Picture Credit: Sasanka Mondal.

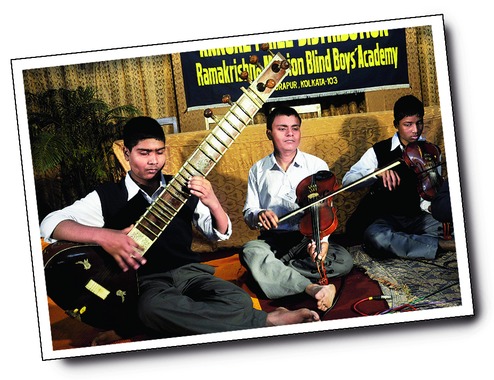

Asit Shil will be taking his Class X exams next year. He has his way with the sitar, has had his fair share of pranks, has even been suspended for a few days. And yet his life isn't exactly like most boys his age.

Asit is a student of Ramakrishna Mission Blind Boys' Academy (BBA) at Narendrapur in South 24-Parganas.

Of course, now, after the Government of India's recent decision to revise the 40-year-old definition of blindness, he will not be regarded as "blind" but as someone with "visual impairment". The government move is an attempt to bring the existing definition to something in line with the World Health Organization (WHO) specifications. Right now, a person unable to count fingers from a distance of six metres is categorised as "blind" in India, whereas the WHO's stipulation is three metres.

However well intentioned, it isn't yet clear how this redefinition will impact Asit. But there is something that will.

That would be the move to revise Bharati Braille (BB), the unified Braille script used to read and write Indian languages.

Braille is a tactile writing system used by the blind. Braille characters are small rectangular blocks or cells containing palpable bumps or raised dots. Their number and arrangement help distinguish one character from another. Since the Braille alphabets originated as transcription codes of printed writing systems, the mappings vary from language to language. The Braille scripts for the various Indian languages - 17 in all - draw on Bharati Braille.

Biswajit Ghosh, who is the principal of BBA and also blind, says: "Language is dynamic. Many new words and symbols have been introduced into Indian languages through the years. It is high time they were incorporated in our script too."

The six decades of non-action, therefore, was like a time warp in language terms. Something akin to reading in Old English while speaking in 21st century English. And yet, in 1949, India was instrumental in arranging for a discussion at Paris to frame a uniform Braille code. The advisory committee included Suniti Kumar Chatterjee, linguist and head of the department of Comparative Philology, Calcutta University. In fact, it was due to the efforts of people like Chatterjee that Bharati Braille was finalised in 1951.

In any case, in the absence of an updated script all this while, each language group had come up with its own set of codes and improvisations. Extremely confusing for a blind person who can and wants to read books in more than one language. The revision project led by the National Institute for the Empowerment of Persons with Visual Disabilities, Dehradun, assessed and assimilated most of them. It meant over five years of rigorous work by the executors, the Braille Council of India. "Groups were formed to identify gaps in the BB code. And the wheel was set rolling with 15 language representations," says Ghosh, one of the persons involved in the script updation. It all culminated at the National Conference on Revision of Bharati Braille in Guwahati on March 27.

Incidentally, the codes used for the transliteration of bold, italics, underline and tick in Bengali Braille - the script used for Bengali and Assamese - were accepted unanimously in Guwahati. Some other suggestions, such as the codes for "ph" and "f" sounds, have been left subject to field testing.

The next thing to do is spread awareness about the new unified script. A lot of schools for the blind are still unaware about these developments. And even if the smallest of sections do not get to benefit from this revisionary exercise, the whole purpose will come to naught.

Others will have to be brought around. Subhadip Mondal, who is a year junior to Asit and also a student of BBA, does not seem too excited to learn about these changes. He has an exam to prepare for, after all. He says, "When you look at a sentence or sum, you 'know' if it is a full-stop or decimal point. Not so with us. We have to memorise two sets of codes to figure out what is what." True, that. But his point? "Why burden us with that Physics chapter on light?"

Now, that needs a different kind of re-visioning.