Calcutta may have been an “absent presence” in her life but on Thursday Jhumpa Lahiri was a powerful presence at Victoria Memorial Hall, speaking at a “prologue” session of the Kolkata Literary Meet, held in association with The Telegraph. Sitting before a 600-strong audience, the Pulitzer Prize-winning Bengali-American author spoke to Rudrangshu Mukherjee of The Telegraph. Excerpts.

|

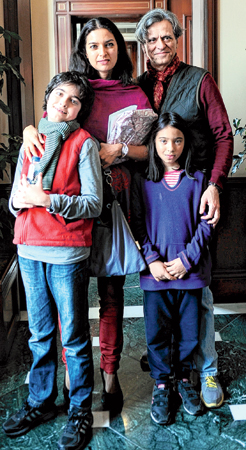

| Jhumpa with husband Alberto Vourvoulias and their children Noor and Octavio |

The absent presence

Calcutta has been an absent presence in my life and occasionally it was a present presence, when we would come, but the majority of my conscious life and my upbringing was shaped by and informed by the absence of this city and what that absence meant to my parents.

Calcutta was always there but it was also not there and so I think that tension, that contradiction in terms is something that’s very much in my blood and all of my writing until now certainly has come out of that trying to understand how and why a place can have such a powerful hold on people. And I think that fascinates me particularly because I personally don’t feel any connection like that.

I don’t have any singular connection to one place or one country. I don’t feel like I come from any specific place. But I was raised by two people who not only do come from a specific place but keenly felt the absence of that place as they were raising me. So I think it was inevitable that that would begin to inspire my writing.

I was raised in a sort of double world, raised in the United States for the most part but always going back and being aware of the coming and the going, the back and forth.

I was raised with this sort of double-layered yearning — my parents’ yearning for Calcutta, which I didn’t share but which I experienced...

A strange yearning

And then there was my own longing for a sense of belonging anywhere. But I never found that place. It troubled me, very much, when I was a child. It was a source of constant anxiety that I didn’t come from any particular place, that there was no place that I could go and identify myself completely with.

It bothers me much less now. Now I think of it as a certain freedom, from the longing. But that doesn’t mean that now and then I don’t have a sort of strange yearning for belonging in any place.

Now I live in Rome, in Italy, which is a country in some sense similar to India. It is a very old country and families tend to stay together in the cities and town they come from and now I have many friends there and they can go back to their family tree generation upon generation upon generation and feel a deep-rooted connection to their country.

|

| Jhumpa with parents Amar and Tapati Lahiri. Pictures by Rashbehari Das |

Desh for them

I know that I too have a family tree here but I think the feeling of belonging is much more of a psychological feeling, it’s not really connected to reality. And I know that because my parents have lived outside of Calcutta for almost half a century but they still feel that in some sense they belong here. When they come back here, they’re coming home. And they still refer to it as desh and that’s what it is for them.

At home in a library

I felt that something was missing from my life for much of my life and I think things began to change when I started writing. Because I felt for the first time whole as a person and I thought of myself as coming from other writers who had inspired me and guided me and that gave me a sense of belonging.

There were certain places I felt I belonged to regardless. I always feel at home in a library, for example. Whether it’s in Calcutta, or Rome or Rhode Island or wherever… libraries to me always represent a kind of home.

As I got older, as I began writing, it bothered me less and less that I don’t have any one country to call my own.

I was born with an Indian passport, I was appended to my mother’s passport. Then I became a naturalised US citizen. Then I got my UK passport because I was born in London and so in my life I have actually possessed three passports. To be honest with you, none of them means anything to me. They just let me get on and off the airplane.

The idea of being connected to literature was very reassuring because I felt that literature was a place, at least in the world of pre-existing books and authors, there’s a sort of magical confederation that one feels. So that I can feel an intense connection with a writer like Thomas Hardy, I mean I obviously never knew him personally, and I don’t know what he would have thought of me if we ever did meet, but it’s completely irrelevant because the connection is through the writing... not only among writers but among readers and writers. Nothing but the words are relevant.

|

| Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay hands over the first copy of the Bengali translation of Jhumpa Lahiri’s latest novel, The Lowland, to the author at The Oberoi Grand on Thursday morning. Titled Nabaal Jomi and published by Ananda Publishers, the translation has been done by Paulami Sengupta |

My influences

I started reading in English and so naturally the vast majority of my literary influences are Anglophone writers.

I was a passionate reader as a child. I felt much more connected to literature than to actual social interaction and in retrospect, I think that makes sense.... I felt that books were my companions and the first friendships I formed were around the idea of writing and reading together.

It’s impossible to list all the authors who have influenced me. I can say for The Lowland one of the authors I feel heavily indebted to is Thomas Hardy, whose novels I deeply admire and I read and reread a number of them during the period of working on this book…

For short stories I read Chekov, Alice Munro, William Trevor, Mavis Gallant… I am very aware that 99.9 per cent of my literary influences and inspirations are people who write in English and tend to be American or English writers and some literature in translation.

But on the other hand, I was always leading my emotional life until quite late in Bengali. I was always aware that the language that I was reading in was a foreign language to my parents and that the books that gave me pleasure were books my parents had never even heard of.

I would come here and people would give me Thakurmar Jhuli and kobita and everything and so I would see there was a whole other tradition that had nourished them and everyone here. I had only a bit of it because I can’t really read very easily, it was always something more oral.

My two anchors

Just the work of writing, the being alone, the thinking, the meditating on characters, their dilemmas, their day-to-day lives, this has given my life a sense of purpose that I didn’t have before. And now I am also a mother, I am raising two children. So I have my writing and I have my children and I feel like these are my two anchors.

The outsider

Both The Real Durwan and The Treatment of Bibi Haldar [in Interpreter of Maladies] grew out of a building where my mother was raised in north Calcutta. No. 110 Vivekananda Road. That’s my mamar bari....

I spent a lot of time in this building and both those characters, Boori Ma and Bibi Haldar, grew out of observing two people who lived in some sense in that building and I saw how they were perceived by the people who lived in the building — a certain amount of both compassion and tolerance but there was also a barrier…. I must have felt a connection with them because I too felt like an outsider in Calcutta. And I was. I was acutely aware that I was a foreign import... people regarded me as something from outside.

‘Do you speak Bengali, do you eat fish, do you know how to take the bones out’ and all of these questions… clearly it was hard for me to feel like one of my cousins here, who didn’t get asked those questions.

The outsider’s experience is my experience. I felt like an outsider in America, I felt like an outsider here, now I live in Rome where I feel like an outsider of a different kind there. And now I am used to it. I accept it. Mavis Gallant’s title Varieties of Exile absolutely encapsulates my experience of life on this earth.

The Lowland

It had a very personal origin, this book. My father’s side of the family is from Tollygunge and I would spend a lot of time in this house where my paternal grandparents lived.... I learnt about an execution that had taken place during the crackdown in the early ’70s and it had happened just a stone’s throw from the house that my father was raised in. I was very haunted by this information.

I think the reason it had such an emotional impact on me is because I could sort of picture it, I knew the neighbourhood, I knew the house, I didn’t know the people, the family or the victim….

The image that haunted me the most was the confluence of the violence and the family gathered and how that must have impacted everybody involved. Most of my stories till now have been family stories but I think the reason it has this particular political historical background is that I learnt about this and I simply wanted to know why it had happened and that led me on this journey, trying to educate myself about the period.

|

Ashima or Bela

Anirban Bhattacharya, who said he was doing a Phd on the author, wanted to know whether Jhumpa Lahiri today was more in tune with Ashima of The Namesake or Bela of The Lowland.

Neither. They are who they are. I mean Bela, I suppose, biographically shares a little bit more of my life in that she’s born outside of India and is born to Bengali parents who live in America. That’s about it. She’s a very different person from me.

Ashima is someone much more modelled after my mother and versions of my mother. The inspiration for Ashima’s character came from all of my “other” aunts. I grew up with no extended family in America but my parents created an alternate extended family in America so I have my mashis there and her character was taken from those women.

I was really impressed. It was a moving experience. She is a thoughtful, intense person who thinks carefully about the process of writing.

Supriya Chaudhuri, academician

It’s a coincidence that I started reading The Lowland a few weeks back. I especially like the sensitivity in her writing. The session was very interesting. It was fascinating to discover a bit about the mind behind a particular work of literature.

Anik Datta, filmmaker

I have read three of her books and I think she is superb. The Lowland is amazing. I would love to know what significance Bengal had on her as a child, what is it about this place that makes her portray the interplay between cities like Boston and Calcutta so beautifully!

Albert Lobe,

Co-director, MCC India

I read The Namesake. I have just started on The Lowland. The interest she has been able to generate is lovely! I feel proud to see so many people here, it’s really nice to know Calcutta is so culturally aware.

Sharbari Datta, fashion designer

Reading her short stories and novels was one thing and hearing her speak was something else. Now I can clearly see her mindset, the way she thought, the way she placed her characters and the connections in each story.

Upasana Chakraborty, 2nd year, Jadavpur University