After winning a landslide victory in the 1977 assembly elections, the Sheikh continued to play the politics of manipulating popular political sentiment. To be fair to Abdullah, he never ceased to nurse the dream of an “independent” Kashmir, but he was caught between his two mutually opposing ambitions — the yearning for independence, and the quest for power which destroyed him as well as Kashmir. In the early 1950s, Josef Korbel, who was intimately associated with the politics of Kashmir, made an objective assessment of Abdullah — a characterisation that remained true of him till his death. Korbel said, “The story of Sheikh Abdullah is a sad and sorry one. It is a story of a patriot, once passionately devoted to his people’s welfare, but one whose patriotism was too shallow to reject the temptations of power.”

Immediately after assuming power in 1975, Sheikh Abdullah constituted a four-member committee headed by Mirza Afzal Beg to draft a proposal for the restoration of autonomy to Kashmir. As Beg knew that there was no scope for restoring the autonomous position of Kashmir, he avoided working on the proposal. After his dismissal from the cabinet, Sheikh Abdullah appointed two committees to submit separate reports on the issue. One was headed by D.D. Thakur and the other by G.M. Shah. Thakur in his report opined that this demand would only impair relations with the centre. The Sheikh observed silence thereafter. It is also important to mention that in 1975-6, the National Conference published a pamphlet, Why Autonomy to J&K State? A delegation of the National Conference, which was invited to attend the All India Congress Committee meeting at Chandigarh, attempted to distribute the pamphlet among the members. Indira Gandhi took serious note of this and had the move stopped, and did not provide Sheikh Abdullah the opportunity to address the meeting. The Sheikh felt so humiliated that he emotionally asked his cabinet members to be ready to resign.

Sheikh Abdullah continued speaking from his heart, but could do nothing practically. On the day of the National Conference victory in the 1977 elections, he gave a statement to Voice of America pledging to work for the restoration of autonomy. Governor B.K. Nehru, with whom Sheikh frequently used to spend his leisure time discussing freely and frankly the affairs of J&K, besides “the whole universe”, writes:

“…it became clear from our conversations from time to time as well as from the difficulties he was creating in accepting wholly the Constitutional demands of the Centre that his objective was… the eventual creation of a separate independent state consisting of at least the Valley together with such Muslim areas of Jammu division as could be tagged on to it.”

Ahmad, principal secretary to Abdullah, corroborates Nehru’s account with thick detail. He observes that the ambition to carve an independent position for Kashmir stayed with the Sheikh permanently, till his last breath:

“He was till his end toying with and working for the idea of a Greater Kashmir comprising the valley including Kargil District, Muslim majority areas of Doda, Bhaderwah and Kishtwar and parts of Udhampur District namely Ramban, Batote, Gool Gulab Barh, Banihal, and Poonch and Rajouri Districts of Jammu province with minor adjustments for reasons of topography. It was with this objective in view that a special Division of R&B Department was created reviving and converting the old Mughal Road linking Rajouri District with Shopian of Pulwama District in the Valley into a permanent and all weather road. Similarly, work on construction of Daksum (in district Anantnag) Kishtwar road was started in right earnest. This road was to provide a link with Kishtwar, Doda and Bhaderwah. The Central Government was also asked to upgrade, improve, and realign the Batote-Doda road, which was subject to frequent landslides and resultant closure of the road for days on end.”

Meanwhile, Abdullah, at least, demonstrated that he was a chief minister with a difference. He was reticent in accepting Indian Administrative Service officers from the centre to form a part of the state cadre; nor did he permit the chief justice of the high court who was a Kashmiri to be transferred. Abdullah also resurrected the Resettlement Bill. Besides other things, the bill signalled to the people a move towards the reunification of people divided by the Line of Control — and the possibility of returning to the time when the state was undivided. Writing about the challenges which the authority of the centre faced on Kashmir when he took over as governor, B.K. Nehru says:

“The challenge to the authority of the Centre which the Sheikh was making when I took over charge were three. The first was his refusal to permit the Centre to send IAS officers to form part of the state cadre as was custom in every other state of the Union. The second challenge consisted in the refusal of the Sheikh to permit the transfer of the acting Chief Justice of the state and his replacement by a nominee of the centre from outside the state as was, and is, the practice in all the other states of the Union. The third problem was much more serious. Some considerable time earlier a bill had been introduced in the Assembly by a private member, entitled the Resettlement Bill. It provided that residents of the state who has left it between 1947 and 1954 to go to Pakistan could be allowed to come back and resume all their rights as Indian citizens.”

Indeed, in the contemporary political history of Kashmir, Abdullah is the last example of the head of government trying to assert his authority. He differed, though politely, with the governor who refused to sign the Resettlement Bill. What transpired between Abdullah and the governor is interesting to hear from the then governor himself, as it alludes to an assertive role of the chief minister as the representative of the people vis-à-vis the head of the state as representative of the central government:

“I warned Sheikh that I would not sign the bill as it was so clearly unconstitutional. His argument was that it was none of my business whether the bill was constitutional or not; that was the business of the Supreme Court. I should sign the bill when it was passed, if anybody had any objection to its constitutionality they could go to court.”

Congress-National Conference Confrontation

No sooner did the Sheikh take up the reigns of government than the Accord was converted into discord, following the confrontation between Sheikh and the Congress party over the politics of hegemony, which continued throughout the Congress-backed rule of Abdullah and after. Leaving the details to the following section, it suffices to say here that the people construed this embittered relation between Congress and the National Conference as a fight between New Delhi and Srinagar to dominate Kashmir in a struggle among unequals. Abdullah issued a press statement saying, “since the Congress had withdrawn its support to me, therefore, the Accord between me and Mrs Gandhi should be treated as cancelled.”

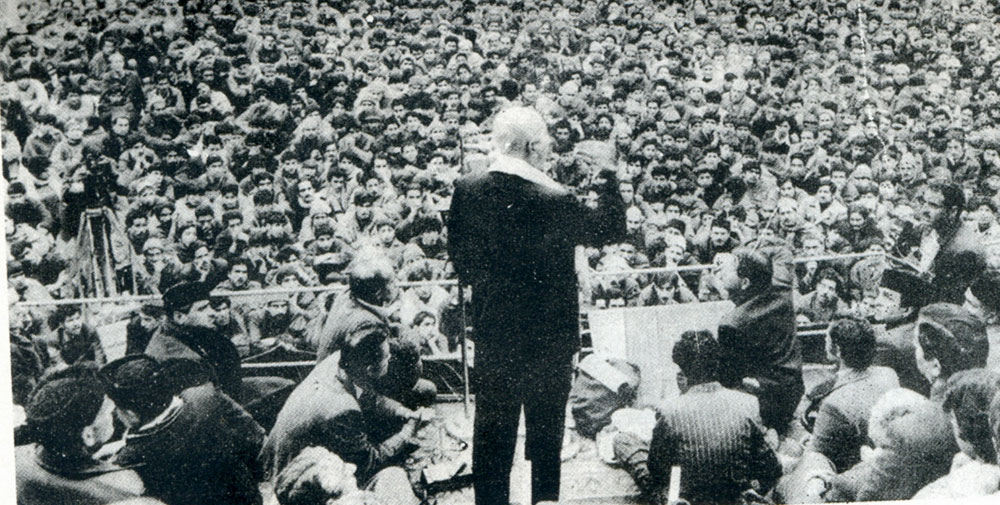

All factors mentioned in the preceding discussion help us fathom the sustained popularity of the Sheikh till his death. Soon after his demise, the “rebels” who had “withdrawn” during the hustle and bustle of the Abdullah government, to conceive of a new strategy to actualise the will of the people left half-done by the mass leader, returned to revive the suspended course of history, which found considerable favour with the young generation, more than ever, in the changed circumstances.

Reproduced with permission from What Happened to Governance in Kashmir? by Aijaz Ashraf Wani; Published by Oxford University Press