Book: Who is black and why? A hidden chapter from the eighteenth-century invention of race

Editor: Henri Louis Gates, Jr. and Andrew S. Curran

Publisher: Harvard

Price: $29.95

At one level, this edited collection is a contribution meant for eighteenth-century scholars and specialists interested in histories of science, race and medicine. It puts together nineteen translated essays (eleven from French and eight from Latin), which had reached Bordeaux’s Royal Academy of Sciences in response to the essay competitions organised by it in 1741 and 1772, respectively. The topic for the first prize contest, which elicited sixteen essays, was “What is the physical cause of the Negro’s color, the quality of [the Negro’s] hair, and the degeneration of both [Negro hair and skin])?” The theme for the second essay competition, which received only three entries, was “What are the best ways of preserving Negroes from the diseases that afflict them during the crossing to the New World?” However, the book is much more than a collection of translated essays as the editors’ introductory essay evocatively delineates the context wherein an intricately complex and hidden history of race is intertwined with that of scientific methods and discoveries. It offers a peek into processes through which “Enlightenment-era naturalists progressively transformed the alleged cognitive and physical differences existing among the world’s peoples into normalized categories.” These taxonomical schemes facilitated the development of an insidious relationship between science and race whose ultimate function was to position white Europeans at the pinnacle of a fixed racial hierarchy.

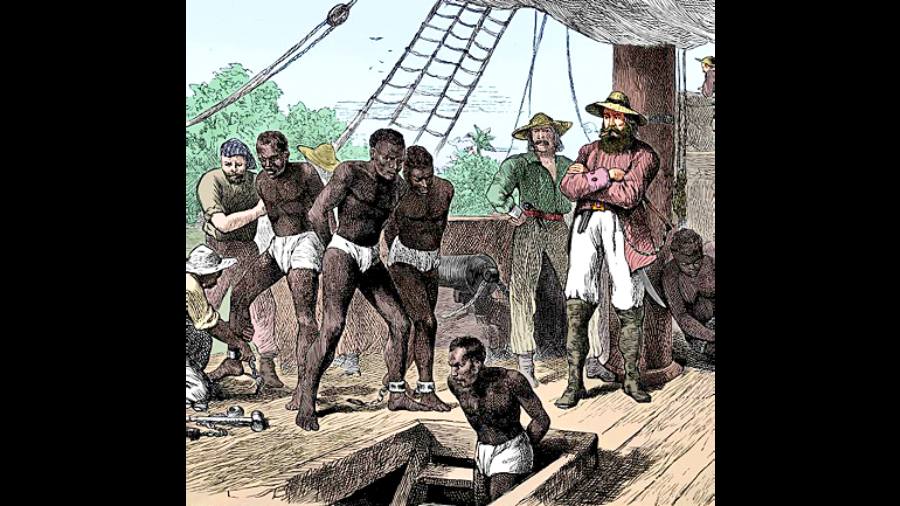

As the editors justifiably argue, race was never an innocuous taxonomical concern for the scientists who would increasingly claim the right to provide compelling, anatomy-based explanations for humankind’s many varieties. Their scientific claims were rather complicit in vindicating the ongoing dehumanisation of people of colour in the Americas and elsewhere. After all, Westerners’ interest in the origins of blackness did not occur in an intellectual vacuum. Rather, their quest for knowledge about the African variety’s distinctive physical traits was deeply implicated in the ever-growing dependence of European economies on African slave labour throughout the New World. Revealingly, the themes of the two essay-prize contests purport to hide a life of brutal enslavement in plantations on the other side of the Atlantic and trans-Atlantic slave trade. The second theme acknowledges the fact of loss of lives in transit, it obscures the city’s and France’s relations to New World slavery. Apparently, the second theme underlines the need for ‘humane’ transit for black bodies without explicitly accepting the institution of human bondage and its intimate linkages with blackness. It simply bypasses the metonymic functions of blackness whereas “the color black was a metonym for Africans, [and] Black Africans themselves were undoubtedly a metonym for slavery and the trans-Atlantic slave trade.”

At another level, this volume sheds light on the blind spots of Enlightenment-era thinking where the rhetoric of progress and humanitarianism co-existed with human bondage. The scientifically-based quest to improve human conditions seemed perfectly compatible with the economic imperatives of African chattel slavery. In this sense, the book is about the limits of Enlightenment universalism as well. As the editors put it pithily, “in many cases the benevolent ideology of Enlightenment simply did not apply to non-Europeans, especially Africans.” Otherwise, Immanuel Kant, a champion of internationalism and cosmopolitanism, would not have carried on with his life-long vilification of the Negro whom he considered to be less than fully human. Likewise, the philosopher, David Hume, unhesitatingly described Africans as naturally inferior and totally unsuitable for ‘arts’ and ‘sciences’. Evidently, dark skin was seldom a matter of pigmentation. Instead, it came to function as an a priori sign of stupidity, lack of reason, and an inferior moral character. Even Montesquieu, who played a key role in underscoring the fundamental evil of slavery on the basis of natural law, found servitude to be a natural, climate-induced condition for people living in the Torrid Zone in the same manner as people living close to the equator were pleasure-driven, unthinking, and lacking in curiosity and noble sentiments. At the same time, the Enlightenment philosophes, such as Voltaire, Helvétius and Diderot, extended the abolitionist line of thinking.

Yet, as the murder of George Floyd, a 46-yearold black man, by a white police officer in the US city of Minneapolis in May 2020 testifies, even today being black signifies lesser consideration in terms of human dignity and worth. Viewed thus, this book is a well-researched entry into the history of race as an idea and an ideology and its continued function as a systemic source of discrimination.