Book name: Delhi, Agra, Fatehpur Sikri: Monuments, Cities and Connected Histories

Author: Shashank Shekhar Sinha

Publisher: Macmillan

Price: Rs 599

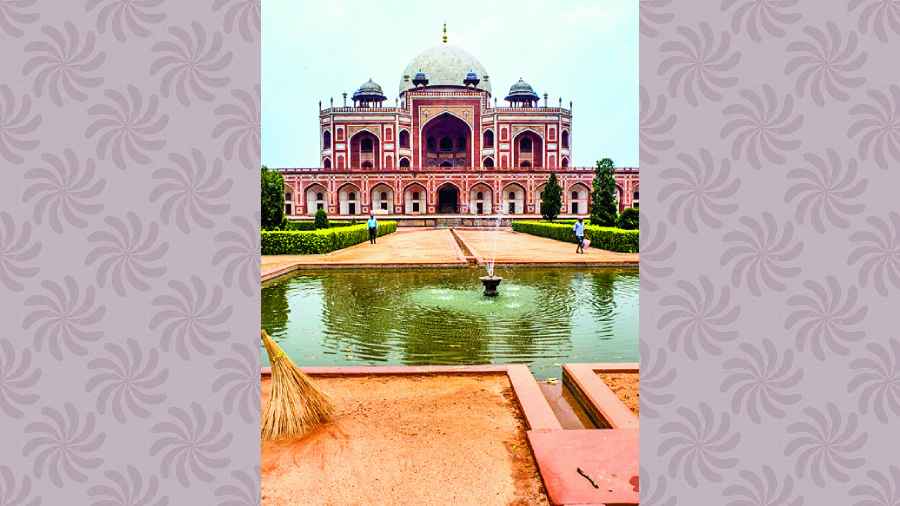

At a time when the Central Vista project casts its looming shadow over Delhi, the Qutub Minar drops out of a UGC list of 100 must-see destinations for students under the ‘Ek Bharat Shreshtha Bharat’ project — just as the Taj Mahal was cold shouldered by UP tourism’s list a few years ago — and the weaning of our national nomenclatures away from Mughal appellations continues merrily with Mughal Sarai and Allahabad, Shashank Shekhar Sinha has written a book that reclaims our Indo-Islamic past by presenting a lucid and highly readable survey that serves a three-fold function: as a guidebook with academic heft, a corrective to many misconceptions and myths, and a summation of interesting academic and ‘public history’ questions surrounding six of the most iconic heritage monuments in India. These are the Qutub, Humayun’s Tomb, and Red Fort in Delhi, Agra Fort, the Taj, and Fatehpur Sikri in or near Agra — connected not only by their shared presence on the Unesco World Heritage List but also by the ties of history, heritage, architecture, aesthetics, public culture, and, of course, politics.

The book’s raison d’être is laid out clearly in the ‘Author’s Note’ at the end — “to address the lacuna between the knowledge produced in academic settings and its eventual consumption at ground level”, with a view to making visits to these monuments enjoyable and meaningful. Sinha delivers not only with grace and empathy but also with a clarity of vision and organization, evidenced most clearly in a preliminary section that lays out a roadmap about how to navigate the book and glean the most from the chapters following a uniform pattern on all the monuments — origins and evolution, architectural details, ideas as well as idiosyncrasies of the rulers who built them, their afterlives — often fraught with debates and controversies — and the rich tapestry of anecdotes and folklore surrounding them.

The many nuggets of often counter-intuitive historical facts add micronutrients to a book that compellingly distils the voluminous academic scholarship on these monumental signposts of medieval and early modern India. It is instructive to know that the familiar touristy pit-stops in Fatehpur Sikri — like the structures going by Todar Mal’s, Birbal’s or Jodha Bai’s palaces — are misnomers, possibly fed by a canny guide to unsuspecting British officers. It is also curious to note that the English traveller, Ralph Fitch, visiting Agra around 1585, conceded that “Agra and Fatehpore... are two very great cities, either of them much greater than London and very populous.” And it’s sobering to learn that in the aftermath of 1857, stripped of all royal privileges and entitlements, the descendants of one of history’s greatest ‘Gunpowder Empires’ subsisted by growing vegetables in the magnificent ‘Paradise’ gardens of Humayun’s tomb.

Sinha has given us a tour de force, which is essential reading for those who plan to visit these iconic monuments as well as for those who would like to have a glance at a textured, multilayered history of medieval India through the vantage windows offered by six sites. For all the ease of reading however, one can’t escape the thought that the technicalities of specialized elements of Indo-Islamic architecture — ashlar, entresol, trabeate brackets, chamfered corner, barbican, finials, spandrels — could have been separately explained in a glossary. One also feels a little wistful about the one missing piece from the septet — the Lahore Fort, with its exquisite and effervescent picture wall, whose inclusion in the book could have foregrounded the transnational resonance of Mughal monumental architecture. Of course, that is in Pakistan and thus probably off-limits, but it is a testimony to the strength of Sinha’s writing that he, nonetheless, stokes this yearning. Another book in another time, perhaps?