The 1946 Calcutta Killings, a black chapter of history, has re-emerged from the mists to suddenly become a topic of discussion in poll-bound Bengal, courtesy under-the-radar fear-mongering by the saffron ecosystem over social media.

While the BJP’s campaigners and official accounts have not mentioned the 75-year-old communal conflagration, its supporters have been broaching the topic over WhatsApp, Facebook and Twitter in the context of the elevation, or possible elevation, of any Muslim politician or official.

The idea is to polarise Hindus by portraying the 1946 violence as a conspiracy by the state’s then Muslim leadership, and suggesting that the purported promotion of Muslim politicians and officials by the BJP’s rivals could bring back those disastrous days.

“This attempt to reap political dividends in 2021 from things that happened so many decades ago may or may not work for the BJP. But it certainly carries the risk of reopening old wounds in a Partition-torn region,” said a Calcutta-based historian, unwilling to be named “amid this politico-social volatility”.

He stressed that the 1946 violence had happened largely because of a dubious role played by the British Raj — whose historical wrongs have tended to evoke only silence from the Sangh parivar.

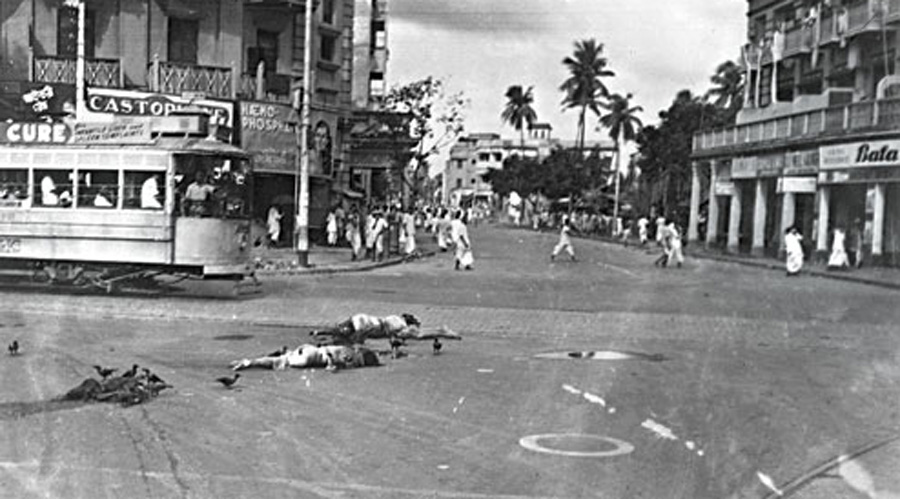

The killings began on August 16, 1946, also known as Direct Action Day, following years of divide-and-rule by the British rulers and an utter administrative failure on the day of the violence.

Direct Action Day was to mark a nationwide protest by Muslims in response to a call by the Muslim League’s Muhammad Ali Jinnah.

The 1946 Cabinet Mission to India, assigned to plan the transfer of power to the Indian leadership, had proposed a three-tier set-up: a centre, groups of provinces, and the provinces separately. In this formation, the so-called groups of provinces were supposed to accommodate the Muslim League’s demand for independent states in Muslim-majority areas.

Initially, both the Muslim League and the Congress accepted the plan. However, Jinnah and his colleagues suspected that the Congress was insincere about it and, in July 1946, the League withdrew its assent to the plan.

Jinnah called for a general strike on August 16 to push the League’s demand for a separate homeland for Indian Muslims.

A series of avoidable and unfortunate events led to large-scale communal violence in Calcutta and elsewhere in the then undivided Bengal. It left at least 4,000 people dead and over 100,000 homeless in the city alone within the first 72 hours.

The much-questioned role of the Muslim League’s Bengal provincial government head, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, is what keeps the saffron camp enthusiastic about this particular chapter of South Asian history.

For months now, the Sangh parivar ecosystem has been issuing an overt, or sometimes implied, message: if a Firhad Hakim can become Calcutta’s mayor or a Pirzada Abbas Siddiqui contest elections today, tomorrow could see a return of the days of Suhrawardy.

“It’s clear what they want to do. They missed their chance to use these things to access power in post-Independence Bengal, despite the wounds being raw then, because of the positive role played by the Congress and the Left in shifting the focus to secular issues,” a city-based political scientist said, requesting anonymity because he works for a central government institution.

“They are betting big on reawakening the public memory of such chapters of Bengal’s history, and using every little development – such as a Hakim becoming Calcutta’s mayor, or a Siddiqui deciding to contest elections — to reignite the majority community’s fears of a possible return to a Suhrawardy-like regime. To the discerning audience, these fears are laughable. But the discerning audience perhaps makes up less than seven lakh among an electorate of seven crore-plus.”

Apart from the social media campaign, small groups of BJP supporters have been raising the subject in informal chats at, say, tea stalls at villages and urban slums.

To the BJP, such a polarisation campaign is a necessity in a state where almost 30 per cent of the voters are minorities, making it imperative for the party to consolidate as much support as it can among the remaining 70 per cent.

A social scientist said that when people receive motivated communication about communal tensions, to most of them it matters little whether the events happened seven days or seven decades ago, or what role the British had played.

She said that only the privileged few with a quality education or progressive upbringing can resist such dog whistling.

“What the saffron IT cell and its bosses seek to gain from this is immediate.

They are not concerned about the consequences or the future,” the academic, who teaches at a top city university, said.

“Their insatiable politico-electoral ambition is fuelling this and the risks are immense. But this Neanderthal myopia was, perhaps, to be expected of them.

“However, if there is a grisly recurrence as a fallout of the BJP’s polarisation politics, there’s no Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi left among us to go on a fast until all sides drop their weapons.”

The social scientist too sought anonymity, citing the political uncertainty.