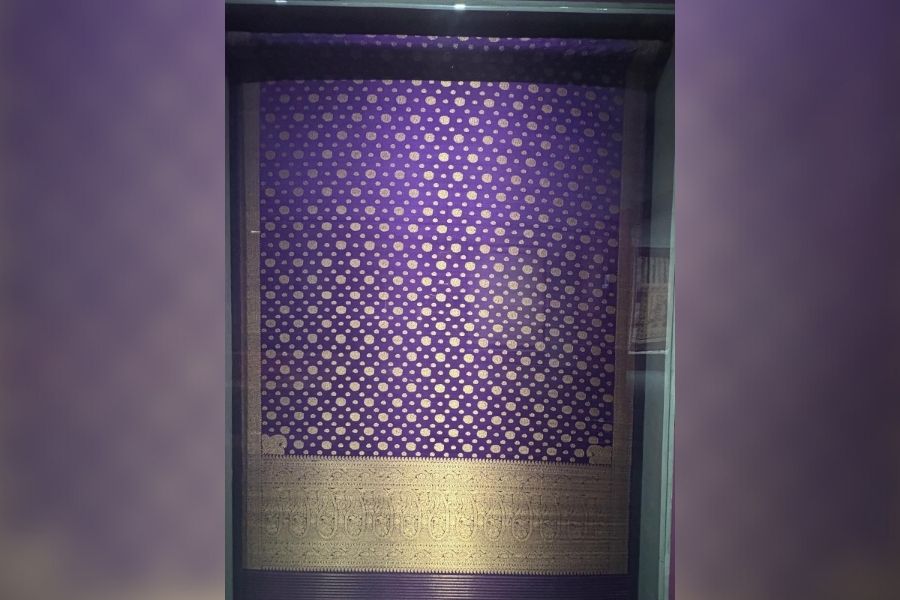

There follow galleries displaying silk embroideries for the lucrative Indo-Portuguese trade, ‘haji rumals’ bought at Bengal fairs by pilgrims going off to Mecca, and utilitarian kantha made by women at home and now enjoying a successful revival. One group shows how Murshidabad’s baluchari is at the root of Varanasi’s rich Banarasi brocades, and two lavish brocade saris demonstrate this constant weaver, ideas and skills migration: one was made in Varanasi in the early-mid 20th century, the other was woven in Mirpur, Dhaka in 2024 by Mohammad Kutubuddin, a third-generation weaver whose family migrated there after partition. Along the way there are reminders of the cosmopolitan communities that textiles were serving – locally from Marwari and Parsi to Muslim, Hindu and Christian, globally from Dutch, French and British to Chinese and Armenian.

A pilgrim’s cloth, or ‘haji rumal’

Not surprisingly, three sections are devoted to jamdani, the renowned tradition of brocading that became the ultimate fashion statement in Indian courts and the Western high society. First, there is a gallery devoted to the lesser-known multi-coloured jamdani saris with grid, diagonal, wave and floral designs that feel utterly contemporary. Ruby Palchoudhuri, trailblazer for Bengal textiles, has lent her 19th-century cotton sari of bold saffron, green and red floral designs woven in Dhaka. Nearby, two pieces demonstrate how today’s Indian designers are steeped in their textile heritage and pushing the boundaries ever further. Chinar Farooqui of Injiri has lent a piece with her signature multi-coloured jamdani mosaic scattered across fine white cotton. Bappaditya Biswas’s dramatic white coat of cotton, felt, silk organza, viscose and zari plays with the versatility of traditional jamdani. As he explains: “The weaving technique of extra weft jamdani is what links us to the past and the concept of creating a garment on the loom with bold motifs and unconventional materials used as extra weft makes this a contemporary piece.”

A silk zari sari from Bangladesh

The next two galleries deliver what we expect from jamdani: white-on-white, gossamer-fine, translucent muslin with decoration reflecting a refined aesthetic, the pinnacle of south Asian textile sophistication. Looking at the pieces, you hold your breath before their delicacy lest you blow them away like a fluffy seedhead. Here, find two angarakhas and a patka, all made in 19th century Dhaka, and some children’s caps and a woman’s dress from Murshidabad. A woman’s jacket touches again on the intriguing subject of migration of techniques and weavers. Its label states frankly that there is much to learn: ‘Origin unknown, in Bengal or Lucknow in Uttar Pradesh, India (made for the Murshidabad market, 19th century)’.

The thrilling two-day symposium that followed the exhibition’s opening confirmed how the deep study of Bengal fabrics is indeed in its relative infancy. Speakers shared their research, mostly unpublished, with the repeated refrain ‘I have more questions than answers’, inviting researchers to come forward and delve in (write to projectundividedbengal@gmail.com). However, the triumphant first book to be published in WSRC’s great study, Textiles from Bengal: A Shared Legacy, gets going on finding answers to both obvious and offbeat questions. More than 50 essays discuss subjects ranging from blue dye, Bhagalpuri silk and Jain merchants to textile labels, Nandalal Bose’s batik and the Danish-Norwegian trade with Bengal. It seems that few lives have remained untouched by Bengal textiles.

One evening, Ms Shah masterminded what could perhaps be called an experiment in textile opera. In front of a backdrop movie of wafting textiles and dye-dipping, the Bengali-British musician and composer Souvik Datta sat high on the stepped performance stage to play specially composed ragas on sarod that flowed in sympathy with the three craftswomen sat on lower steps patiently stitching their madhubani, shibori and kantha cottons. Either side, two textile printers prepared their designs. It worked wonderfully.