I don’t have much knowledge yet in grief

So this massive darkness makes me small.

– Rainer Rilke, ‘Pushing Through’

The call… it’s not just a parent’s worst nightmare. No parent can countenance the eventuality. Not even in a bad dream. It is unthinkable. Unspeakable. Unmentionable. No wonder the English language does not have a word for it. A man who has lost his wife is a widower. We have widows, orphans, bachelors, spinsters, adulterers, even words for women or men who cannot have children. There is, however, no word in the English language for parents who have lost a child. It is as if language itself refuses to acknowledge the terrifying nature of the condition.

This is the terror, the despair that Mahesh Bhatt’s unflinching 1984 take on grief and loss, Saaransh, explores. Fresh from the commercial and critical success of Arth (1982), a searing evaluation of relationships of another kind, Bhatt gave us this bleak and despondent tale of parents coping with the loss of their only son. If Arth burns with the intensity of love, hate and betrayal, Saaransh leaves you gutted with what I think of as cold fire.

The story of the film is too well-known to bear repetition. Forty years on what stands out is how relentless it is, how unsparing, in its exploration of grief. From the first sequence when an elderly man wakes up in the middle of the night and walks over to a desk to write a letter to his son who is no more – we have the dreadful ringing of the phone and a short slow-motion flashback to the ‘call’ – the director has you by the scruff of the neck and won’t let go.

Like the autumn leaves that blow across the pavements in the haunting ‘Andhiyara gehraya, soonapan ghir aaya’, rendered in Bhupinder’s sonorous voice – uncanny how the song, and three words in it, ‘ghabraya mann mera’, convey a foreboding that informs the narrative – the film leaves you with a sense of decay, disrepair that has no possibility of rejuvenation. Unlike an overwhelming majority of films of the era marked by songs and dance and comic interludes that often diluted their ‘serious’ statement, if any, Saaransh offers the viewer no escape. It’s like going through an emotional wringer. The only other film that comes to mind that has the same emotional effect is Robert Redford’s Ordinary People (again dealing with the death of a child and the effect it has on a family).

Saaransh is possibly among the first Indian films, definitely Hindi films, that explicitly deal with issues of loneliness and depression among the elderly, how hostile the world can be to them even in a society like ours that prides itself on being sensitive. As also a rare film that openly talks of suicide as a way out.

This is underlined in the character of Pradhan’s friend whose wife passed away 30 years ago. He has a unique bond with Pradhan and Parvati, where they share loneliness and companionship. As Pradhan says in a touching scene referring to him: ‘He used to be a friend at one time. I don't know what he is now.’

Early in the film we have the protagonist walking in front of a speeding car, and surviving by a whisker. Coping with the grief of his son being mugged to death in New York, B.V. Pradhan goes through a similar experience in a subway in Mumbai. Broken, humiliated (as much by the experience as by life), he first eyes the bottle containing the iodine tincture being applied to his cuts and bruises and, when he cannot find it at night, locks himself up in his kitchen and throws open the gas stove.

Saved by the timely intervention of his tenant Sujata and her boyfriend Vilas, he rants about not allowing life to humiliate him anymore, about the one right no one can deprive him of, the right to take his own life.

The second half of the film, with the entry of Sujata and the discovery that she is pregnant, enters the thriller territory so to speak. And features some of the most nerve-racking sequences put on screen as the politician Gajanan Chitre unleashes terror on the elderly couple and Sujata. This too is brilliantly handled with Chitre’s goons (played by an array of then popular TV stars, including Salim Ghouse) terrorising Pradhan and the narrative providing no respite from the mounting tension. A few years down the line, Tapan Sinha’s Atanka would revisit a similar terror on another schoolmaster character and his family.

Of course, the cornerstone of Saaransh’s enduring reputation lies in Anupam Kher’s performance as B.V. Pradhan, surely among the finest in the annals of Indian cinema. In Pradhan, we have one of the most memorable male protagonists of Hindi cinema, comparable to Amitabh Bachchan’s Vijay and Om Puri’s Anant Velankar, among others. It is remarkable that this was his debut feature and that he was only 27 at the time. Even more remarkable is the fact that he was almost replaced by Sanjeev Kumar at the last moment at the insistence of the producers who wanted a bigger name.

However, good sense prevailed, and though there’s no doubting Sanjeev Kumar’s capability as an actor, I have my doubts if he would have delivered on the raw emotional intensity that Anupam brings. As he says, ‘Since it was my first film, I put whatever frustrations, heartbreaks I had till the age of 27 into it. It was not necessarily a man who had lost his son in America. It was Anupam Kher using his emotional memory of having slept on the railway platform, using humiliation on the streets of Mumbai, going through tough times, and the thought at the back of my mind that if this film does not work, it’s over for me. So I used those emotional memories and incorporated them in B.V. Pradhan.’

He adds: ‘At the time of embarking on a role, I always ask the director, “What is the core of the character?” In fact, five minutes before my first shot for Saaransh, I had asked Bhatt sa’ab: “If you have to describe B.V. Pradhan in one word, what would it be?” He said, “Compassion.” It is telling how that describes the arc of the character as he moves from grief and despair and irritability to a more compassionate view of the world. Reminding one of the Rilke poems I begin the essay with and its essence:

You be the master: make yourself fierce, break in:

then your great transforming will happen to me,

and my great grief cry will happen to you.

As Elaine Mansfield says in her analysis of the poem: ‘The last two lines said to me, “Divine being, transform me and allow my great grief cry to transform something larger than myself.”’ Pradhan, and with him we the viewers – such is the power of Anupam’s performance – are truly transformed over the course of the narrative.

However, it is also true that in the hosannas that have come Anupam Kher’s way, one tends to somewhat overlook the other brilliant performances in the film. First, Nilu Phule, in what is a villain comparable to Anna in Ardh Satya. So matter-of-fact and believable is the actor as the thuggish politician that every time he comes on screen, a cold fear grips the heart. His couple of interactions with Pradhan lend the film its dramatic highs in sequences that are remarkably understated.

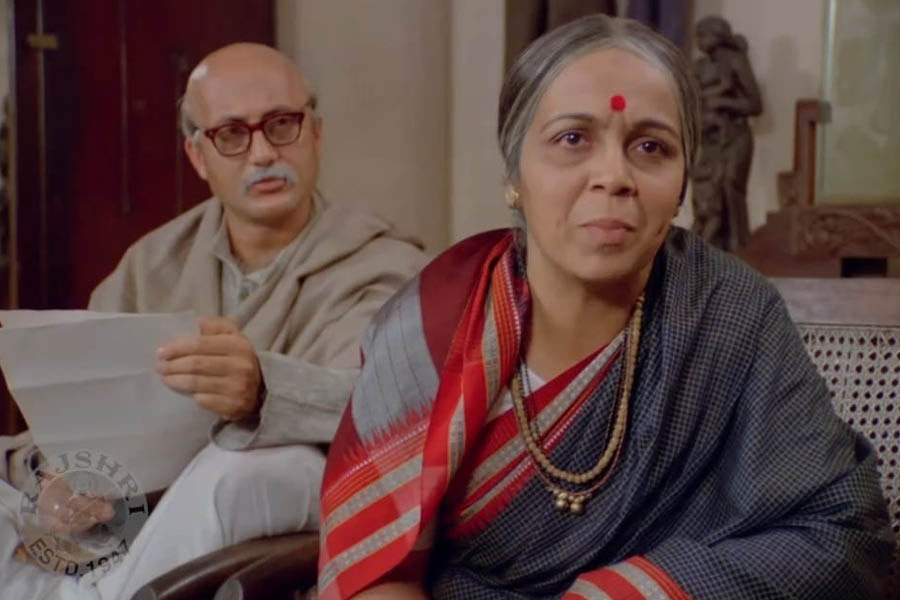

The other great act in the film belongs to Rohini Hattangadi. A lot has been written about Anupam being 27 at the time. We tend to forget that Rohini was all of 29! Fresh from the triumph of playing Kasturba in Gandhi, Rohini had the role of a lifetime in Saaransh. She is as good as Anupam, if not better.

The way she holds on to the belief offered by the god man in the initial stages, the belief that her son will be born again in her house – a way of denying herself the trauma of dealing with the truth. The mix of desperate hope and fear in her eyes, the calmness on her face born out of faith belied by her fragile body language. And if Anupam Kher has two of Hindi cinema’s most memorable moments in the sequences involving his interaction with the customs officer and the minister (who turns out to be his erstwhile student), Rohini has the film’s most emotionally shattering sequence.

As a viewer, one has just about recovered from the tribulations of the couple with the minister taking care of Gajanan Chitre and his goons, but Mahesh Bhatt isn’t done yet. He isn’t letting us go with what is at best a pyrrhic victory for the film’s protagonist. In the film’s most heart-wrenching moment, as Pradhan asks Vilas and Sujata to leave so that they are not tied down to Parvati’s misplaced faith and obsession, we have Rohini Hattangadi living the finest moments of her career, pleading, imploring with Vilas and Sujata not to leave, calling out to her dead son who she believes has found a new home in Sujata’s womb, and ending with calling her husband a monster for depriving her of her faith.

It takes almost all your willpower as a viewer not to tear your eyes away from the agony that the character is undergoing. It is to Rohini’s credit that she has you riveted in those three minutes of cinematic rendition of trauma. After which comes the heart-breaking realisation that her son will never return: ‘Ajay sachmuch mar gaya hai’ … that he won’t be reborn, that it’s just the two of them now with pictures hanging on the wall, and memories.

A note on the film’s music, which plays an important part in what the film leaves you with. If the background score – alternating between the baroque and the austere – stays true to the film’s essence, Vasant Deo’s lyrics and Ajit Varman’s compositions for ‘Andhiyara gahraya soonapan ghir aaya’ and ‘Dard ka doosra naam hai zindagi’ (Amit Kumar) do full justice to the pathos informing the narrative. The films of Mahesh Bhatt gave us some wonderful chartbusters in Aashiqui, Arth, Dil Hai Ke Manta Nahin, but seldom have songs been this expressive of the protagonists’ inner worlds as in Saaransh.

It’s easy to be overwhelmed by emotions in a film when one is young. I was blown away by Saaransh when I watched it as a 16-year-old. But when a film moves you to a blur in your eyes, when a scene as simple as an elderly couple who have lost everything caressing a bunch of wildflowers in a park – and the point that makes about the eternal nature of life – brings a lump to your throat in your 50s, it says something about the film. That the film and the experiences its protagonists have been through, the world it created 40 years ago, have survived the cynicism of your experiences. That what you have been through has not dimmed the purity of the film, its power, its essence.

(Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri is a film and music buff, editor, publisher, film critic and writer)