|

|

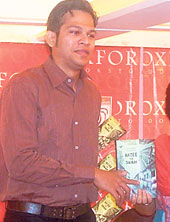

| Chandrahas Choudhury (top) at the launch of Arzee the Dwarf at a city bookstore and (below) a portrait of Rassundari Dasi |

In his very first novel he has an unusual protagonist: a poor, Muslim midget with aspirations the size of the images that his projector throws on the gigantic screen of an old Mumbai theatre.

Chandrahas Choudhury might be a debutant novelist but he speaks with the air of a veteran author. At the launch of his book Arzee the Dwarf, published by Harper Collins at the Oxford Bookstore on July 20 and priced at Rs 325, he was described as “the youngest author that Oxford has hosted”. All of 29 and a literary critic in Observer, Sunday Telegraph, San Francisco Chronicle and Mint, Choudhury, who read excerpts while gesticulating, epitomises the young, Indo-Anglian writer today.

“I selected a midget to tell a story because it allowed me to see Bombay (that’s how Mumbai has been spelt in the novel) through his eyes. When Arzee walks the streets of Bombay, ‘a city of the fives and sixes’, he is looked down upon, but at Noor, the theatre, Arzee looks down on the world from his perch on the projector,” the author explains. Arzee is earnest, suspicious, tender, needy — and his character has the energy and weight to carry the story through 200-odd pages.

With his first novel out on the stands, Choudhury is already on to his second project, an anthology of stories rooted in landscape. “The compilation will attempt to see what geographical location does to humans,” he signs off.

Choudhury is a new name in the world of towering literary greats. Can he, like Arzee, turn it around and secure a vantage point to view the world from a greater height?

This gift of excerpts

This Gift of English, an academic discourse on the teaching of the language in the country, published by Orient Blackswan, priced at Rs 795, was launched at Oxford Bookstore on July 9. The launch was to be followed by a panel discussion with Jasodhara Bagchi, Sujata Sen and Rimi B. Chatterjee interacting with author Alok Mukherjee, who teaches at York University, Toronto.

While it would have been interesting to hear former professor of English at Jadavpur University Jasodhara Bagchi and Rimi B. Chatterjee, who teaches there now, on the subject, most of the evening was taken up by the author reading from his book. Snatches of such readings are meant to arouse reader interest and thus help sell the book. One can only hope that the exercise worked for This Gift of English.

Launching the book, Nabaneeta Dev Sen, who made a hurried exit to attend another function, aptly reminded the audience of how the teaching of English has been undermined in the state. The Left Front government had banned the study of English in the primary classes till recently and this, Dev Sen said, has blighted the future of a generation of learners.

She came first

The first Bengali autobiography is making a comeback, thanks to National Book Trust. Rassundari Dasi’s Amar Jeevan, which was out-of-print, was relaunched recently at a programme in Mahabodhi Society Hall, behind College Square, on her 200th birth anniversary. Editor of the book Baridbaran Ghosh said it was a matter of glory that Bengal’s first autobiography was written by a woman.

“That a 19th century woman who had no formal education was writing an autobiography was a unique example of women’s renaissance,” said former teacher of Bengali at Scottish Church College Alok Roy, who released the book, priced Rs 45.

Rassundari, who got married at the age of 12, conceived 12 times and had to take care of the family as her mother-in-law lost her eyesight soon after her marriage. She learnt to read on her own. The book refers to how she would read the Chaitanya Bhagabat (“gongaiya porite shikhilam”) in the kitchen with her face covered by her sari-end.

“The language is not refined. We have also retained her spellings,” says National Book Trust’s Bengali division editor Bratin Dey. The first edition of the book had come out in 1876, at the initiative of her sons when Rassundari was 67. She appended a section to the book at the age of 87. Her life was later chronicled in Aamaar Thakuma by her grand-daughter Saralabala Sarkar, who was also the niece of Sisir Kumar Ghosh of Amritabazar Patrika.

National Book Trust launched three other books — all works of translation — two days later. One was on the educational philosophy of Japanese educationist Tsunesaburo Machiguchi by Sourin Bhattacharya, while another was a compilation of 26 stories from African literature translated by Agni Roy.

The third, by Rambahal Tewari, was a continuation of NBT’s project of bringing Premchand to Bengali readers, the current selection comprising 13 stories from the master story-teller’s writings for children.