Anti-racism protests are raging across the world, triggered by the street-side killing of George Floyd, an African-American, by policemen in Minneapolis in the US. A protest wave hashtagged BlackLivesMatter has resulted in statues of Confederate leaders all over the US being removed, destroyed or vandalised. In Britain, statues of slave traders and colonialists have been brought down. In Belgium, protesters burnt the statue of colonialist emperor King Leopold II who lorded over the deaths of millions of Africans at the turn of the 20th century. Statue vandalism in times of regime change or political tumult is not new, but such seminal iconoclasm in social protests is probably a first.

Vidyasagar’s statue in College Square, decapitated by Naxalites Tapan Das

Calcutta too witnessed removal of statues 50 years ago, at the time of the Naxalite movement. The targets were figures of bourgeoise political leaders and 19th century social reformers. “Busts of Vidyasagar and Acharya Prafulla Chandra Ray at College Square were brought down. Asutosh Mukherjee’s bust at Calcutta University was also broken by Naxalites,” says Sandip Bandyopadhyay, a researcher and historian. Among the others that were targetted were Gandhi, Tagore, Rammohun Roy and Vivekananda. In fact, Naxal leader Charu Mazumdar justified it all saying that the statues belonged to “intellectuals of bourgeois democratic revolution” who diverted common people from the anti-British freedom struggle.

Says Bandyopadhyay, “They didn’t realise that Rammohun and Vidyasagar were no less revolutionaries who fought against age-old superstitions, bigotry and Hindu hegemony. Neither did they explore how Asutosh struggled for autonomy in higher education against the colonial masters.” Years later, Naxalite leader Ashim Chatterjee admitted at a public meeting, “We failed to recognise a revolutionary in Vidyasagar. He was the nerve centre of Indian renaissance, an indigenous struggle.”

Before India’s Independence, 37 statues of Raj icons had been installed in Calcutta — around the Maidan area, Red Road and the banks of the Hooghly. When the Victoria Memorial was built in 1906, a dozen were placed on its premises. The Naxalites did not touch any of these.

But by the early 1970s, the United Front (UF) government had already started removing these statues out of public sight. According to Bandyopadhyay, the initiative was led by Subodh Banerjee, SUCI leader and PWD minister in the UF government. The minister, however, appreciated the artistic value of these sculptures; he didn’t believe in their destruction. The then governor of Bengal, Dharma Vira, ordered that the statues be installed on the Flagstaff House premises in Barrackpore, with restricted public access.

Of the 37 statues, 13 were rehabilitated in Flagstaff House, the erstwhile address of the viceroy’s private secretary, and currently the local retreat of the Bengal governor.

Statues of nationalist leaders came up instead. For instance, at the northern gate of the Victoria Memorial, freedom fighter and philosopher Aurobindo replaced the racist viceroy, Lord Curzon. The workmanship on the new statues, however, was no match to the works they had replaced.

Curzon’s statue — crafted by British sculptor Hamo Thornycroft in 1911 — has a proud forehead, an imperious nose and a pointed gaze. In its place, Aurobindo’s statue looks emaciated and forlorn. And ironically too, Curzon had been the driving force behind the protection of India’s architectural heritage and was instrumental in passing the Ancient Monuments Preservation Act of 1904.

Curzon’s statue had been part of a memorial. It was surrounded by smaller statues or statuettes representing commerce, agriculture and famine relief — supposedly significant achievements of the former viceroy. While the main statue was banished to Flagstaff House, the statuettes remain. Stripped of their original context though, they remain reduced in every sense.

In Barrackpore, Flagstaff House is referred to by locals as Latbagan or the lord’s garden. Amidst its verdant groves stand the statues. Viceroys Lord Curzon, John Lawrence, Thomas Baring and the Earl of Northbrook; Edwin Samuel Montagu of Montagu-Chelmsford reforms; and the Earl of Ronaldshay who was the governor-general of Bengal — all are carved in bronze and transplanted from around the Calcutta High Court area. Some of the others, on horseback, are the earls of Mayo and Minto. Captain of the Royal Navy, William Peel, who died shortly after the 1857 uprising, is the lone marble figure.

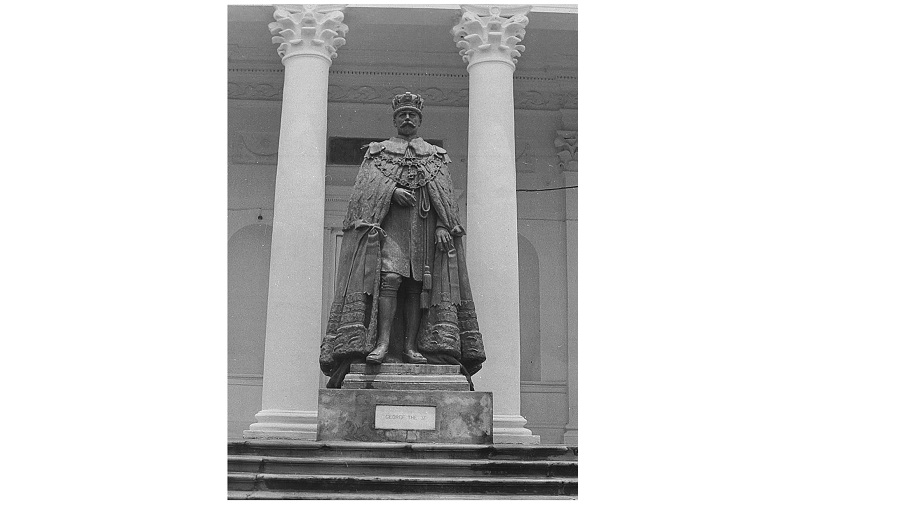

King George V in Latbagan, Barrackpore Ashoke Majumdar

In front of the Hall of Fame at Flagstaff House is a statue of King George V. It was erected in 1939 with much fanfare and once adorned the crossing of King’s Way (now known as Gostha Paul Sarani) and Strand Road. In Mrinal Sen’s film Interview, there is a scene in which this statue is shown being hauled away by a PWD crane — a reminder of the end of British imperialism in India.

Remarkably, little damage has been done to imperial statues in India, says historian Rosie Llewellyn-Jones in an email interview from London, UK. She has visited Flagstaff House several times. She says, “One statue of Lord Wellesley was beheaded [in Bombay in 1969] and a couple of Queen Victorias lost their hands, but apart from that these, reminders of foreign rule have been well treated. It was sensible to move some of them to Barrackpore, although Queen Victoria remains serene outside her memorial hall. Calcuttans accepted colonial statues as part of a shared heritage.”

In 2006, the then mayor of Calcutta, Bikash Bhattacharya, had revealed plans to rehabilitate the banished statues from Barrackpore to Citizen’s Park adjacent to Victoria Memorial. British architectural historian Philip Davies was consulted for the project. Davies tells The Telegraph via email from London, “I discussed the reinstatement of selected statues on their plinths with the former mayor about 10 years ago, but it came to nothing.”

Llewellyn-Jones deplores “the sudden trend of demolishing the past”; she calls it “retro-liberalism”. For Davies, the statues are important works of art by leading sculptors of the time.

Davies, who also chairs the Commonwealth Heritage Forum in Britain, says of the recent events in England, “If campaigners seeking to remove those statutes relating to Britain’s colonial past want a genuine debate around shared heritage, then the answer is not cultural iconoclasm but to retain them in the public domain as focal points to stimulate the very dialogue they crave.”

Heads in Tailspin

Those whose statues have been recently targeted

Christopher Columbus

Hailed as the discoverer of the New World and considered by many to have spurred genocide against indigenous Americans

Minnesota to Boston, Miami to Richmond, Virginia in the US

Jefferson Davis

President of the pro-slavery Confederate States of America during the 1861-1865 Civil War

Richmond, Virginia, US

Albert Pike

Confederate General during the Civil War

Washington DC, US

Robert E. Lee

Confederate General during the Civil War

Richmond, Virginia, US

George Washington

First US president and general of the country’s Revolutionary War forces during the American War of Independence New York, US

(Since Floyd’s killing in May, 23 statues of Confederates have reportedly been removed. There are over 700 Confederate monuments and statues across the US. Over the years, 80 statues have been taken down)

Edward Colston

17th century slave trader in the West Indies

Bristol city harbour in the UK

Robert Miligan

Scottish merchant and slave trader

East London, UK

Robert Baden-Powell

British Army officer in the Southern African War (1899-1902)

Dorset, UK

Cecil Rhodes

Trader and imperialist in South Africa

University of Oxford, UK

Leopold II

Longest reigning monarch notorious for atrocities and killings in Congo

Antwerp, Mons, Leuven, Ghent in Belgium

John F. Charles Hamilton

Colonial military commander; crushed Maori tribals

Hamilton in New Zealand