|

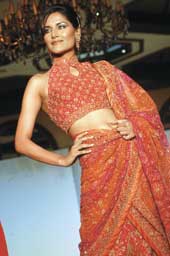

| A model sports a zardosi-embroidered sari by Ritu Kumar. Picture by Rashbehari Das |

Zardosi ? the magnificent metallic embellishment of India ? dates back to ancient times. It finds mention in Vedic literature, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, and all accounts of the Sultanate period. The country, from very early times, was known for the use of gold embroidery on a variety of objects including furnishings, trappings, parasols, and equestrian ornaments. The more aesthetic and evolved embroideries were used on court costumes and especially on accessories such as shoes.

The historical accounts of this craft are shrouded in the usual romantic stories and inaccurate data. But the only certainty is that zarkas ? a Persian word meaning zari or gold embroidery ? was widely used in all the accounts. History says that from the 13th century, the craftspeople who worked with this medium, setting seed pearls and precious stones with use of fine gold and silver wire, were known as the zardos workers.

In the course of my studies I found a little nugget, a legend popular with the zardosi workers of Delhi that relates to the origin of this craft. Strangely enough, it was an account of a shoe, especially embroidered in gold and silver, which was used to hit the reigning king on the head as it was believed to cure a specific brain malady.

Of all the crafts of the country, the zardosi seems to have flourished and survived to the present day like none other.

My first encounter with the zardosi craftsmen was in 1972 in Calcutta. I had begun work on revival of patterns of old hand blocks. And, while studying miniature paintings of Akbar?s period, I got an insight into the sophistication of the colour palette and delicacy of embroidery and motifs used on the costumes of the royalty of that time. I was in search of a costume or a swatch of work of the 15th or 16th century, when it was said that the craft was at its peak. I was curious to experiment with the embroidery and the use of thread and gold. It turned into a futile exercise, as at that time there was no reference either in a museum or library, which could have been enlightening.

Walking around Calcutta?s New Market, the Marwari area of Burra Bazaar, or Chandni Chowk near Red Fort in old Delhi, looking for the embroideries, brought home to me the fact that we had lost yet another vocabulary. There was some highly skilled workmanship available, but the base fabrics, the plastic replacements of pure gold and the motifs were so far removed from the original, that the product did not resemble what had at one time bedazzled visitors to the royal courts of India.

Then one day, two young zardosi craftsmen walked into my studio. They had heard that I was making enquiries about the embroideries. I inducted them into the development programme of our attempt to revive an old aesthetic.

In the marketplace, tinsel had replaced gold. As a substitute, we used plastic-drawn wire wrapped in cotton thread, to dull the tawdriness of lure, and thus, sought to recreate the burnished look, which with its depth of richness and beauty had transcended time. Material was dyed, thread was sourced, and swatch after swatch of beautifully embroidered textiles was created, matching miniatures and reference materials. I could not help being impressed by the high degree of skill that our zardos craftsmen still possessed.

As a commercial proposition, they were keen to complete pieces in their own villages. Curious to visit these areas, I made trips to Bengal?s districts, old Delhi, Farukhabad and Lucknow. In these areas survive the zardosi workers who practice their crafts in their huts. An image far removed, as one conceives it, from Mughal India and its formal karkhanas (court workshops), where the craft reached its zenith.

During the last 50 years, the revival of zardosi has been phenomenal. Not only did it find its way into designer outlets, but is being used yet again for interiors of mega weddings, in and out of Bollywood. Today the Indian ramp is ablaze with alternatives that the craftspeople work with ? the materials may not have the same aesthetic of the Mughals, but are catering to the demand of highly-ornamented garments with glittering beads and sequins.

If you happen to spot a slinky sequinned gown at an Oscar award ceremony, designed by John Galliano or Georgio Armani, chances are that the workmanship is of Indian origin. With the change in times and demand, the zardosi craftsman is vital to the garments ?en vogue? in Hollywood and Bollywood.

The richness of gold may no longer grace the work of zardosi craftsman, but the glitter and glamour endures, hopefully, for all years to come. Zardosi is as tenacious as the wires the craftsmen work with.