Heavy rains have left north India reeling, with floods submerging roads, washing away houses, and pushing rivers over their danger marks. Punjab, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Jammu and Kashmir are among the worst hit this monsoon..

Punjab has reported at least 29 deaths and mass displacement in what state officials describe as the “worst flood in recent history.” The state recorded 253.7 mm of rain in August, 74 per cent above normal and the highest in 25 years.

Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand are also reeling from landslides and flashfloods triggered by incessant rain, deadlier than what these Himalayan states are used to.

A damaged portion of the Gangotri highway following flash floods and landslides triggered by a cloudburst, in Uttarkashi(PTI)

Delhi and the national capital region are on edge with the Yamuna above the danger mark.

The Indian Army’s Western Command has activated 47 columns, including air force helicopters, rescuing more than 5,000 civilians and delivering 21 tonnes of relief material in Jammu, Punjab, and Himachal Pradesh.

Why are the floods so bad this year?

The changing climate is a key driver of this intensification,.said climate scientist Dr Roxy Mathew Koll, lead author of the IPCC Reports and former chair of the Indian Ocean Region Panel.

“A warmer atmosphere and warmer surrounding seas are loading the monsoon with more moisture; when that air is forced up the Himalayas – and the Western Ghats too – it can result in very intense rainfall over small catchments,” Koll told The Telegraph Online.

An ambulance skidded off the Kiratpur-Manali highway and fell down a slope, in Mandi(PTI)

He explained that the monsoon baseline has shifted toward fewer rainy days but heavier bursts, with higher atmospheric moisture and more short-duration extremes.

“Landslides and flashfloods also reflect what we do on the ground...slope cutting, road building, deforestation, construction on debris fans and floodplains, and clogged drainage convert heavy rain into destructive runoff,” he added.

“The risk envelope has moved upward, making clusters of flashfloods and landslides more likely in seasons with strong moisture surges.”

The way forward, he said, lies in dense monitoring networks, open real-time data, radar-based nowcasting for cloudbursts, and strict land-use controls on floodplains.

His research highlights the scale of the challenge.

Between 1950 and 2024, India recorded 325 flooding events that affected 923 million people, left 19 million homeless, and killed around 81,000.

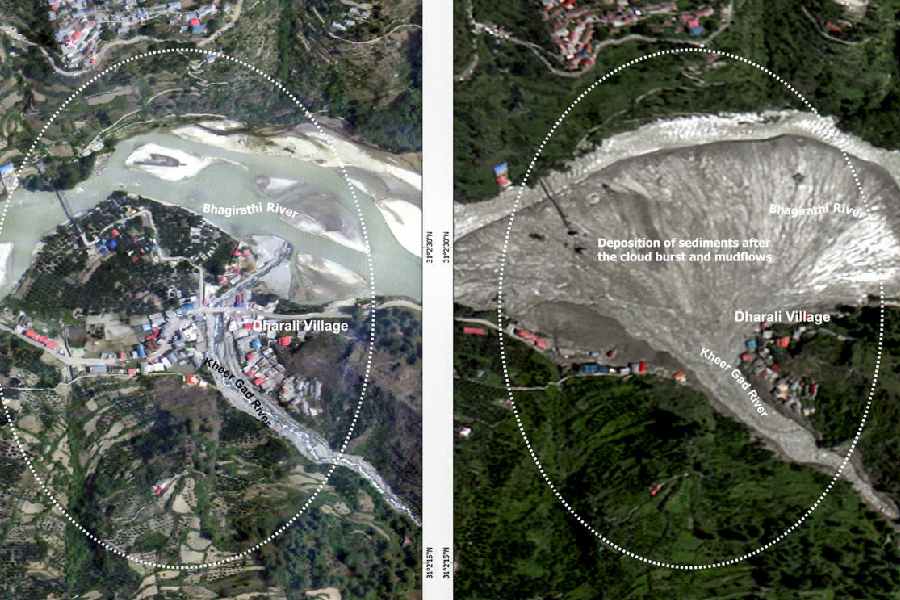

In this satellite image released by @isro via X on Aug. 7, 2025, Dharali village and surroundings before, left, and after the clouburst-triggered flash floods, in Uttarkashi(PTI)

“The rise in extreme rainfall events is over a region where the total monsoon rainfall is decreasing. The fact that this intensification is against the background of a declining monsoon rainfall makes it catastrophic, as it puts several millions of lives, property and agriculture at risk,” Kolli said.

This year’s monsoon has also been marked by regional contrasts.

Rajasthan and Gujarat have received significantly higher rainfall, while the northeast has seen much less. Though India’s overall average rainfall has declined in recent decades, extreme rain events have become more frequent, studies say.

Extreme rain, glacial lakes swell

Researchers at IIT-Bhubaneswar studied rainfall data from 1991 to 2022 across northwest India’s arid and semi-arid regions. Using high-resolution datasets from the India Meteorological Department (IMD), they found a rising frequency of extreme rain events and linked them to shifts in dominant meteorological drivers.

The Central Water Commission (CWC) too has raised alarm over the rapid expansion of Himalayan glacial lakes, which threaten to unleash sudden floods downstream.

Security personnel rescue an elderly woman from a flood-affected area following heavy rains, in Srinagar(PTI)

In its June 2025 report, the CWC said 432 glacial lakes across Ladakh, Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Sikkim, and Arunachal Pradesh have grown in area and “demand vigorous monitoring for disaster purposes.”

“The total inventory area of Glacial Lakes within India was 1,917 hectares in 2011 which has increased to 2,508 hectares in 2025 (June). There is a 30.83 per cent increase in area,” the report said.

A view of a waterlogged area at IIIM Hostel after heavy rainfall, in Jammu(PTI)

Overall, 1,435 glacial lakes expanded across the Himalayan belt in June. Arunachal Pradesh accounts for the highest number, followed by Ladakh and Jammu and Kashmir.

Raising serious concern on the issue of ecological imbalance in Himachal Pradesh, just last month the Supreme Court had said that the day is not far when the entire state may vanish in thin air from the map of the country. “God forbid this doesn’t happen,” the court had said.