|

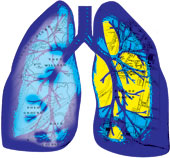

What are the chances of being knocked down by a motorcycle or even a car in the middle of the Brigade Parade Ground? And what are the chances of your blood rushing to your head as you hear Tunir maa, a Sylheti chartbuster, blaring from the shiny mobile phone of a yob killing time in what was once dubbed the “lungs of the city”? Alarmingly high, I would say, and those who regularly visit the city’s last great open space for long walks or for a game of football or impromptu cricket would promptly agree with me.

Hordes of young men on motorcycles leaving dust devils in their wake invade the Maidan every morning, and so do fleets of cars at all hours, ignoring “No parking” and “Towing zone” signs along Red Road. The treacherous and undulating pavements of central Calcutta dotted with pitfalls have turned into freeways for motorcycle, extensions of shops, parking lots and open-air toilets. Lawlessness prevails on the narrow streets, where cycle vans and diesel-fume belching three-wheelers demand right of passage. One should not be surprised if the same fate befalls the Maidan.

Mounted police officers may cry themselves hoarse claiming that 20 to 25 of them are on duty for two hours from 6am, but they are never to be seen in the Brigade Parade Ground on any given day, save during football and cricket matches. Headlights can be seen criss-crossing across the bare ground even quite late at night. The only equine creatures that trot across the ground are skeletal ponies tied next to the Fountain of Joy (anything but joyous) opposite Victoria Memorial Hall.

Burning nostrils

Long before the heat of the sun chases it away, a mist hangs over the grounds anchored by the clumps of trees and the Angel of Victory on top of the Victoria Memorial Hall dome. Many of its fine trees were blown down in the cyclone of 1864. In the following century, many were felled during the Metro Rail construction, and the Aila, too, left behind a trail of destruction. The skyline of jagged highrise buildings and the trees look as if both the British artists Turner and Gainsborough had collaborated on painting this phantom vista, but if you take a deep breath your burning nostrils will tell you that this is no mist but a miasma laden with exhaust fumes and dust trapped by moisture.

Hundreds of roadside eateries in the Esplanade area, dotting Chowringhee and the Sahid Minar bus terminus are still dependent on chulhas that are lit early in the morning and this does not help matters. Sweepers burn piles of dry leaves and garbage all around Curzon Park, over and above the tyres and electric wires that turn into home fires for vagrants. The Calcutta Municipal Corporation (CMC) had once declared coal-fired ovens and burning of garbage illegal, but like most rules laid down by the administration, this one too is more observed in its breach. Yet in spring, the palash trees burst into flames and even the odour of human and animal waste cannot overpower the vernal perfume of mango blossoms.

In the first decade of the 20th century, H.E.A. Cotton wrote: “…the Maidan still constitute the chief glory of Calcutta.” The Maidan and Fort William are located on the spot where once stood Gobindapur, one of the three villages — the two others being Kalikata and Sutanuti — that formed the nucleus of the modern city of Calcutta. The area was cleared of its “tiger-haunted” jungles after 1757 to build this new fort. The Maidan is in the custody of the army (the ministry of defence).

Calcutta’s “barefoot historian” P.T. Nair says perhaps the army is unaware that the Fort William Act, 1881, was never repealed. “Legally there is no Maidan and whatever the army says is final,” he says. In accordance with Section 2, Act XIII of 1881 (The Fort William Act, 1881), “the governor-general in council hereby notifies that, for the purpose of the said Act, the limit of Fort William in Bengal is the line of the ‘crest of the glacis’.”

This empowers every police officer, non-commissioned officer or military policeman to arrest without warrant any person who within his view commits any of the following offences: making excavation in unauthorised places, rash or negligent driving, destroying trees, creating a disturbance.

Black Sunday

Unnumbered feet tread the Brigade Parade Ground every day, and when political parties choose to hold meetings there, a sea of humanity swamps it. The aftermath is there for everybody to see. This spot remains scarred and pitted throughout the year, as holes are dug to erect daises and quick meals are cooked for the masses.

The Maidan has a long history of public meetings and exhibitions. The grand Calcutta International Exhibition had opened opposite the Indian Museum in 1883. The annual Book Fair came years later. In 1911, King George V was entertained here. On April 6, 1919, called Black Sunday, a protest meeting was held against the Rowlatt Act before what is known as the Sahid Minar today. Chittaranjan Das was among the eminent speakers.

That was perhaps one of the first political meetings to be held here. The biggest crowd-puller was the meeting where Khrushchev and Bulganin shared the dais with Nehru, Bidhan Chandra Roy and Ajay Ghosh, the leader of the undivided Communist Party, on November 29, 1955. But times have changed since and environmental concerns must be addressed, even if the government is unwilling to take any positive action to arrest the Maidan’s degradation.

The 1,400-acre Maidan is bounded in the north by Esplanade and Raj Bhavan, on the south by AJC Bose Road and Hastings, on the east by Jawaharlal Nehru Road and on the west by the Hooghly and most of the ground is mangy. Vast areas opposite the Eden Gardens and behind the famous sports clubs are bald and serve as garbage dumps. But the field within the walled extension of Fort William along Casuarina Avenue visible from outside is manicured.

Large swathes of the Chowringhee side, like the sections adjacent to the fort, have turned into wildernesses of weed and scrub. The tank behind the Jawaharlal Nehru statue is a hamam for the homeless. Curzon Park (renamed Bhasha Udyan), where the state government had once planned to construct a mall and car parking space, is a jungle of filth, briars and weeds. Encircled by iron fencing, its gate is embellished with the likeness of performing bauls. This look is in keeping with the monstrous pink “lotus” fountains, one each at the Chowringhee-Dharamtala corner and the Red Road crossing to keep Lenin and Netaji company, respectively.

Statue shocker

Patriotism made us blind to ugliness when unsightly statues of nationalist leaders were foisted on the Maidan area in the 1960s. The pedestal with a huge bathtub-like flower pot in front of Prinsep Ghat originally had the magnificent statue of Napier of Magdalla on it. After it was shifted to Barrackpore the pedestal lay bare for many years. Then the PWD took upon itself the task of “beautifying” the area around 1997 and the “bathtub” was installed.

The tram ride alongside the Brigade Parade Ground and the race course leading up to Kidderpore is one of the most exciting anywhere, particularly during the monsoon when it turns into an emerald carpet with scattered pools of water mirroring the sky and the Victoria Memorial Hall dome.

At other times the Maidan is bone dry. A dirt track beginning from the spot where the Maidan tent of the Royal Calcutta Golf Club stands and terminating at the point where the Fountain of Joy is laid out wends its way through the heart of this plain. Its last half is tarred. Earlier, political meetings were held at the foot of what was once called the Ochterlony Monument. Now the dais is erected cheek-by-jowl with the fountain.

It is easy to avoid stepping on the equine and canine droppings and the pellets left behind by the grazing goats, but almost the entire area is skinned over with small plastic packets of pan masala. The PWD is partially responsible for the Maidan’s upkeep, but given our callousness, it is impossible for any human agency to keep the place clean on its own.

Law alone cannot save the Maidan. Shivaji Park in Mumbai is primarily used by local residents as a recreational space and for sports activities. But political parties do not spare this one either. Mumbaikars hope that political rallies will stop once the new heritage listing (where a Grade 1 status is recommended as with the Oval maidan in Mumbai) is legislated. Without some such drastic measure, the Maidan, too, cannot be saved from the marauders.

What measures are most necessary for the Maidan? Tell ttmetro@abpmail.com