Seventy-two-year-old Dutch-Australian filmmaker Rolf de Heer travelled to Calcutta for the first time, this week, with his 2022 film The Survival of Kindness. The film, featuring a non-actor protagonist — a refugee from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, now settled in Australia — is being screened at the ongoing 29th Kolkata International Film Festival (KIFF). Heer’s film set in the backdrop of a post-apocalyptic world is an engaging narrative on the ideas of freedom and captivity and is also an allegory on racism. On the sidelines of the screening, Heer spoke to t2oS about the film and more.

The lead actors of your films are always unconventional, be it a mute child or a person with cerebral palsy, and in The Survival of Kindness, a person who has never been to a cinema before. Is the choice deliberate?

If I choose a child, I know that they cannot be an experienced actor because I can’t pay. In this case, it is a Black woman. There are many Black women who are experienced actors but the way we were making the film, the inexperienced actor worked best. If someone hasn’t acted before, when I meet the person, I start to think about what lies behind their eyes. Mwajemi (Hussein, the protagonist of the film) in The Survival of Kindness was a Congolese refugee who had many experiences as a child, and as an adult, those were profound. She had a depth of lived experiences. So, I thought maybe if we can trust each other then it can happen and the role was such. She did it and she did it incredibly well. It was her first film and she was terrific.

Your protagonist in The Survival of Kindness is named as Black Woman and even your other characters have no names. Why is it so?

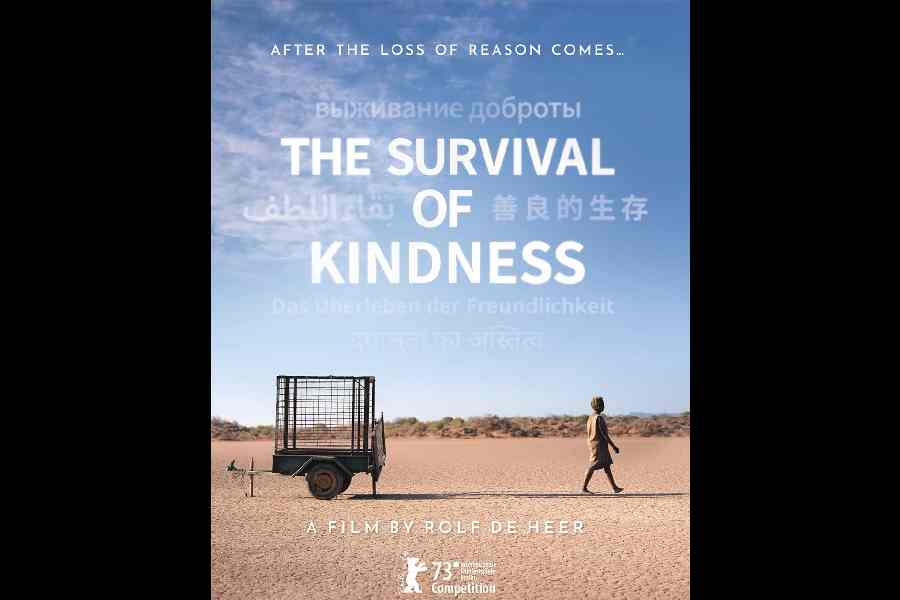

The poster (above) and protagonist (above right) of Rolf de Heer’s film The Survival of Kindness

Because the story is not specifically set in any country or any time. It is more universal. It is about all of us. If it was named then it would allow people to escape thinking this is her story and not mine.

The haunting image that the film begins with and recurs in the film is of a Black woman locked in a cage and stranded in a desert…could you elaborate on the image?

The first image that came to me was of a Black man. It was Peter Djigirr, who is a close friend and I worked with him a number of times also. It was him in a cage on a trailer left alone. I don’t know where the image came from and I don’t know why but once it came into my head it wouldn’t go out of my head. So I started working with it. He was unable to do the film at that time, so we had to look for another protagonist.

The film unfolds in a post-apocalyptic world and oscillates between the ideas of freedom and captivity. What inspired you to tell a story on the post-apocalyptic dystopia and how do you look at freedom?

Nothing in particular but it is how this story could best be told. I didn’t have anything particular for a post-apocalyptic backdrop. Except when I am doing it (telling a story with this backdrop), I want to do it well.

Freedom is a strange thing. We think it is a certain thing but it is not a certain thing. I remember, a long time ago in communist China, it was completely communist and people were saying it was a terrible place that had no freedom but somebody from China said I feel safe to walk home at night and that’s a freedom I don’t have in Australia and it is true. So, freedom is different to each of us.

With this film, you returned to the big screen after a decade… what took you so long to be back at the theatres?

After Charlie’s Country was made, I spent two years promoting the film around the world. It is just how it happened. And then I spent three years doing something I was really passionate about and only after that I could do a film again and in between there was the Covid pandemic too.

Humour plays a very important role in your films. Even in all the asperity of a film like The Survival of Kindness, the tinge of humour in the narrative was quite surprising. How do you look at humour?

It is important in any film. It is important for allowing an audience to breathe and I think only laughter can do that. I remember, there was a film called Ten: Murder Island. That subject matter started off very seriously but they suddenly make a joke and somebody says, ‘Stop, someone is farting too much’... it is a release. The indigenous people laugh a lot. So, we shouldn’t take it all too seriously. The audience has to have some good entertainment.

What are the issues in the indigenous community in Australia that need attention at present?

You name it and the issue is there. But the biggest issue is White people thinking that they are better than the Aboriginal people.

Producing films on indigenous people has always been challenging. Did your low-budget style of making a film make the process easier?

Big-budget films are very unpleasant to me. People get very angsty about money. You are forced to work longer hours and other stuff. For me, making one film is so difficult. If filmmaking becomes a job for me then I give up on it because as a job it becomes hard but as a passion it is easy. In America, they wanted me to do a remake of one of my films. I told them: ‘You are welcome to do it yourself but I am not doing it even if you give me five million rupees.’