Book: Last Call At The Hotel Imperial: The Reporters Who Took On A World At War

Author: Deborah Cohen

Publisher: Random House

Price: $30

Deborah Cohen’s book is likely to overwhelm the general reader with a subject and a story that’s distinctly unusual. At its most basic, it’s an ensemble biography of young American journalists who stepped out of their provincial homes in the heart of America and stumbled into the turbulent world of inter-war Europe as reporters on a mission to tell the world how the post-Great War order was faring in the face of the dramatic rise of ‘strong men’ politics. The prologue sets out the tenor of the book which reads less like a staid academic monograph and more like a novel with an extraordinary cast of characters, multiple plot lines, dramatic action, romance, intrigue and daring sexual intimacies and encounters. The academic temper of the book however shines through in Cohen’s deft embedding of these intimate personal stories within the broader history of inter-war geopolitics, the emerging forms of media ownership and enterprise in the United States of America, the debates on the journalistic form, the commitment to the ethic of objectivity, and the elusive search for truth in a world driven by power, propaganda and pelf.

Cohen begins with the personal stories of each of her protagonists with brief biographical sketches of their early lives, education, and aspirations and then veers into the larger context of the American media and their global interests in the inter-War years. What was the media’s interest in post-War Europe? What were the modalities through which it sought a firmer foothold there? For regular dispatches from foreign countries, the American media depended on wire services which, in turn, relied on the local press. But as Cohen observes, this arrangement changed quite radically after the Great War. Now Americans came to believe that they required their own insights into Europe. The War had taught them their lessons. As Cohen put it, “Never again would the Europeans, particularly the Brits, trick naïve Yankees into a costly Continental entanglement.” This was a widely-shared sentiment among several leading newspapers that devoted renewed resources to set up a robust foreign news service in Europe. Among those that made a distinctive European presence were the Chicago Daily News, The New York Times, New York Herald Tribune, Chicago Tribune, Christian Science Monitor and The Philadelphia Evening Ledger.

It is against this backdrop that Cohen weaves together a dense account of five intrepid reporters who risked their lives, fortunes and reputations to bring that ‘story’ of Europe that resonated with a readership not only in New York or LA but also to those far removed from elite cosmopolitan circuits. But in the course of their sojourns in Paris, Moscow and Vienna, they also realised how much the fate of Europe was tied to the politics that unfolded in the larger reaches of European empires. From their European posts, therefore, they soon sought out ‘beats’ in Shanghai, Delhi or Addis Ababa.

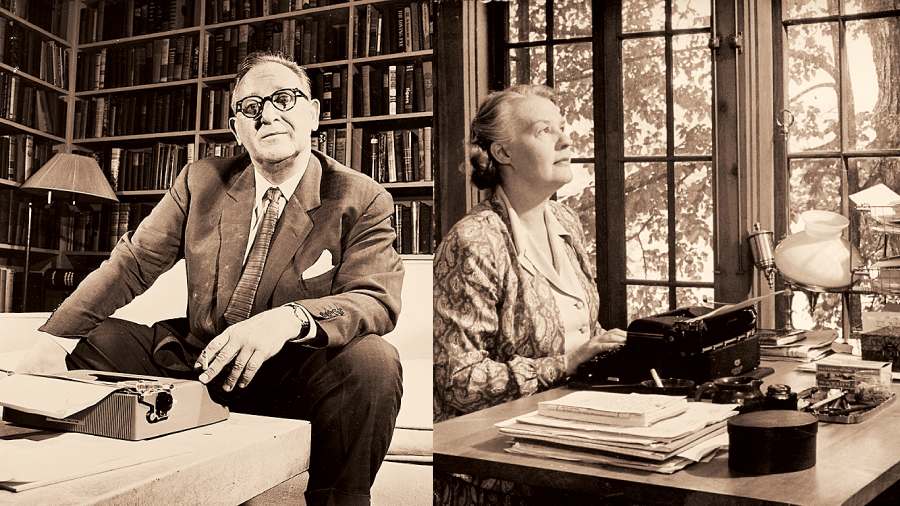

The five young correspondents were John and Frances Gunther, Dorothy Thompson, H.R. Knickerbocker and James Sheean. H.R. Knickerbocker, also known as Knick, won the Pulitzer for his reporting on Stalin’s Russia; Jimmy Sheean, won the first National Book Award for biography; Dorothy Thompson was the first woman to head a foreign news bureau in Berlin and Gunther’s wife, Frances, developed a keen nose for the tenor of anti-colonial nationalist politics as it took shape in India. Although her husband, John, acquired fame for his remarkable insights into the turbulent politics of Europe and Asia, it was Frances who was able to delve deeper into the intimate spaces of Indian politics, enjoying enduring friendships with its younger leaders, most notably Jawaharlal Nehru. Sheean, too, felt the pulse of Indian politics in the 1930s. He had predicted — quite uncannily — that Gandhi could be killed by a fanatical Hindu.

For the young reporters, most of whom came from provincial America, the political landscape of inter-war Europe and Asia was overwhelming. They saw the Wilsonian system created at Versailles take an awkward shape as newborn republics struggled to find political stability, they witnessed the glorious and calamitous faces of the Soviet experiment, and they watched in horror how the ideologies of fascism, communism and democracy collided and churned amid widespread economic distress. They tried to make sense of the rise of the new dictators all across central and western Europe as a peculiar manifestation of the psychological crisis of the times. As Cohen notes, Freud became part of their “mental furniture”, giving them insight and vocabulary to make sense of the complex interplay of the individual and the collective unconscious in the making of nations and their destinies.

Cohen’s story is of a remarkable group of young Americans who followed the ‘Lost Generation’. Unlike their predecessors though, they never left Europe when it began to crumble, but stayed back to tell the story of its predicament in the face of unrelenting chaos and human suffering.