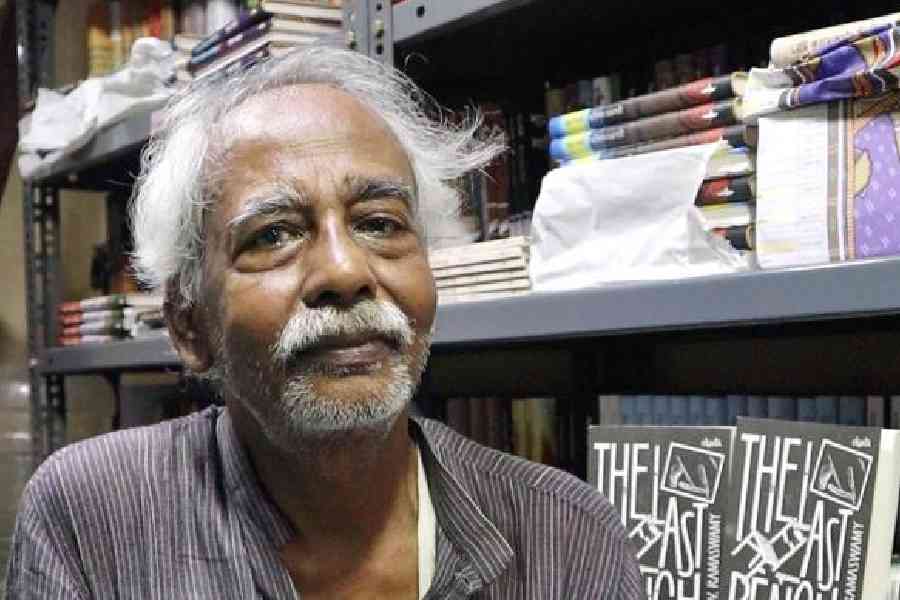

He is as unassuming as one can be. Wearing a faded blue kurta, with creases of the day’s work smeared in its natural folds, he is engrossed in his world of books, surrounded by voices like his at his publishing house Gangchil, in Barnaparichay Market complex. One can easily miss him in the labyrinth of shops at Calcutta’s book hub. Old age has embraced him. He is no longer the little boy roaming about in his village, Magura, in the then East Pakistan and now Bangladesh, playing with his friend Dulal, or most of the time alone, helping his baba in getting customers to his barber shop, finding solace in his mother’s arms, and being the last-bencher and learning the realities of being poor, and particularly a Dalit, in India, as described without any inhibitions in his memoir The Last Bench, translated to English by V. Ramaswamy, that made a round of the city recently. The book was the winner of the English Pen Presents Award for Translation 2022.

Adhir Biswas has come a long way. Having migrated to Calcutta in 1967 at the age of 12 and struggling to make a living for himself, he has written 22 volumes of fiction and non-fiction, including two sets of refugee memoirs, and two childhood memoirs. His works have been recognised and he has won multiple awards. His memoir, Allahr Jomite Paa, won the West Bengal Bangla Academy’s Suprabha Majumdar Memorial Prize in 2014. His four-volume collection of stories, novellas and novels for young readers, Udojahaj, won the Vidyasagar Prize in 2017.

What prompted him to start writing? “After coming to Calcutta, when I started studying in college, I used to hawk in trains to sustain myself. Once, I met someone from my village in East Pakistan, who left that village some years after I had left. He was a brilliant student studying in medical college and was associated with a magazine or periodical. When he realised that I was in need of money, he asked me if I could write. He told me I would get 20 to 30 rupees per article. That stuck in my head and I started writing as a means to make both ends meet,” began Biswas, as we started talking, with Ramaswamy for company. The latter has translated works of writers from West Bengal and Bangladesh like Manoranjan Byapari, Subimal Misra, Mashidul Alam, Swati Guha, Ismail Darbesh and others. Interjecting and mentioning an important point, Ramaswamy said: “So it was just a medium to earn. The question could have been,

can you shine shoes? You’ll get ₹5 per shoe. Any job that would give him more money, he would have said yes. So, it was incidental that it was writing.”

Incidental but instrumental in charting a course for him that would make him one of the most illustrious names in Dalit literature. With the guidance of his friends, what started as a means of living metamorphosed into something that he never expected in his life. He started writing for kids with the publishing house Doyel. And soon moved to writing for adults and sharing his stories with his memoirs.

Gangchil, his publishing house, was an organic extension of his work in the field of writing and publishing. Talking about his entrepreneurial side, he said: “I used to work as a proofreader, day and night. It was an experience for me. Soon it dawned on me that what if I could publish my work. If I lose my job, what will I do? It is these thoughts that gave birth to Gangchil. It started on a small scale, and I maintain the quality of the books. Since I was associated with publishing for many years, I was at the forefront of technology and had a very high-profile art department with highly paid artists. I imbibed that work aesthetics.”

Unfazed by his achievements, providing a platform to writers and poets from the marginalised communities, is now Biswas’s only goal in life.

His memoirs are raw, unfiltered, brave and written with utmost sincerity. Immensely descriptive and candid, Biswas doesn’t shy away from sharing anecdotes from his life that some readers might find distasteful. His prose brings out the vulnerability of the life he has lived, sharing with readers the dark reality which is also a part of India. The Last Bench, that talks of a specific period of Biswas’s time, is not graphic but hits hard with the innocent voice of a child wanting the bare minimum from life.

“Memory, healing, emotions… were raised,” reflects Biswas when asked about the feelings that writing a memoir about a childhood elicited. “It’s all inside me and it came out naturally through the flow of the pen. It had to come out,” stressed Biswas.

What would he say if he met Ratan (the name he gives to his character in the memoir) now in his village, ambling or taking jibes for being from a low caste? A wide smile flashed on his face and with a spark in his eyes, as if transported to his village, he said: “I would say, I know this is a bit rough, but keep going. People will recognise you, you will get through all these things.” Coming back from his reverie, looking straight into our eyes, he added: “I have only gained from my experiences. And those experiences are a treasure for me to write about now.”

Biswas, who is currently the publications editor of the Dalit Sahitya Academy in West Bengal, discussed the significance of representation in literature, particularly for marginalised communities.

Self-effacing was soon consumed by confidence and he emphasised: “The representation of the marginalised people in every sphere, be it politics, literature or in society, is a necessity. Only when our voices are heard and we have presence in all spheres that people will know, they will become aware and educated. Then only society will become a better place.”

Taking up from Biswas and talking about the challenge and reward of translating The Last Bench and his other works, Ramaswamy said: “His style of writing is very interesting. He is like an open book. He has shared everything about his life. It was very moving, touching, poignant. Sometimes I was in tears, overwhelmed by the tragedy of the poignancy of it.”

Ramaswamy, who has known Biswas for the last 10 years, added: “He uses words that are very native to him and I had to keep going back to it to decipher. I have learnt a lot. Also, he uses a cryptic method and at times I would wonder if is it a question or a statement. Sentences which might appear incomplete were complete if looked at from his style. I kept that cryptic style, retaining his flavour while translating.”

While Biswas wants to keep writing more about his experience in Calcutta, Ramaswamy wants to embolden those voices and expand their reach to a wider readership.