Not too many viewers of Hindi cinema — nor every reader in the Bengali language — know Nabendu Ghosh by name. But whether they do or not, his work has surely touched their lives unknowingly. For, he is credited with scripting classics of Indian cinema such as Devdas, Sujata, Bandini, Abhimaan, Aar-Paar, Laal Patthar, Teesri Kasam, Trishagni….

And his literary oeuvre? Legendary filmmaker Mrinal Sen sums it up thus: “As a writer and a creative individual, Nabendu Ghosh has never believed evil is man’s natural state. Along with his characters he has been confronting, fighting and surviving on tension and hope.”

Had life followed his plans, Sen’s first film would have been Aajab Nagarer Kahini (Tales of a Curious Land), Ghosh’s novel — an allegory about human society and political ideology which is considered a seminal work in Indian literature by scholars, writers and readers in Bengal and Bangladesh — that Bimal Roy too was keen to film in 1948 before Pehla Aadmi.

Although he did his MA in English (1939, Patna University) and spent more than 50 years on the shores of the Arabian Sea, Nabendu-da, as he was known to his industry colleagues, readers and cinema students, never stopped serving Bengali literature. He started while in school and by 1940 was recognised as a star in Kolkata’s literary circle. Daak Diye Jaai (The Clarion Call), set against the Quit India Movement of 1942, catapulted him to fame, but in 1944 he lost his government job for ‘seditious writing’ and in 1945 he shifted to Calcutta. The 1940s were a period of turmoil, and drawing upon the trauma unleashed by the famine, the second World War, the freedom struggle and the communal riots, Ghosh became the foremost voice among progressive writers. The unmatched diversity of his characters also came from his being born in Dhaka (March 1917), belonging to Bengal but raised in Bihar, living in Bombay that got divided into Maharashtra and Gujarat.

Ghosh became a member of Bimal Roy’s team when the legend himself was trying to relocate to Bombay. This was right after the Partition which proved a tremendous setback for the arts in India. With Urdu being declared the official language in newly-founded Pakistan, Bengali books were banned in the erstwhile East Bengal. Cinema too was grappling with the economic crisis unleashed by the halving of viewers. New Theatres was in doldrums, having lost its Lahore studio to politics and much of its early treasures to a fire. Bombay Talkies was not better off either. The first 10 months after their arrival in the financial capital the team did not get any pay. Maa — which had drawn them to Bombay — showed no sign of taking off. At this point established producer S.H. Munshi proposed to adapt a Maupassant story and Baap Beti was made, providing the entire team short-term relief and a foothold in Bombay. Ghosh shouldered responsibilities for the film’s literary qualities and forged a lasting equation with the producer. And the bonding with Bimal Roy was cemented by subsequent films Parineeta, Biraj Bahu, Yahudi, Devdas, Sujata, Bandini….

The art of screenplay

Ghosh became a legend in screenwriting through his association with Roy and every other maestro of the 1950s, ’60s and the ’70s — Guru Dutt, Vijay Bhatt, Phani Majumdar, Gyan Mukherjee and Satyen Bose to Raj Khosla, Prakash Mehra, Lekh Tandon, Asit Sen and Dulal Guha, not to mention Hrishikesh Mukherjee or Basu Bhattacharya. But Ghosh never stopped writing novels and stories that are now treasures of Bengali literature. His autobiography Eka Naukar Jatri (Journey of a Lonesome Boat, 2008) describes his life as “a train running on two parallel rails of literature and cinema — one in Bengali, the other in Hindi”.

If he scripted films for directors who were shaping what would soon be the world’s biggest industry, Ghosh penned stories that he posted to publishers in Calcutta and, periodically, published as anthologies that mirror the transition in our civic, political and moral life. This continued till he reached the ripe age of 90, with 28 novels, 15 story collections, and the West Bengal government’s Bankim Puraskar to his credit. Sadly, despite their richness in terms of content, structure, social documentation and philosophic relevance, Daak Diye Jaai, Aajab Nagarer Kahini or Phears Lane never became textbooks of Bengali studies. By all accounts, this was because he came to be seen only as a screenwriter.

No one denies the significance of a good screenplay. If most Bimal Roy classics were scripted by Nabendu Ghosh, Raj Kapoor’s major productions were fleshed out by writer-director K.A. Abbas, while Guru Dutt gained immensely from the literary merit of Abrar Alvi’s screenplays. Such instances abound even before we come to Vijay Anand, Gulzar or Salim-Javed, who were among the first to be projected as ‘stars’ of a film.

Hollywood recognised the importance of screenplays long ago. The Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences Academy gives two Oscars: one for the Best Original Screenplay, another for the Best Screen Adaptation of a published work. Unfortunately in India, few cinegoers know what a screenplay is. In such a scenario, it is hardly surprising that, barring stray examples of Ray and Sen, you come up with nothing if you go looking for screenplays.

Still, Nabendu Ghosh continues to command respect, from stars and filmmakers to litterateurs and historians. A look at the body of work born of his pen explains why a postgraduate student of Banaras Hindu University is completing his dissertation on ‘Nabendu Ghosh’s Novels and Contemporary Politics’. And actor Reeta Bhaduri, an FTII alumni who acted under his direction in Ladkiyaan, dubs him “the godfather of screenplay writing”. Even today, directors entering the field can learn from him, she says, because ‘he puts in so much ingredient, and in such a lucid manner, that a director only needs to say, “Action!” and “Cut!”’

He put soul in his scripts: Hrishikesh Mukherjee

Hrishikesh Mukherjee and Gulzar, both gurubhais from Bimal Roy’s school who are Dadasaheb Phalke winners, have lauded Ghosh’s stature. “He put soul in his scripts, as is evident from both the films he wrote for me — Manjhli Didi and Abhimaan,” said Hrishi-da, who had a silent regard for him since their early days in Bombay when they shared a room in Malad and many moments of joy and sorrow. And Gulzar Sa’ab acknowledged him as his ‘guru’ who led him by his finger into screenplay writing. “I learnt about developing situations and characters as Nabendu-da discussed these with Bimal-da and even had heated disagreements regarding the ending of Bandini,” he said. These inculcated in him certain (humanitarian) values that are a strong point of the tradition now called the ‘Bimal Roy gharana’.

Summing up the impact of a script on a director, Govind Nihalani says, “To Bimal Roy, Ghosh was a literary asset. This was proved time and again by Devdas, Sujata, Bandini. Nor will Teesri Kasam let me forget his contribution to Indian cinema. It is a landmark in the art of scriptwriting.”

Devdas

Devdas, a classic by every count, is not the only Sarat Chandra novel Ghosh adapted for the silver screen. Prior to that he had written Parineeta and Biraj Bahu for Roy, and subsequent years found him writing Manjhli Didi and Swami. Ghosh was drawn to Sarat Chandra as a school-going child, through the banned Pather Daabi, and from the outset of his screenwriting career he found his situations, characters and emotions totally in sync with our cinema. “It easily connects our society with our viewers,” he’d say.

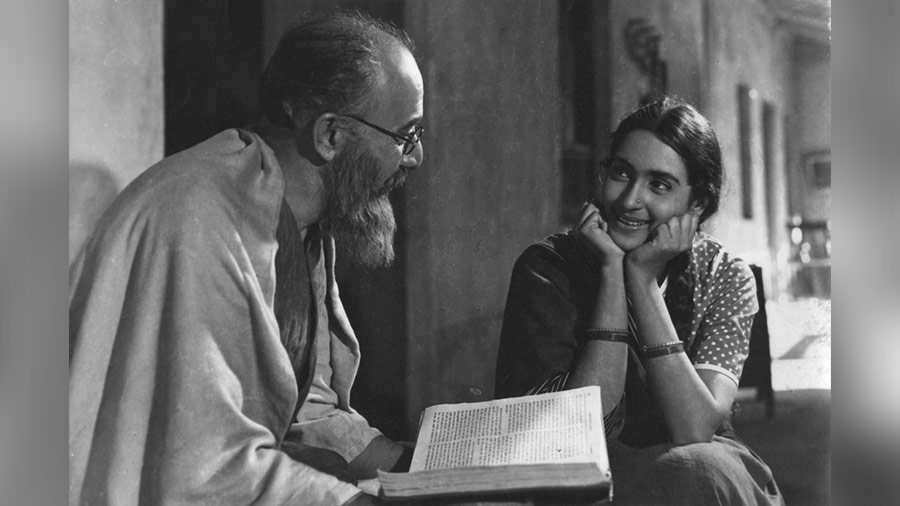

A still from Bamdini (1963). IMDb

Bandini

Bandini, based on a novella by Bengali writer Jarasandha, delves into lives condemned to languish behind bars; and lives resolved to sacrifice personal pleasures for their motherland. Bikash’s commitment as a freedom fighter stops him from marrying his betrothed – and the intensity of that love prompts the Vaishnavite Kalyani to kill her rival in love. The screenplay fully extracted the story’s scope for drama, emotion and songs.

Sujata

Sujata, based on a short story by Bengali litterateur Subodh Ghosh, was a strong indictment of untouchability. Apart from the nuanced interplay of characters and emotions, the script played up the twist of blood transfusion that negates the whole concept of ‘low born’ – achhut – and shows her to be ‘born noble’ – sujata.

Teesri Kasam

Teesri Kasam, based on Maare Gaye Gulfam urf Teesri Kasam by Hindi novelist Phanishwar Nath Renu, won the Golden Lotus 1966. The build-up of motley characters in a mela, the atmosphere in a nautanki, the rootedness of the poignant songs in the milieu, and the finale where the protagonists go their separate ways carrying only the memory of unarticulated love: all this rightly places the film among the finest examples of adapting literature to the screen.

Trishagni

Trishagni, based on Maru O Sangha by Bengali author Saradindu Bandopadhyay, revolved around two monks and two youth growing up in a remote monastery in Central Asia some 2,000 years ago. It is among the few films that dramatically approach the tenets of Buddhism. The challenge for the screenwriter lay not only in adapting a short story into a full-length feature film – it was so for Teesri Kasam, Sujata and Woh Chhokri too. Going back in time to recreate a period lost in the haze of history was a mightier challenge. Trishagni remains unique in exploring the conflict that besets even man of faith, be he a worshipper of Buddha, Allah, God or Bhagwan. This was a core area of interest for Ghosh who wanted to do a trilogy dissecting such conflicts in three different philosophic settings.

Script to Screen

Did this masterly grasp over his art emanate from the fact that he came to cinema from literature, which he was inducted into via his school’s handwritten magazine Jharna, and remained his first love right until the end? But his autobiography also records his love for moving images since his schooldays in Patna, when he and his friends would frequent a humble ‘Lucky Cinema’ to watch Douglas Fairbanks and other attractions of the silent era with savings from their tiffin money. Did his writings work in favour of his becoming a screen playwright? Or did writing for the screen mould his extremely visual narrative

In his stories the incidents and chain of events unfold in such a manner that readers feel they are witnessing it take place in front of their eyes. Bimal Roy had noticed this quality when he asked the writer to join him. Nabendu Ghosh is always present in his stories as an observer, watching the action unfold sometimes as a friend (Bharat Gupta series), sometimes as a crow (Kaak Bhushandi Katha), a monkey (Aranya), a ghost (Papui Dweeper Dhwansha Katha), or the omnipresent moon beaming down on the players (Chaand Dekhechhilo).

Perhaps, then, the two parallel rails were divergent branches of the same tree of creativity!

Ratnottama Sengupta, the daughter of Nabendu Ghosh, is a film journalist and author